After last week’s very effective cataract operation, I have been looking through a glass more darkly than usual. A big Thank You to Dr Mary MacRae at the Princess Alexandra Eye Pavilion and to the NHS.

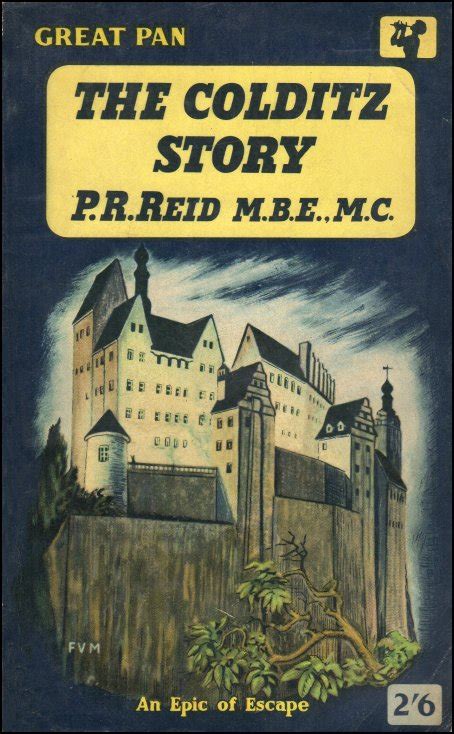

The Colditz Story

In the word’s most chaotic second-hand bookshop, in the Seamen’s Mission in Mallaig, in June, I found a clean copy of Ben Macintyre’s Colditz: Prisoners of the Castle. It is yet another good read from the prolific Ben Macintyre, who seems to write books as fast as I can read them. Since A Foreign Field [published in 2001], the story of Robert Digby, a young British soldier trapped on the wrong aide of the lines in 1914, and his doomed affair with the French girl Claire Dessenne, Macintyre has written another fourteen books, many of them best-sellers.

I grew up in the 1950s on war stories, many of them published by Pan Books. The first ‘grown-up’ book I owned was Guy Gibson’s Enemy Coast Ahead. And soon afterwards came the two books by Pat Reid: The Colditz Story [published in 1952] and Latter Days at Colditz [published in 1953]. Reid was born in India of Irish parents. He graduated from King’s College, London, in 1932 and trained as a civil engineer. In June 1940 he was taken prisoner near Cassel. He was imprisoned at Laufen castle in Bavaria, and instrumental in one of the earliest escapes of the war in September 1940. He and five others tunnelled out of the camp, and walked by night, without papers, making for Yugoslavia. They were recaptured at Radstadt in Austria, and Reid and the so-called ‘Laufen Six’ were promptly sent to Colditz, the fortress that was said to be escape-proof.

The Laufen Six

At Colditz Reid served as the Escape Officer, responsible for overseeing all the British escape plans. In October 1942 he himself escaped with three other officers. They had fake identities as Flemish workmen, travelled by train to Tuttlingen, and crossed from there into Switzerland. He remained in Switzerland until the end of the war working for the Secret Intelligence Service [MI6], and subsequently worked in the British Embassy in Ankara and for the OECD; and eventually returned to his original work as a civil engineer. He died in 1990.

Reid might be thought to be the founder of the subsequent ‘Colditz industry’. His first book, The Colditz Story. served as the basis for the 1955 film of the same name. John Mills played Reid, and Reid himself worked as technical advisor. I saw the film in, I think, the Plaza at Southfields, in 1955. Stirling Castle stood in for Colditz, which, in East Germany, would have been out of bounds in the 1950s. Reid’s two books were reissued in 1962 as Colditz, and were the basis for the BBC television series Colditz which ran from 1972-74. Reid again served as technical advisor. And again Stirling Castle stood in for Colditz. [The producer incidentally was Gerald Glaister, who subsequently produced Secret Army. In which the central character was played by Bernard Hepton, who had played the German Commandant in the Colditz series.] Pat Reid also collaborated on a boardgame, Escape from Colditz, which was an official licensed tie-in to the television series.

The books and the television series were a great success. But not everyone was impressed. Some fellow prisoners were unconvinced by Reid’s assumed expertise. The books are unreliable in some details, which is unsurprising since Reid himself was imprisoned at Colditz for less than half the duration of the war. There has also been some criticism of his Boys Own Paper style in which the prisoners, all good public school chaps, are always ‘sticking one up to the goons’.

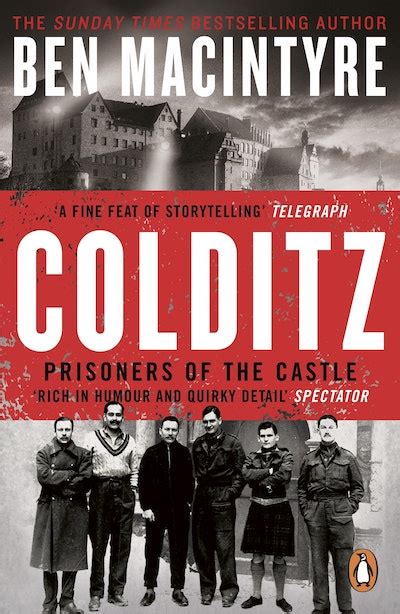

Ben Macintyre: Colditz

Macintyre’s book was published in 2022 and the paperback in 2023. His book revisits the men and stories of earlier books, but also reveals a more complex and darker side to the Colditz story.

The book emphasises the forbidding nature of the castle; this vast 700 room fortress perched above the town on a cliff, which had been used down the centuries as a prison, a psychiatric hospital, as somewhere for incarcerating undesirables. The German plan was to collect all the trouble-makers and inveterate escapers in one place, in a castle that it would be impossible to escape from. There were two problems about this: first, the building was old and full of holes and hidden passages and bricked up drains; secondly, grouping all the naughty boys together creates a culture of defiance.

Macintyre emphasises too that this was an officers’ camp [an oflag], which gave the prisoners a certain status under the Geneva convention.Officers were treated better than ordinary soldiers. The prisoners at Colditz were waited on by orderlies, ordinary soldiers, who made their food and organised their bath-water. There was a wide social gulf between the officers who were expected to escape and the orderlies who were under their command and not allowed to escape.

As well as different classes, there were initially at least multiple nationalities. The first prisoners in the castle were Polish, who were adept at lock-picking; followed by French, Belgian, and Dutch, and latterly Americans. They didn’t always get on well. An early Colditz Olympic games in August 1941 brought out national stereotypes; the Poles were keen to win, the French were very laidback, and the British treated it all as a joke and came last at everything.

Less attractively, there was a significant tension between the French officers and the French-Jewish officers who were segregated by the Germans into a different dormitory in the attic. Immediately called the ghetto. Some British officers were horrified by this. But the British were themselves very intolerant of the only non-white officer among them, an Indian doctor called Birendranath Mazumdar who was in the Royal Army Medical Corps. He was treated with suspicion by fellow officers and was told that he was not allowed to escape because of the colour of his skin . He later went on hunger strike and insisted he be moved to an all-Indian prison in occupied France. From there he managed to escape and walk 700 miles across the border into Switzerland.

As had previously been told, there were a variety of music groups in Colditz, an orchestra, a Hawaiian string band, a Polish choir; and regular drama productions of high quality. The British also created a variety of clubs; bridge, chess, and sports clubs. And there was a full programme of lectures on a wide range of topics. Including some [frowned upon by many] Marxist lectures by the ‘Colditz Commies’; Micky Burn, an old Wykehamist, journalist and poet, captured during a commando raid on St Nazaire, and Giles Romilly, the first of the Prominente, a journalist and civilian captured in Norway. [Giles was the older brother of Esmond Romilly, the prime mover of Out of Bounds, who had now volunteered for the Royal Canadian Air Force and was ‘Missing – presumed killed’ flying over the North Sea in 1941.]

Contrasting Colditz characters

The senior RAF officer in Colditz was Wing Commander Douglas Bader, a celebrated flyer who had survived the amputation of both his legs following a pre-war flying accident in 1931. Bader was another schoolboys’ hero of the 1950s, portrayed by Kenneth More in the 1956 film Reach for the Sky. In spite of his tin legs, the pugnacious Bader had forced his way back into operational flying, and was leading 616 squadron when he was shot down in August 1941 over northern France. Bader was famously brave and threw himself energetically into the life of Colditz; he conducted the orchestra, played goalie in games of stoolball, and became the self-styled ‘goon-baiter-in-chief’.

But Bader was also arrogant, domineering, and searingly rude, especially to those he deemed of lower status. As Macintyre acknowledges, Bader was generally loathed by his ground staff. In Colditz Bader was waited on by his diminutive, Scottish medical orderly, Alec Ross. Who served his breakfast in bed, and then carried the heavyweight officer down two flights of stairs for his bath and back up again. When Ross was offered the possibility of repatriation to the UK, Bader blocked it. At the end of the war when the prisoners were liberated, Bader jumped rank and secured a flight home two days before everyone else. Afterwards, back in the UK, he rang Ross, thoroughly berated his servant for not bringing Bader’s spare legs back with him; and never spoke to him again.

A very different character was Captain Julius Green, a Jewish dentist from Glasgow. He described himself as “a devout and practising coward, a short-sighted, flat-footed dentist with a tendency to overweight”. This may have been camouflage. Green was not only a fine dentist, but he was also a secret agent for British intelligence. Patients tend to confide in dentists, the German ones included, and ‘Toothy’ Green became one of the most prolific coded letter-writers of the war. Somewhat improbably, the unmarried dentist also became an unofficial counsellor, advising his patients on their romantic and marital anxieties. After the war Julius Green returned to a dental practice in Glasgow, his personal history largely unknown until he published From Colditz in Code in 1971.

Envoi

I was delighted to have an opportunity to visit Colditz in 2005. Susie and I had driven from Lyon to stay with cousins in Munich, and thence on to Prague. After a brief visit to the magnificently rebuilt Dresden, we arrived in Colditz in the late afternoon, discovered the only hotel in town was full, and ate a hearty Saxon meal in the restaurant which we shared with the local male voice choir.

At Colditz August 2005

In the morning we did the Colditz Castle tour with a package tour of British men, all vying to show off their knowledge of Colditz escaping and escapers. Just looking at the entrance to the famous French tunnel brought on claustrophobia. The dominant impression was the height of the castle buildings, and the smallness of the gloomy and sunless courtyard where the prisoners spent much of their time. And then we came away, well equipped with both civilian clothing and papers, to make our way to Magdeburg. There was talk in 2005 of turning the castle into a kind of theme park, which British package holiday-makers would try to escape from. I don’t know if that ever happened.

At Colditz August 2005

August 2024