Spotlight on dark happenings

I fear that I have something of a blindspot as regards child abuse. So anyone reading this who was abused as a child has all my sympathies, but may want to stop reading now. I spent nearly seven years at an English single-sex, boarding school in the 1950s and the 1960s, and I am very grateful that I was never the object of unwanted same sex advances. We were all aware that some masters were [almost certainly] ‘queer’; the word ‘gay’ had not yet been appropriated. And it was often said that at school choir camp [I was regarded as an unteachable non-singer] the trebles ‘smoked like chimneys, drank like fishes, and went to bed with the tenors and basses’. But I don’t ever remember hearing the words ‘paedophile’ or ‘child abuse’. In more recent times the world has moved on, and more than one former master from my old school is now behind bars for sexual offences. Including, sadly, a former school chaplain.

Sitting on a plane somewhere a few years ago I watched the American film Spotlight, and I have just been reading the book of the same name which was reissued to coincide with the launch of the film in 2015. Both book and film are based on a substantial report published by the Boston Globe in January 2002. The report was written by their investigative team, and it showed that hundreds of children in the Boston area had been sexually abused by Catholic priests. Shockingly the report also showed that the Catholic hierarchy had known what was going on in many cases. Instead of protecting the community that it was meant to serve, the Church exploited its powerful influence to protect the institution from scandal. Offending priests were referred to psychiatric units for counselling and ‘therapy’, and were then transferred to other unsuspecting parishes. Where the priests continued to prey on and abuse new groups of children.

It is a messy subject. Unfortunately it is also a messy book. There are a lot of tragic cases. Deviant priests made a bee-line for needy children; often boys whose parents or single parents were already struggling to cope with big families. But the timeline of the book is confusing. Many of the stories are very similar, and the ‘present’ moves between the 2002 report and the 2015 re-issue. And the narrative moves between the Archdiocese of Boston and similar cases in other Dioceses.

Two things strike me. One is simply the scale of the abuse. John J. Geoghan, known to his parishioners as ‘Father Jack’, was shunted between half a dozen parishes in Greater Boston over three decades. But an archdiocesan official had already labeled him as an incurable child molester, “a pedophile, a liar, and a manipulator”. By the time the report was published in 2002 more than 150 people had come forward with horrific childhood tales about how Geoghan had fondled or raped them. [Geoghan was eventually de-frocked by Pope John Paul II in 1998, and was sentenced to ten years imprisonment in 2002 for indecent assault and battery. In 2003 he was strangled by his cellmate, Joseph Druce, allegedly himself the victim of child abuse.]

The second shocking aspect is the lengths to which the Catholic hierarchy went to in order to cover up the abuse. Initially the Roman Catholic church sought to argue that serial predators like Geoghan and James Porter [of the Diocese of Fall River, Massachusetts] were simply ‘rotten apples’ and isolated cases. But in January 2002 the Boston Globe revealed that the Archdiocese of Boston had already secretly settled sexual abuse claims against more than seventy priests over the past decade.”What they were protecting”, said one abusive priest, “was their notion that the Church is a perfect society. If the Archdiocese had really wanted to protect its other priests from the scandal, they would have gotten those of us who abused children out of there much faster.”

It is difficult to distinguish between the culture of secrecy and deliberate deception.Thus Cardinal Bernard Law, already Archbishop of Boston for more than a decade,, wrote to Geoghan in 1996: “Yours has been an effective life of ministry, sadly impaired by illness … I would like to thank you … The passion we share can indeed seem unbearable and unrelenting … We are our best selves when we respond in honesty and trust. God bless you Jack”.

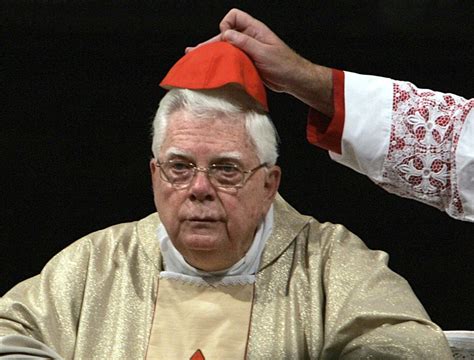

In April 2002, following the Boston Globe‘s public exposure of the cover up by Cardinal Law [and his predecessor Cardinal Medeiros] of scores of pedophile priests in the Boston Archdiocese, Law promptly committed himself to staying on as archbishop and addressing the scandal. But after a letter urging Law’s resignation had been signed by 58 priests, mostly diocesan priests who had sworn obedience to him as their superior, Law submitted his resignation as Archbishop of Boston to the Vatican, which Pope John Paul II accepted in December 2002. The Boston Globe said in an editorial the day after Law’s resignation was accepted that “Law had become the central figure in a scandal of criminal abuse, denial, payoff, and cover-up that resonates around the world” Within weeks of his resignation Law moved from Boston to Rome, where he was appointed Archpriest of the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, a sinecure with only ceremonial duties. Some saw this an attempt to shield Law from potential criminal prosecution as his new position conveyed citizenship in Vatican City. He eventually died in Rome in December 2017 aged 86.

Personal vignettes

I don’t remember any mention of child abuse when I trained at Wycliffe Hall in the 1980s. When I went to a parish in the Scottish Borders in 1990, no-one bothered to tell me that the old man across the road who was a regular member of the congregation and who was frequently around the churchyard had been formally cautioned by the police for inappropriate behaviour with young children. [But no-one told me either about the man who liked to count the collection so he could filch some of it to spend in the pub.] One morning in the 1990s a young lad in the congregation arrived at The Rectory in tears; he was an assistant leader in the Air Training Corps and had been the object of an accusation of abuse of the cadets. At which point a Group Captain had come down from Edinburgh to do some insensitive questioning in the community. It was clearly malicious. I rang the Detective Sergeant in Galashiels who was conducting the enquiry to tell him who had most likely written the letter [I was right, and the accuser was subsequently brought to court, and found guilty]. The detective almost thanked me, and we agreed that the conversation had never taken place.

Two decades later Child Protection, now generally known as Safeguarding, is a significant part of church life. In the [really quite small] Scottish Episcopal Church, the church website says that there are three full-time safeguarding officials, supported by seven Diocesan Protection Officers, several local co-ordinators, and the members of the Provincial Committee for the Protection of Children and Vulnerable Adults. This level of regulation is a response to the Children’s Act of 1989, legislation which reflects the United Nations Convention [UNCRC] of the same year. As an elderly dinosaur, I sometimes think that legal frameworks are no substitute for knowing and trusting members of the local community. And I sometimes think that at least a part of the significant cost of implementing the current Safeguarding policies could be better spent on training Sunday School teachers and youth-workers. But I acknowledge that this is just a reactionary blast from the past.

More positively I am hugely impressed by the energies and creativity of a new generation of children’s workers and youth workers. Such as the husband-and-wife couple who work at the New Frontiers Church in High Wycombe which my daughter and son-in-law and grand-children attend. And again the couple who lead Family Worship at Holy Trinity, Brussels.

How can these things happen ?

How do we begin to understand what happened in the Boston Archdiocese ? There is no shortage of books about the incidence of sexual abuse by priests. But there does seem to be a shortage of reliable data. Are priests worse than any other profession in which adults work with children ? Teachers, for example. And why does this seem to be a problem that has predominantly plagued the Roman Catholic Church and not other denominations ? One obvious answer is celibacy. Although celibacy was valued from the early days of Christianity, and was first mandated in the fourth century, it was widely enforced only from the twelfth century. Defenders of celibacy describe it as a gift, a charism, a witness to sanctity. Though critics have suggested celibacy was enforced largely to prevent Church property from being passed from a priest to his children. Whatever its origins it seems clear that an all-male, celibate priesthood attracted men who were uncomfortable with their own sexuality. They responded by cutting off a part of themselves [metaphorically, not physically].And some of them then acted out their sexual maldevelopment in inappropriate ways.

If the imposition of celibacy was a major contributory factor, the problem was made far worse by a culture of secrecy and of clericalism, the notion that the clergy were a race apart. Priests were thought to be ontologically different from other [lesser] people. And therefore not subject to the same rules and regulations. [A bit like some government ministers during the current COVID-19 lock-down. Only worse !] Not only did shame and embarrassment, and threats by their abusers, keep many victims from disclosing their abuse. But their families, often from a working class background and brought up with a deference culture, found it almost impossible to confront the parish priest, often himself a family friend. [Clericalism sadly is not limited to the Roman Catholic Church. CS Lewis once said, I think, that the Devil’s greatest achievement was to divide the church into two groups of people, clergy and laity, who neither liked nor understood each other. It was Will Storrar, a Church of Scotland minister now teaching at Princeton, who said: “The Church of Scotland are meant to worship God in Jesus Christ, but too often they worship the minister in the pulpit”.] The great danger of that clerical culture, and the high view of priesthood that goes with it, is that church leaders can easily be persuaded that the reputation of the institution is more important than the lives of individual men and women.

So, my copy of Spotlight is joining a growing pile of books that are going to the charity shop. And I am going to read something that may well be more wholesome about the Scottish Episcopal Church in the nineteenth century. And anyone who happens to read these reflections is very welcome to tell me where I am going wrong.

May 2020

Thanks for this – i too went to a single sex school and was “pashed” on an older girl for a couple of years, and then had some of the younger ones “pashed” on me! it is all very strange that not just the RC but the Anglican church has been implicated in some of this. I agree that knowing your people and young ones is much better than reams of safeguarding! I had to do the online course as a Diocesan synod member – useless!

Many good wishes to you both and we are fine here if rather frustrated!

Love Madge

LikeLike

Thanks, Madge. I’ve no idea what happened in all girls’ schools. I never spoke to a girl until I was thirty-three ! [That’s my story.] Glorious weather here. And I am very grateful for a garden and plenty of books. Pretty confusing messages from down there from blustering Boris.

LikeLike

Food for thought. Last year a film, ‘Grâce à Dieu, was released in France about the case of a RC parish priest at Ste-Foy-lès-Lyon. He has now been convinced and sentenced. The film is based on victims’ testimonies. It is disturbing in a right way as you start thinking. The case has caused a lot of rippled – upto the diocesan bishop resigning from office.

As usual a very good read.

LikeLike

Thanks, Armand. I’ve not seen the film, and I don’t know the whole story. What I thought I understood was that Cardinal Barbarin had been put on trial for not managing the case better, i.e. not reporting the priest in question to the civil authorities; and that the abuser himself had not yet been brought to court.I do have some sympathy for Philippe, as it seems to me that people are being judged by today’s standards for something that happened a few years back. Something very similar happened here in the UK. A recent tv programme was severely critical of Archbishop George Carey for not taking [today’s] proper action with regard to Bishop Peter Ball, a persuasive and persistent child abuser.Am I right in thinking that Philippe has now been allowed to resign as [Arch]Bishop of Lyon ?

LikeLike

Reviewing replies. Barbarin was celebrating his last mass as the official bishop of Lyon this morning. He has been given a chaplaincy (aumônier) somewhere in Brittany.

The perpetrator was convicted and sentenced. Barbarin was judged for not bringing him to justice but merely displacing him to an other part of the diocese – nowhere else than my home church.

Plus the cardinal had been very clumsy in handling the situation – and even worse the media- when it all came out. He was sentenced in first instance and then cleared by an appeal court. But he had decided to step down.

LikeLike

As I probably said before, I feel quite sorry for Philippe Barbarin. I guess he did what most bishops used to do; kept the case quiet, didn’t tell the police, and moved the abuser on to another post. Which seems wrong now. But which used [I think] to be the norm. Here in the UK I see that George Carey has had his PTO [Pernission to Officiate] for the Oxford Diocese withdrawn [for the second time] because of his [mis]handling of past abuse cases in the C of E.

LikeLike