Birthday Girl

It was Susie’s BIG birthday in the week. We had a celebratory lunch with our friends Mike and Wendy at Left Field, a bijou restaurant on the edge of Bruntsfield Links. It was a Sunday lunchtime, and warm sunshine flooded in on our window table. The other window had an excellent view of Arthur’s Seat. My starter was squid rings with a spicy mayonnaise.As a main, Susie and I had pan-fried sea trout on a bed of courgette and fennel. With blood orange. The trout was excellent. Friendly service. The bill was not small, but not excessive. Susie paid – which made me feel like a toy boy ! A splendid birthday celebration.

Anthony Powell

One wet Saturday morning in the very late 1960s, when I was staying in the Pergamon guest-house in Pullen’s Lane, I went down into Oxford, to Blackwells, and and bought the first two volumes of Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past, in English translation, and the first two volumes of Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time. All in hard cover. I never read a word of the Proust books. And although I read the two Powell books, it was another three decades before I read the rest of the twelve volume sequence. Since Christmas I have been reading them again before taking them along to the charity shop.

Anthony Powell was born in Westminster in 1905, the son of a military family. He was always interested in genealogy, and traced his descent to land-owning families in Lincolnshire and in the Welsh Borders. He was educated at Eton and at Balliol College, Oxford.His Oxford friends included Maurice Bowra and the novelist Henry Yorke and Evelyn Waugh. He came down with a third class degree in history. [Nothing wrong with that.]

From 1926 to 1936 Powell worked for the publishers Gerald Duckworth & Co. Who published several of his early novels. In London his social life centred around formal debutante dances at big houses in Mayfair and Belgravia. As well as other authors, he got to know the painters Nina Hamnett and Adrian Daintrey and the composer Constant Lambert. In 1934 he married Lady Violet Pakenham, the sister of Lord Longford. During the war he served in the Welch Regiment, in South Wales and in Northern Ireland, and then in the Intelligence Corps. In 1952 he and his wife moved to The Chantry, a small, Regency country house near Frome in Somerset. He died in 2000 at the age of 94. He had written a score of novels, and a variety of other books of history and literary criticism, including four volumes of memoirs. On his death his publishers, William Heinemann, claimed him to be one of the greatest writers of the twentieth century.

A Dance to the Music of Time

Powell is best known for the twelve volume sequence A Dance to the Music of Time, which traces the stories of an upper class group friends from the First World War to the 1970s. The books were published at irregular intervals between 1951 and 1975. There is an enormous cast of characters. The central character is Nick Jenkins, a publisher and literary man, clearly based on Powell himself. Jenkins’ friends and family appear and reappear in a variety of settings, school reunions, deb dances, weekends in the country, family weddings and funerals. And seem to make a habit of marrying each other’s ex-wives ! Powell’s admirers celebrate him as an excellent observer of [a certain stratum of] English society. Who was well connected in a literary sense as well as socially.

The first book, A Question of Upbringing [published in 1951], opens with Nicholas Jenkins’ school-days in 1921-22; and introduces us to his friends Charles Stringham and Peter Templer, and also to the universally despised Kenneth Widmerpool. In the years that follow Jenkins works in publishing and attends a succession of deb balls in the later 1920s. At one such ball Widmerpool is humiliated when Barbara Goring pours a bowl of sugar over him. Jenkins is invited to the Templers’ house in Maidenhead, and embarks on an affair with Templer’s sister, now married to Bob Dupont. Mona Templer leaves her husband for J.C. Quiggin, a Marxist literary critic, who is now working as secretary to St John Clarke. During a weekend visit Jenkins meets the Tolland family: Erridge, Lord Warminster, head of the Tolland family, and his sisters including Isobel whom Jenkins decides to marry. From A Buyer’s Market [published in 1952] to The Kindly Ones [published in 1962]the narrative of the next five books revolves around a growing circle of friends and acquaintances, including: Jenkins’ erratic Uncle Giles; Professor Sillery, a well-connected Oxford don; Mark Members, a budding writer and poet; Sir Magnus Donners, a wealthy industrialist; the painter Mr Deacon and his consort Gypsy Jones; the novelist St. John Clarke; Jenkins’ fellow script-writer Chips Lovell; the musician and composer Moreland and his wife Matilda. And a few thousand others ! The settings are mainly in London, Foppa’s restaurant, Soho pubs, and a West End nightclub; but occasionally in country houses.

Things change with the seventh volume, The Valley of Bones [published in 1964]. The book is set in 1940 and Jenkins has joined his regiment, initially stationed in Wales. We meet his superior officer Captain Gwatkin and the alcoholic Lieutenant Bethel. The regiment moves to Northern Ireland. When both men are disgraced Jenkins reports to the DAAC at Divisional Headquarters – and learns that his new superior officer is Major Widmerpool. For me the three wartime books, The Soldier’s Art [published in 1966] and The Military Philosophers [published in 1968] are the strongest books of the series. Possibly because Powell himself is operating in a new and different [and larger] world. Jenkins fails to find a role with the Free French. Stringham, a recovering alcoholic, turns up as Mess Waiter for F Mess. But is posted to Singapore in time for the surrender. Chips Lovell and others are killed when a German bomb falls on the Cafe de Madrid. Another German bomb kills Lady Molly and Priscilla Tolland. By 1944 Jenkins is working in Allied Liaison and living in Chelsea. He is promoted to major, and leads a party of military attaches on a tour of France and Belgium. A meeting with Bob Dupont in Brussels reveals that Templer was killed under mysterious circumstances in the Balkans. By spring 1945 Widmerpool is engaged improbably to the wild and unpredictable, and sexually profligate, Pamela Flitton, Stringham’s niece. Together the books bear comparison with Evelyn Waugh’s Sword of Honour trilogy.

Simon Russell Beale as Major Widmerpool

Books do Furnish a Room [set in 1945-6, and published in 1971] brings Jenkins and his friends into the post-war world. The opening set piece is Erridge’s funeral, which is severely disrupted by the late arrival of the Widmerpools, J.C. Quiggin, and Sir Harold and Lady Craggs [formerly Gypsy Jones]. Jenkins agrees to work for Fission, a new magazine to be published by Quiggin and Craggs. Their much heralded new writer is the louche, penniless X. Trapnel, complete with long, black greatcoat and swordstick. Trapnel absconds briefly with Pamela Widmerpool, but she subsequently leaves him and throws his precious, not yet published, manuscript, into the canal.

There was a longer than usually delay before the publication of the final two volumes. Temporary Kings, set in the late 1950s was published in 1973. The book opens at a literary festival in Venice. A new character is Russell Gwinnett, an American, the prospective biographer of the late X. Trapnel. At an army reunion Jenkins hears further stories about Templer’s mysterious death. Moreland conducts at a Mozart party given by Odo Stevens and Rosy Manach. The book ends in late 1959 with Jenkins reflecting on the death of Pamela, apparently from an overdose while in bed with Gwinnett, and the situation of Moreland who is dying in hospital.

Hearing Secret Harmonies, set a decade or so later, was published in 1975. The twelfth and final book. In 1970 the Jenkins have allowed Scorpio Murtlock and his gang of hippie followers to camp on their land. Widmerpool is Chancellor of the local new university, but is converted to the counter-culture. Jenkins is part of the committee that awards a literary prize to Gwinnett for his biography of X.Trapnel. Widmerpool develops a growing link with Murtlock’s cult. There are reports of naked dancers celebrating the midsummer solstice at the Devil’s Fingers. As the book ends, Bethel, now one of Murtlock’s followers, brings news that Widmerpool has died on a naked run with the rest of the cult.

Somewhere in his four volumes of memoirs – I’ve been turning the pages of the abridged one-volume version, To keep the ball rolling, Powell determines that A Dance to the Music of Time will comprise twelve volumes. And wonders whether he will have the energy to carry it through. My feeling is that he didn’t. The final two volumes show a marked decline. And that Powell, living since the early 1950s in rural Somerset, became progressively out of touch with the world of the 1970s about which he was writing. For me there is a staleness about these two books, and a sense that the writer is merely going through the motions. That the books are on Autopilot.

Roman à clef

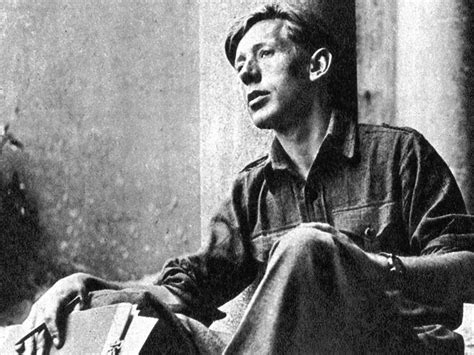

The memoirs also confirm what the reader may have long suspected. The books and their settings, and the characters who recur, are all drawn closely from Powell’s own life. Commentators have derived much pleasure from identifying the people on whom the characters are based. “Most novelists draw their characters and scenes in some degree from real life,” Powell acknowledges in Infants of the Spring. Nicholas Jenkins is clearly Powell himself: an Old Etonian, involved in publishing and script-writing in the 1920s and 1930s, who served during the Second War in the Welch Regiment and the Intelligence Corps. Charles Stringham is based on Hubert Duggan, a school and university contemporary, whose glamorous mother married Lord Curzon. Erridge, Lord Warminster, owes much to George Orwell, who had also seen time on the road. But the Tolland family also bear a likeness to the Pakenham family, into whom Powell married. Mona Templer is the model Sonia Brownell, who worked with Cyril Connolly on Horizon and later married George Orwell on his deathbed. J.C. Quiggin is thought to be based on C.P Snow, though there are also similarities to Powell’s nephew-in-law, Harold Pinter. St John Clarke is generally agreed to be based on the writer John Galsworthy. Moreland resembles Powell’s good friend the composer and conductor Constant Lambert. X. Trapnel is recognisably as Julian Maclaren-Ross, down to the dark glasses and sword-stick.

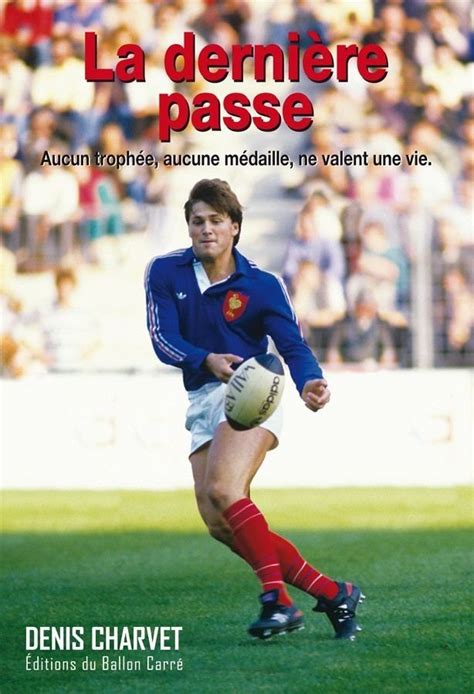

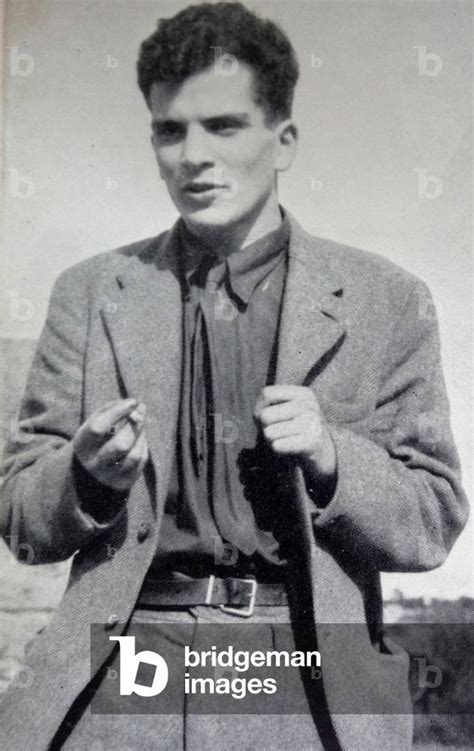

Julian Maclaren Ross

Scorpio Murtlock is thought to be based on Bruce Chatwin, the bisexual traveller and writer. The Quiggin twins may be based on the Jay twins, the much photographed daughters of Douglas Jay who were at the University of Sussex in the 1960s.

There are divergent theories about the model for Kenneth Widmerpool. The consensus is that he is based on Sir Reginald Manningham-Buller, a lawyer widely known as Bullying-Manner, who became Lord Chancellor in the Macmillan government and was elevated to the Lords as Viscount Dilhorne. The other possibility is that Powell drew on Denis Cuthbert Capel-Dunn, under whom Powell served in the Intelligence Corps in 1943. Capel-Dunn, a barrister , also known as The Papal Bun, was said to be extremely fat, extremely ambitious, and totally humourless. He was killed in a plane crash in 1945 returning from the San Francisco Conference.

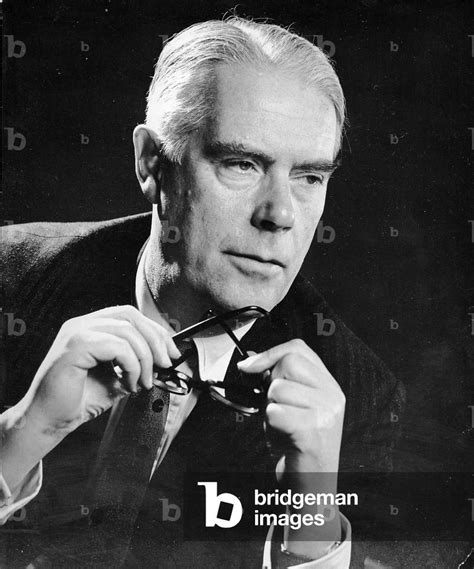

Sir Reginald Manningham-Buller

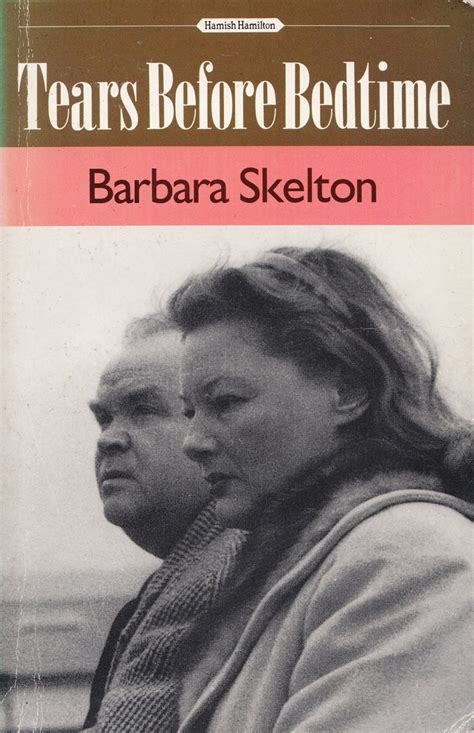

The model for Pamela Flitton is undoubtedly Barbara Skelton, an English socialite and novelist. Skelton , born in 1916, grew up in British India. In the Second War she was recruited into the Foreign Office by Donald Maclean, the Soviet spy, and then assigned to Cairo. In 1943 she became the ‘official mistress’ of King Farouk, whom she described as very sweet with a good sense of humour but incredibly mean. After Farouk she was married successively to Cyril Connolly and to George, later Lord, Weidenfeld; and had affairs with, among others, Peter Quennell, Felix Topolski, Charles Addams, John Sutro, and Alan Ross. The story is told in her two volumes of memoirs, Tears before Bedtime, and she has a walk-on part in one of Jeremy Lewis’s books of publishing memoirs.

Envoi

On his death in 2000 Powell was hailed as “one of the greatest English writers of the 20th century”. And as “an excellent observer of British society”. A Dance to the Music of Time is certainly a highly ambitious sequence of novels., And the ambitious, widely disliked, humourless Widmerpool has passed into the English language. [Very many years ago I was having lunch with a civil servant, an urban planner, in a basement restaurant in Regent Street, and she described someone to me as “the Widmerpool of the planning world”; and was surprised when I failed to recognise the reference.]

Powell himself was an acid critic of some of his contemporary writers. {He described Laurie Lee as “utterly unreadable”, Graham Greene as “absurdly overrated”, Virginia Woolf as “humourless, envious, and spiteful”.] If you have a nostalgia for a slower-paced, educated, literate, upper middle-class world, and plenty of time to spare, then A Dance to the Music of Time might suit you very well. For myself, I find the narrator, Nicholas Jenkins, a cold fish, and the whole sequence urbane, pretentious, sometimes witty, and at least two books too long.

I saw a good, three-part documentary on the Tony Blair years on television the other night. One commentator described his premiership as a ‘Golden Age’. Compared with political debate and leadership today. So – I think I’ll look again at the Diaries of Chris Mullin, a not uncritical supporter of Blair and the finest political diarist of his generation.

February 2026