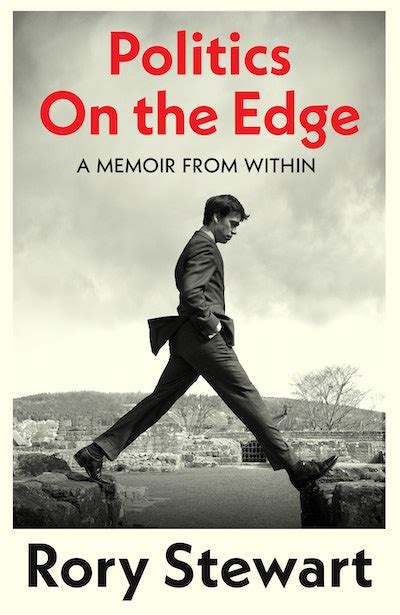

Politics on the Edge

Our week in the Hebrides last month felt like living on the edge of the map, if not the edge of the world. I took three books with me to read, and came back with eight ! One of them Tony Judt’s The Memory Chalet, which I will write something about later, I found in a clean hardback copy in a charity shop in Callander. One of the books which I didn’t read while we were away, but which I have read with much pleasure since we got back to Edinburgh is Rory Stewart’s Politics on the Edge.

Rory Stewart

It is difficult to understand just how much Rory Stewart, who is 51 this year, managed to fit into his first four decades. He was born in Hong Kong in 1973, the son of Brian Stewart, a colonial official and diplomat, who may have been a spy. His education was that of any privileged, upper class Tory: the Dragon School, Eton, and Balliol. Where he was a few years behind Boris Johnson. In between school and uni he held a short-term commission in the Black Watch, his father’s regiment. After graduating he joined the Foreign Office and served in Indonesia and in Montenegro in 1997-2000. He then took a two year sabbatical to walk across Iran and Pakistan, as recounted in his book The Places in Between. From 2003 to 2008 Stewart worked in southern Iraq, and then in Afghanistan where he was responsible for setting up the charity Sapphire Mountain. From 2008-10 Stewart held a university teaching post in the United States. In the course of his travels Stewart learnt Arabic, Dari, and Pushtu. David Cameron called him ‘the Sandy Arbuthnot of our time’, based on the exotic character in John Buchan’s Greenmantle. [One of the great boy’s thrillers.] I don’t think it was intended as a compliment.

Politics on the Edge

At Harvard his colleague Michael Ignatieff, the Canadian author and academic, encourages him to become a doer and not just a commentator. His book Politics on the Edge is a detailed account of his ten years in politics, as a Tory candidate, as a back-bench MP, as minister, and as leadership candidate. It is a rollicking good read. And, as Lord [Rowan] Williams commented, “an excoriating picture of a shamefully dysfunctional political culture”. To be honest there is a limit to how much I want to know about the current Tory party. And the book may be 50 pages too long. But Stewart is a rare politician who can write; these are the best written political memoirs since Roy Jenkins and Denis Healey. Which offer some sharp and sometimes savage portraits of his Tory party colleagues.

Cameron

Stewart is a self-confessed admirer of the military, the monarchy, and traditional Britain; a believer in limited government and individual rights; prudence at home and strength abroad.He is attracted by what David Cameron called ‘The Big Society’. When he is given 15 minutes in Cameron’s diary, they meet in Portcullis House, a glass and stone cube with a cluster of thick, dark chimneys, looking as “though a 1980s retail block was experimenting with the identity of a Victorian power station.” The four men in Cameron’s outer office, with floppy hair and open-necked white shirts are all Old Etonians. Stewart notes that Cameron’s inner team, and indeed all his close friends, are drawn from an unimaginably narrow social group. The exception, Kate Fall, his deputy chief of staff, and George Osborne, the shadow chancellor, “only appeared to have gone to Eton”.

Cameron clearly had little idea who Rory Stewart was and was uninterested in his views on Iraq and Afghanistan. When Stewart expresses a desire to serve as a minister and to be part of delivering policy. Cameron reprimands him sharply: “If you are lucky enough to find a seat and to be elected, you will find that being a back-bench Member of Parliament is the greatest honour you can have in life. I may be lucky enough to become prime minister, but when I cease to be prime minister I will return with great pride to the back benches as Member of Parliament for Witney for the rest of my life”. Stewart reflects that, seven years later when Cameron resigned as prime minister, he couldn’t resign his parliamentary seat quickly enough.

When he wins the 2015 election Cameron, freed from the Lib Dem coalition, has seats to fill in his government. Stewart and others are hopeful. But they are disappointed. “I divide the world”, Cameron liked to say, “between team players and wankers; don’t be a wanker”. The team players are those who parrot the party line with fervour and without embarrassment. His younger promotions – Priti Patel, Liz Truss, and Matt Hancock – “took this to a vertigo-inducing extreme”.

Eventually Stewart is summoned to 10 Downing Street, and dressed in his best dark suit with cappuccino all over his crotch, is given the most junior job in the Department of Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs. He inherits a team of extraordinarily unforthcoming civil servants, and a cupboard with bottles of tequila and Aperol, and a desk that is empty apart from a black plastic comb. His boss, the marginally younger Liz Truss, commands him to prepare a ten-point plan for the national parks. He has 3 days to do it, so that it can be in the Telegraph on Friday.

Johnson

Stewart first met Boris Johnson, another old Etonian, in a sandbagged shipping container in Iraq in 2005, when he was working there and Johnson was a backbench MP. When they meet again after the 2017 election, it is in the vast imperial office of the Foreign Secretary, now decorated with a cycle helmet and a London Tube map. “His hair seemed to have become less tidy, and his cheeks redder since I had first met him in Iraq, as though he was turning into an eighteenth-century squire, fond of long nights at the piquet table at White’s. This air of roguish solidity, however, was undermined by the furtive cunning of his eyes”. Stewart is trying to persuade Theresa May to make him a minister in the Foreign Office as well as a DfID minister, so that he can think about a way to combine the different diplomatic and development projects. He explains to the Foreign Secretary that he has spent twenty years in the Middle East and Asia and speaks three Asian languages. Johnson amused response is to make him “a Balliol man in Africa”.

A few weeks later, at a Conservative Party event, Stewart is approached by a close aide of the wealthy Russian Evgeny Lebedev. He is invited to stay for a weekend at a castle in Italy. A celebrity is coming who was a topless model in the Sun. Stewart explains politely that he can’t possibly go; Lebedev’s father was an officer in the KGB. “Oh, don’t worry about that”, the woman replies. “Boris Johnson is coming, and he is the Foreign Secretary”.

Stewart rightly identifies Johnson’s habit of making outrageous and often racist remarks under the pretence that it might be a joke. Thus he described foreigners as people who “cooked goat curries on campfires” and “wore veils that made them look like letter-boxes”. He said, “Islam will only be truly acculturated to our way of life when you can expect a Bradford audience to roll in the aisles at Monty Python’s Life of Muhammad”. He said the things in a way that allowed racists to believe that he agreed with them, while others convinced themselves that he was only joking. His supporters watched him as if they were “watching a 1950s cartoon, where Boris could sprint like the roadrunner off a cliff, and experience some surprise but little consequence.”

Truss

In his first government job Stewart’s boss was Liz Truss. David Cameron, he realises, had put in charge of environment, food and rural affairs a Secretary of State who openly rejected the idea of rural affairs and who had little interest in landscape, farmers, or the environment. He wonders if there was any job for which she was less suited – apart perhaps from making her Foreign Secretary. She commissions Stewart to write a twenty five year plan for the environment, but rejects three separate drafts for no specific reason. Stewart travels up to Scotland to visit his ninety-three year-old father. Who dies that weekend. He returns to London and Truss asks how his weekend had been. He explains about his father. She nods. And asks when the twenty-five year plan will be ready.

When Theresa May asks Stewart to become Minister of State [for prisons] in the Ministry of Justice, Truss had already been and gone. During her short time as Secretary of State for Justice, Truss had cut prison budgets drastically, sold off office space in the department building, and got rid of sundry managers. Partly in consequence Stewart finds a Probation Service that was losing control of dangerous ex-offenders, lawyers on strike because of cuts to legal aid; and prisons which were filthy, drug-ridden, and violent. Privatisation meant that companies were charging £172 million for maintenance work that the government used to do for £42 million. Drugs were arriving regularly on drones. A previous minister had suggested using eagles to prevent them. Liz Truss had stood at the despatch box to tell the Commons: “I was at HMP Pentonville last week. They’ve now got patrol dogs who are barking which helps to deter the drones.” One MP was provoked to shout at her: “You are barking.”

Leaving aside the personalities, Stewart makes the point very clearly that it is impossible for anyone to simultaneously, say, oversee DfID’s work in Africa, to function as part of cabinet government in the Commons, and additionally to represent his constituents in northern England. [Richard Crossman made a similar point a generation earlier: that Cabinet ministers are rarely able, because of lack of time. to do more than advance the briefs prepared by their civil servants.] Rory Stewart also deplores the fact that cabinet ministers change jobs and departments all too frequently, often because the prime minister wants to promote, or demote, someone else. So that ministers don’t have time to master their briefs or to see through policy change. And he deplores the reluctance of the British system to bring in outside experts, from the business or academic or military world.

Whither now ?

Stewart resigned from the Cabinet when Boris Johnson became Prime Minister in 2019. Later the same year he had the Conservative Whip removed because of his voting over BREXIT, and stood down as MP at the following election. Since then he has written Politics on the Edge, worked in Jordan for two years for The Turquoise Foundation, and returned to the academic world with a post at Yale University. He also co-presents The Rest is Politics with Alistair Campbell, an entertaining and well informed look at the current political scene. There is an unsubstantiated rumour that he may be a candidate to become the next Chancellor of the University of Oxford, Following Chris Patten. Two uncommonly civilised Balliol Tories.

Envoi

I shouldn’t be sitting here writing this. I should be working in the garden, which has been at its best in recent weeks. Susie is struggling a bit with an arthritic hip and walking with two poles. I seem to have caught it from her. Sitting down is OK, but getting up again is very slow and uncomfortable. I walked along the river Tyne from East Linton to Haddington on Wednesday. But it was hard work and further than I had remembered. Next week I have a cataract operation. So at least I’ll be able to see where I’m going !

July 2024