On the home front

We have been back from Grenoble for some ten days. It has rained steadily each day, and the boiler has gone on the blink. In the garden the ground is sodden, and I am wondering whether to allow the pond to overflow and turn it into a boating lake. The only good thing is that the little girls passed through, and Jem & Ann and the children came to stay. Which was excellent. Freya wrote in the Visitors’ Book that staying here might have prepared her for an expedition to the Antarctic.

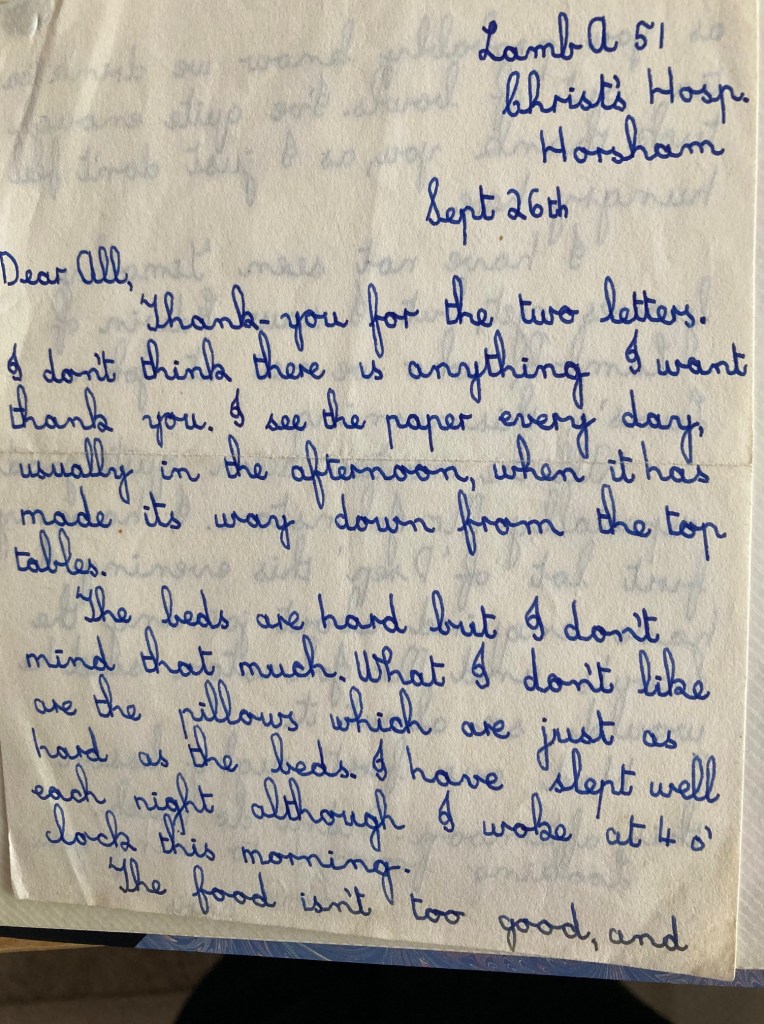

Going back to school

I left school, Christ’s Hospital, 60 years ago at Christmas. At the end of the Michaelmas Term 1963. The unchanging school leaving service was undiluted sentiment: the Headmaster, ‘George’ Seaman, reading [very slowly] from Philippians 4: “Rejoice in the Lord always, and again I say, Rejoice … Whatsoever things are of good report, think ye on these things”; and the Nunc Dimittis; and singing a hymn, possibly The day thou gavest, Lord, is over, with three slurs to the line [there may be a more technical term for this]; and the Leaving Charge, again read by the Headmaster: “I charge you never to forget the great benefits that you have received in this place, and in time to come, according to your means, to do all that you can to enable others to enjoy the same advantage. And remember that you carry with you, wherever you go, the good name of Christ’s Hospital.” And the giving to each leaver of a black leather-bound Bible, the RV I think.

After the service leavers would dash round saying Good-bye to selected masters. Or gather for a surreptitious fag down in the Tube or on the roof of the bogs in the car park. Or possibly both.

I spent nearly seven years of my life at CH, going there at the age of 11 in the summer of 1956. None of my family had ever dreamed of going to boarding school. And the very little I knew about such schools came from reading The Fifth Form at St Dominic’s, [pub 1881] by Talbot Baines Reed, originally written for the Boy’s Own Paper. And published by the Religious Tract Society. I guess I must have found an elderly copy in my grandparents’ house. And from reading the Jennings books by Anthony Buckeridge. On balance the latter books were probably more helpful. [The author himself was at school at Seaford College, and later taught at St Lawrence, Ramsgate.]

Life as very different in the mid-50s. Pop music, transistor radios, mobile phones, colour television, foreign travel, the Internet, and girls had not yet been invented. At least not in my world. The first several years at CH seem in retrospect to consist largely of a lot of school work, a lot of running around in wet games clothes, and of marching into meals three times a day in the enormous Dining Hall. At primary school we had done little other than arithmetic and English, and play football. At CH a host of things were new to me. I quite enjoyed Latin and History and Geography [I won a Geography prize at the end of my first year], though the geography lessons rarely got beyond the Weald; I was easily intimidated by French; and bored by Physics [one teacher still spelled Cathode with a K] and Chemistry, which largely consisted of heating things up in test tubes; and even more bored by Mathematics. Especially when simple arithmetic and problem-solving morphed into algebra and geometry and trigonometry. After the first two years I gave up on Geography and embarked on classical Greek. Which I really enjoyed.

Outwith the classroom there were games every afternoon. Most often rugby in the winter. Followed by splashing in muddy water in a communal trough. Other afternoons we ran round bits of the local countryside for an hour or more. In extremely bad weather we played ‘heartyball’ in the muddiest patch the monitor could find. I was hopeless at gym, which took up one afternoon a week. While contemporaries swung on ropes and walked on their hands, I could never manage more than a simple vault over a pommel horse. I was better at cricket, which took an enormous amount of time in the summer. We practised on Mondays, Tuesdays, and Thursdays, and played competitive house matches on Wednesdays and Saturdays. I was an accurate, if the world’s slowest, bowler, and an erratic batsman; but I captained the house second leagues team for a season.

We lived in boarding houses of some 50 boys each. The houses were named after famous Old Blues. My house was Lamb A, named after Charles Lamb – of whom I had at least heard ! And Coleridge too. Middleton was, I think, an obscure bishop; and Maine possibly an academic lawyer. Each house had a big day room, in which we lived for much of the time, and two dormitories each heated by a single radiator. The day room contained four long narrow tables, at which we did our prep, and on which we played table tennis. Our games clothes were kept in communal, house changing rooms, from which things regularly disappeared. My swimming trunks disappeared my first summer term, and I had to swim in the altogether for several weeks. Like one of the characters in a Jonathan Coe book. It’s a wonder I’m not still in therapy.

My house master, Johnny, taught modern languages. He had been educated at the Royal Masonic School, Bushey, and then at Downing College, Cambridge; and had spent the war as an interpreter with Polish troops. We suspected that his red complexion came from eating too much bortsch. He invariably wore an old tweed sports jacket and grey flannels and brown shoes. He was a bachelor, and a philistine, and a bigot, who exhibited many of the less attractive characteristics of public school- masters of his generation. His all-purpose put-down was ‘Bolshy’, which incorporated everything from would-be intellectuals to modern poetry to socialist politicians to pop music.

The other masters were a mixed bunch. Many of the senior house-masters were much like Johnny; bachelors, instinctively conservative in their politics and their social attitudes, ill at ease with women, and apparently happy to stay in their posts until death or retirement whichever came first. [The pattern is well portrayed in TC Worsley’s Flannelled Fool, a book about the author’s experience of teaching at Wellington in the 1930s, a book that I didn’t discover for another six or seven years.] Several of these masters, like Arthur Rider and ‘Pongo’ Littlefield, had served in the war, and then returned to the familiarity of teaching as the only thing that they knew.

The setting

CH was a ‘religious, royal, and ancient foundation’, which had celebrated its quatercentenary in 1953. It had in origin been a charitable foundation in the City of London, in Newgate Street, which had relocated to Sussex, to West Horsham, very early in the twentieth century. The foundation bought 1,200 acres of land from a bankrupt dairy company, and engaged Sir Aston Webb, the architect of the Queen Victoria Memorial and the facade of Buckingham Palace, and of County Hall, all in London, and of much of the University of Birmingham, to design the buildings. These include 8 boarding houses arranged along a central avenue, all built in a distinctive yellow-red brick [bought at a discounted price], an enormous quadrangle flanked by colonnades, the chapel, and the dining hall, which is dominated by an 86-foot-long painting by Antonio Verrio which depicts the foundation of the Royal Mathematical School by King Charles II in 1673.

The complex of buildings is ‘ringed by downs and woodlands fair’, according to one of the school hymns. More prosaically it is surrounded by a patchwork of rugby and cricket pitches, including the First XI square which was reputed to be the best cricket wicket in Sussex. The southern region trains to Worthing and to Brighton are hidden from sight in railway cuttings, beyond which lie Shelley Wood [no known connections to the poet] and the gently sloping Sharpenhurst. It was and is a delightful setting, though many trees were lost in the Great Storm of 1987.

The school uniform, worn day in and day out, was knee breeches with silver buttons, yellow knee socks, clerical bands at the neck, and a blue full length coat, worn with a leather girdle and again with silver buttons. Hence the common name ‘the Bluecoat school’. It sounds odd, and maybe looks a bit odd, but since we all wore the same thing it seemed perfect normal. Not quite the same thing. ‘Button Grecians’, an academic distinction, wore blue coats with velvet collar and cuffs and with more, noticeably bigger, buttons.

History Grecians

The first 4 years at CH are a bit of a blur. After GCE O-levels [I took 7 O levels; did best in classical Greek; worst in Physics-with-Chemistry] in 1960, we were free to specialise. I became a History Grecian, and spent the next 3-plus years doing mainly medieval English and European history, without ever getting much beyond 1215. Apart from history, we did some Latin and French, concentrating on reading skills; and some token Divinity, which comprised a very dull and leisurely look at John’s Gospel, taught by the Headmaster, ‘George’ Seaman. It was a skeletal timetable, which left plenty of time for sitting in the Library or sun-bathing in the Garden Quad.

The history master was Michael Cherniavsky, from a White Russian family, educated at Westminster and Balliol. He had a big forehead, wiry greying hair, a slight lisp, and a penchant for wearing double-breasted suits, often enough with the jacket not matching the trousers. Physically he seemed a bit lob-sided. But he was very widely well-read, had strong liberal views, and a balanced intellect. Which enabled him to grade our essays with fine distinction between, say, AB/BA and B++?+.

History Grecians as a race were independent minded, generally favoured left-wing views and causes, and were sceptical about authority. All things which Johnnie hated ! Two History Grecians in Lamb A a few years ahead of me were Alan Ryan, who subsequently became an academic philosopher, an authority on John Stuart Mill, and Warden of New College, Oxford; and Stuart Holland, who went from Balliol to St Antony’s, worked as an economist in the Cabinet Office, and became for a few years the [Bennite] Labour MP for Vauxhall.

As Michael’s pupils we wrote essays on Charlemagne, and Otto I and Otto III, and on Pope Innocent IV, and on Franciscans and Dominicans; and, closer to home, on King Alfred, and the Norman Conquest, and the intricacies of feudalism, and on the civil war between Stephen and Matilda. In between I was encouraged by Michael to work on a project on ‘Anti-Fascism in the English Public Schools, 1933-39’. Which brought me into contact with the Spanish Civil War, and dinner in the National Liberal Club with Sydney Carter [the hymn-writer], and lunchtime drinking with Philip Toynbee in a pub off Fleet Street.

We were all children of promise once … The expectation was that we would all win awards at Oxford and go on to academic distinction. Sadly, it didn’t quite turn out like that. But next week I am going down to CH, for a 60 Years On Leavers’ Reunion, and I’ll be meeting a small group of people some of whom I haven’t seen for 50 years. In a slightly perverse way, I find that I’m looking forward to it

April 2024