Anti-Fascism in the English Public Schools 1933-’39

“ Often enough the public school system is attacked from the outside, but it is surely remarkable to find a boy of fifteen launching a critical magazine to mend the faults of his own and other schools … It will, I am assured, openly champion the forces of progress against the forces of reaction on every front, from compulsory military training to propagandist teaching.”

These insignificant paragraphs, which appeared in the Daily Telegraph on January 26th, 1934, gave little warning of the impact that Esmond Romilly, the boy reformer, was to make not only on the lives of numerous headmasters but also on the pages of the national press in the coming months.

Esmond Romilly was a chubby schoolboy with dirty finger-nails. He might be seen as one more in a long line of ex-public school iconoclasts. But his criticism was not confined to the public schools. Which he loathed on the grounds that “their admitted object is to provide a new generation of empire-builders (or rather empire-savers)”. His attack on the reactionary forces that permeated these schools was allied with propaganda for left wing political beliefs; and it was these that brought him into disrepute. In the first issue of Out of Bounds, in March 1934, Esmond wrote:

“The editors of Out of Bounds make no attempt to disclaim their political convictions. They believe that … nearly every one of the things they are fighting for is there because of the position the Public Schools hold within the framework of the capitalist state. Consequently they are vehemently opposed to a more vigorous offensive of capitalism under the emblem of the Fasces.”

Romilly was an energetic rebel, a nephew of Clementine Churchill, who had run away from his school Wellington to live over a bookshop in Parton Street, Bloomsbury from where he edited the magazine. He and his brother Giles were not alone in their views. The Daily Mail published a hysterical article entitled Red Menace in the Public Schools.. The first issue of Out of Bounds contained reports from nineteen schools, including Eton where over a hundred copies were sold. The number of schools contributing grew steadily; with grievances expressed about compulsory military training and about the suppression of political opinion “of a dangerous nature”. The correspondent at Aldenham was threatened with expulsion, and Out of Bounds came to be banned there, as it was at Cheltenham, Uppingham, the Imperial Service College, and Wellington.

Writing the essay

Why was I interested in all this stuff in 1963 ? Partly because, with time to spare between A levels and Oxbridge entrance exams, I was working towards a Trevelyan Scholarship. As a History Grecian at CH, I had written a very long [and probably confused] essay about political thinking in England in the 1930s. About the appeal to different groups of Fascism and of Communism. And Michael Cherniavsky, my history teacher, suggested that I should try and build on this. Partly too because I shared many of these questions about the culture of English public schools, including my own. If ‘fascist’ is thought inappropriate, and it has subsequently become an overused term of abuse, ‘bolshy’ was in common use in my school days. Used, especially by my housemaster, as a pejorative epithet to describe anyone who questioned authority or expressed mildly left-wing views.

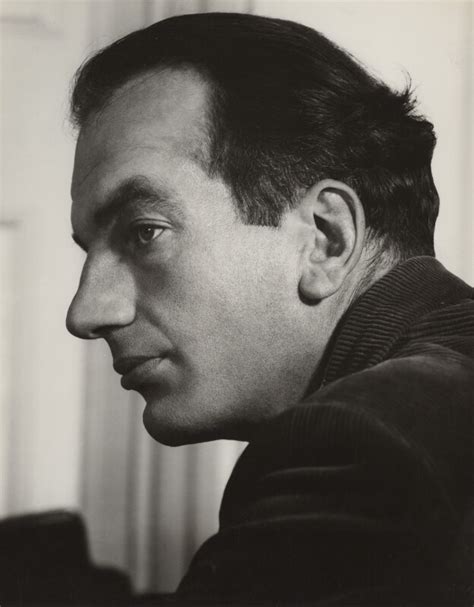

Michael Cherniavsky

Michael was, I suppose, an unusual teacher, at CH or anywhere else. He was a white Russian, born in 1920 in Buenos Aires, Argentina. His father was the celebrated Ukrainian Jewish cellist, Mischel Cherniavsky, whose trio had played before Tsar Nicholas II of Russia. His mother was the daughter of a Canadian sugar baron from Vancouver. Michael was educated at Westminster School, and was then Brackenbury scholar at Balliol. He taught history at Christ’s Hospital from 1948-66, more specifically English and European medieval history; and then moved to become Professor of History at the University of Waterloo, Ontario, from 1967-83. During his years at CH, Michael’s pupils won a stream of awards at Oxford. His years in Canada were arguably less successful. Later Michael retired back to the UK, to Horsham; and his ashes are scattered Christ’s Hospital.

As one of Michael’s pupils I benefitted enormously from his teaching. And I no doubt acquired some of his prejudices; a love of books; an enthusiasm for Europe, and for France in particular; a sceptical attitude towards most forms of authority. In his time at Westminster, Michael had been a founder member of the United Front of Progressive Forces. Known to its contemporaries as UffPuff ! It was a broad-based coalition of anti-fascist pupils; the chairman was a Communist, while Michael as secretary of the group was a Liberal-Pacifist. Which probably helps to explain why he nudged me in the direction of my [modest enough] research.

Anti-Fascism in the English Public Schools, 1933-’39

So I spent quite a big chunk of 1963 doing more reading about the 1930s. [As I write that sentence I am amazed that there was only a thirty-year time lag between the events and my schooldays.] I had already read Julian Symons book on The Thirties, and Colin Cross on The Fascists in Britain. Now I was delighted to secure a ticket for the Reading Room at the British Museum, where I read all four issues of Out of Bounds, the magazine that had so excited the Daily Mail. And I also read the book of the same name co-authored by Esmond Romilly and his brother Giles.

The anti-fascist movement in the public schools was most obviously opposed to Oswald Mosley and the nascent British Union of Fascists. In a letter to me, Cosmo Rodewald wrote:

“… what he [John Cornford] and I felt impelled to rebel against was the established economic, political, and social order in this country; an order characterised by mounting unemployment; an order which seemed destined to increase the misery of the working classes, as Marx had predicted, in spite of the oppression of the colonial peoples as a source of wealth; an order which was nevertheless so powerful that labour reformism could achieve nothing substantial against it; an order which existing internationally had caused one world war and would probably cause another; an order which the public schools existed to train each new generation to perpetuate.”

In June 1934 Esmond Romilly attended the British Union of Fascists mass rally at Olympia, along with Philip Toynbee, who had just run away from Rugby to join him. Toynbee recalled that they made a preliminary visit to a Drury Lane ironmonger to equip themselves with knuckle-dusters. Both were ejected forcibly, but the visit was described at length in the second issue of Out of Bounds.

Fascism meant not only Mosley and the home-grown variety but equally Mussolini in Italy and Hitler’s National Socialism in Germany. The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936 made many boys more politically conscious. Christ’s Hospital as a whole during the thirties took little interest in party politics and Out of Bounds did not circulate there. But John Morpurgo recalled:

“… for my own generation which was a little later, I would say it was never much excited by party politics. There was a fairly substantial leftishness, especially among History Grecians, but it came out as an interest in the cultural avant-garde more than it ever did in political activity … …

But the one political experience which really aroused us was the Spanish Civil War. We were all without exception pro-Government.”

Many of the anti-Fascists were demonstrating as much against features of the public school tradition as they were against Mosley, Hitler, and Mussolini. In the Michaelmas term 1934 Sedbergh held a debate with the motion ‘This house deplores the basis of Fascism on which the Public School system is founded’. WH Auden, commenting on the ‘honour system’ at his own school, Gresham’s, Holt, wrote that: “The best reason I have for opposing Fascism is that at school I lived in a Fascist state.” In his book Godliness and Good Learning, David Newsome suggested that these aspects of school tradition were really the remnants of the late Victorian cult of Godliness and Manliness:

“These three men – Kingsley, Hughes, and Leslie Stephen – were none of them schoolmasters. Yet, if we put together the various ideals which they upheld in their writings … the result is this: the duty of patriotism; the moral and physical beauty of athleticism; the cultivation of all that is masculine, and the expulsion of all that is effeminate, un-English, and excessively intellectual. Thirty or forty years later the same ideals or something very like them might be taken to be the creed of the typical housemaster of the typical pubic school.”

I enjoyed working through all this stuff. In addition to reading whatever books I could find, I was pleased to correspond with a variety of men [and they were all men] who had lived through these events; including Cosmo Rodewald and John Morpurgo. And I was a bit star-struck when I met up with Philip Toynbee, in a pub off Fleet Street. Though I can’t remember much of our conversation. And I had dinner, at the National Liberal Club, with Sydney Carter, a contemporary of John Morpurgo at Christ’s Hospital, but recall nothing of what he said. Carter was at the time a free-lance radio producer and occasionally folk singer. I would have been amazed had I known that he would become best known as a hymn-writer. When Lord of the Dance and One more step along the road, I go became two of the best-known hymns of the 1970s. But then I would have been equally amazed had I known that I would become a Church of England vicar.

What happened next ?

Of the lead characters in the story, John Cornford left his research scholarship at Cambridge to fight in the Spanish Civil War, as one of the first British volunteers, fought with POUM and with the International Brigades, and was killed at Lopera, near Cordoba, in December 1936. Esmond Romilly also fought in Spain in autumn 1936; and then eloped [back] to Spain with his second cousin Jessica Mitford. ‘Peer’s Daughter elopes to Spain’ was the headline in the Daily Express, and Anthony Eden as Foreign Secretary sent a warship to bring them back.

Esmond and Jessica were married in a civil ceremony in Bayonne, later emigrated to the United States; and Esmond was lost while flying as a navigator in a Whitley bomber over the North Sea in November 1941. His brother Giles was captured as a war correspondent in Narvik in May 1940, and spent the remainder of the war as one of the Prominente [well-connected prisoners] in Colditz castle.

John Morpurgo points out that eight of his contemporaries at Christ’s Hospital, who at school were mainly anti-militarist following the famous Oxford Union debate, had a distinguished cumulative war record with two DSOs, one DSC, and four ‘Mentions in Dispatches’ between them. Winston Churchill, the uncle of Giles and Esmond, adds his own unmistakeable postscript:

“Little did the foolish boys who passed the resolution dream that they were destined quite soon to conquer or fall gloriously in the ensuing war, and prove themselves the finest generation ever bred in Britain. Less excuse can be found for their elders, who had no chance of self-redemption in action.”

As for me: I was pleased to win a Trevelyan Scholarship, for the only piece of historical research I ever did. I promptly left school and spent the next six months working for the Inner London Education Authority at County Hall [as then was] and going to the cinema. After which I read history at Oxford, at Balliol, to no great profit. And over three years my enthusiasm for history steadily declined. And remained dormant for the next few decades.

December 2023