I have always thought of France as a sovereign nation; a centralised country that occupies an easily identifiable chunk of western Europe; a country that was our ally in the two world wars of the twentieth century; a country that has a proud record in rugby’s Six Nations, and which won the football World Cup in 1998 and 2018, and were runners up in 2006 and 2022. But this easy assumption has been challenged by a fascinating book by Graham Robb; another bargain from the OXFAM bookshop in South Clerk Street.

The Discovery of France

Graham Robb [born 1958] is British historian and writer, who specialises in French literature. He did a degree in Modern Languages at Oxford, completed a doctorate at Vanderbilt University, Tennessee, and held a junior research fellowship back at Oxford before leaving academia in 1990. Between 1994 and 2000 he published biographies of Victor Hugo, and Balzac, both of which won book awards. His book The Discovery of France, sub-titled A historical geography of France from the Revolution to the First World War, was published in 2007. His essential thesis is that France was for centuries a largely unknown and amorphous country; a land of ancient tribal divisions, prehistoric communication networks, and pre-Christian beliefs. Until the end of the nineteenth century, Julius Caesar’s De bello gallico was still being quoted as a useful source of information about the inhabitants of the vast interior.

The undiscovered continent

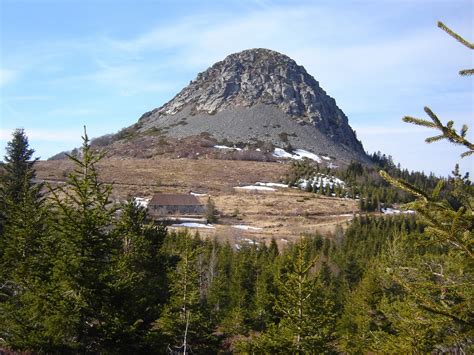

In the early 1740s a young man from Paris was exploring Le Gerbier de Jonc, a little-known mountain of phonolithic rock in the Mézenc range, near the source of the river Loire. The isolated villagers seeing him pointing strange instruments at barren rocks assumed he was up to no good; and hacked him to death. He was in fact a young geometer, part of a team assembled by the astronomer Jacques Cassini to draw up a reliable map of France. A century later this was still a remote and dangerous area of France. A nineteenth century geographer recommended viewing the Mézenc region from a balloon, but “only if the aeronaut can stay out of range of a rifle”. In 1854 Murray’s Handbook for Travellers recommended visitors who left the coach at Pradelles not to expect a warm welcome. “There is scarcely any accommodation on this route, which can hardly be performed in a day; and the people are rude and forbidding.”

Le Gerbier du Jonc

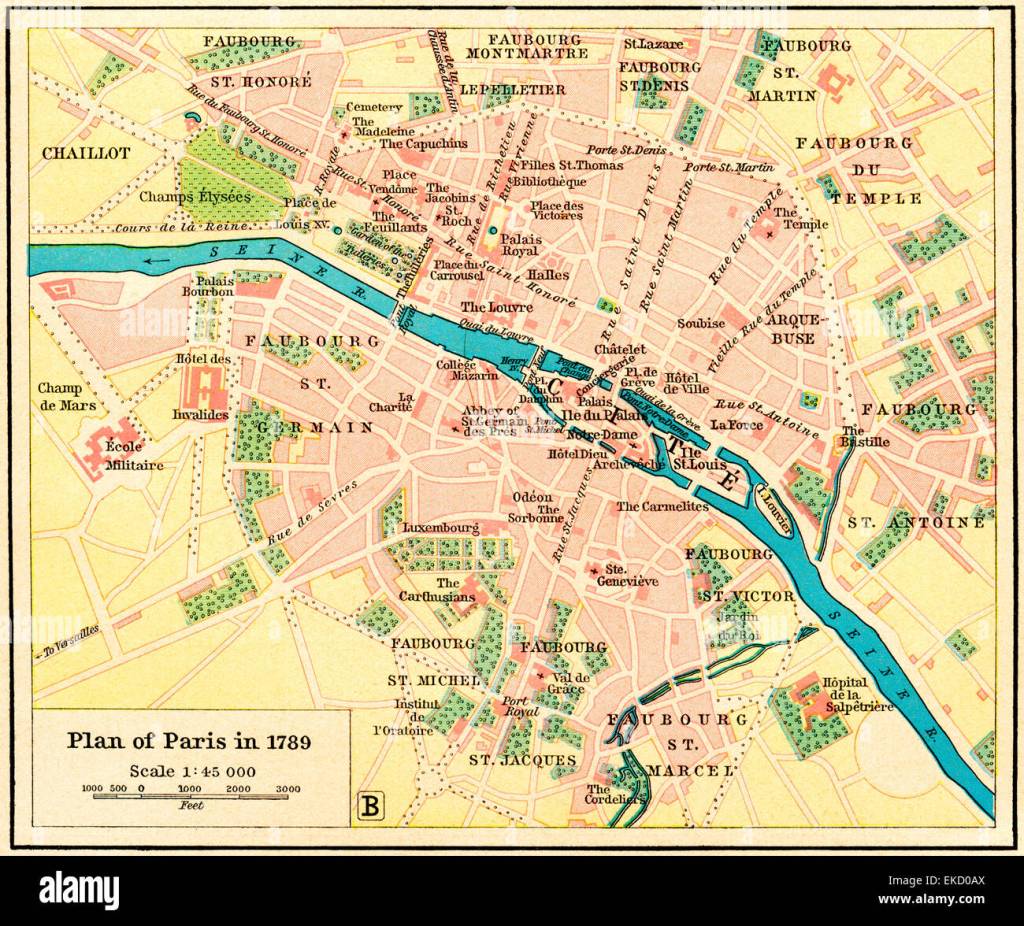

Pre-Revolutionary France was composed of a number of feudal provinces or généralités. Some provinces had regional parliaments and imposed their own taxes. Some of the internal borders derived from the division of Charlemagne’s empire in 843. The two hundred thousand square miles of Europe’s biggest country still operated on medieval times. On the eve of the Revolution, France was three weeks long [Dunkirk to Perpignan] and three weeks wide [Brest to Strasbourg]. Four-fifths of the population was rural. But there were enormous remote and empty areas. The wild boy known as Victor de l’Aveyron lived alone for several years before being captured by peasants in 1799 and put on display as a freak of nature. The ‘wild girl’ of the Issaux forest, south of Mauléon, was lost for eight years before being discovered by shepherds in 1730, alive but speechless.

Paris drew internal migrants. In 1801 more people lived in Paris [550,000] than in the next six biggest cities combined [Marseille, Lyon, Bordeaux, Rouen, Nantes, and Lille]. In 1886 Paris was the same size as the sixteen biggest cities. Yet until 1860 Paris covered an area of only thirteen square miles [roughly twice the size of the Eurodisney site].

The tribes of France

Before the mid-nineteenth century, few people had seen a map of France; few people had heard of Charlemagne or Joan of Arc. The state was perceived as a dangerous nuisance: soldiers had to be fed and housed; bailiffs seized property; lawyers settled disputes and took most of the proceeds. Caesar described Gaul as “divided into three parts”. But he also observed that it was sub-divided into a host of innumerable tiny regions. The basic unit was the pagus, the area controlled by a tribe. The term pays remains a popular designation, often borrowed to promote local development and tourism. In 1937, when compiling his nine-volume Manual of Contemporary French Folklore, Arnold von Gennep, warned the list of pays was incomplete because “some pays are still unknown”. The pays rather than the state was the fatherland of the nineteenth century peasant. The widowed ploughman in George Sand’s The Devil’s Pond [1846] is appalled at the idea of finding a new wife three leagues [eight miles] away in “a new pays”.

In 1794 the Abbé Grégoire was compiling a major investigation into the use of the French language and of patois [the derogatory term for all dialects other than the official state idiom]. It was already known that the fringes of France were dominated by quite different languages from French; Basque, Breton, Flemish, and Alsatian. But the two languages that covered the rest of the country – French in the north and Occitan in the south – turned out to be a muddle of incomprehensible dialects. In many parts of France, the dialect changed at the village boundary. His proposals to remedy the situation included building more roads and more canals; wider dissemination of news and agricultural advice; paying special attention to the Celtic and barbaric fringes; and simplifying the French language by abolishing all irregular verbs. A measure that generations of schoolchildren, both French and foreign, would have welcomed !

Barèges, Hautes-Pyrénées

In pre-Revolutionary France, the year was divided into twelve months and two seasons. The season of labour, when even the longest days were too short. And the season of inactivity when life slowed to a crawl. In the Pyrenees when snow was falling or when rain had settled in the men were “as idle as marmots”. In a Pyrenean village like Barèges, close to the Col du Tourmalet. the village was simply abandoned to the snow and reclaimed from the avalanches in late spring. In rural France most farmers had supplementary trades. In 1886, in the little town of Saint-Etienne-d’Orthe, the active population was two hundred and eleven; in addition to working on the land, the population included thirty-three seamstresses and weavers, six carpenters, five fishermen, four innkeepers, three cobblers, two shepherds, two blacksmiths, two millers, two masons, one baker, one rempailleur, and one witch. But no butcher and no storekeeper. Other supplementary occupations included rat catchers with trained ferrets, mole catchers, rebilhous who called out the hours of the night, and “men called tétaires, who performed the function of a breast-pump by sucking mothers’ breasts to start the flow of milk”.

Maps and travellers

In the 1860s Roman roads were still marked on maps, not out of antiquarian interest, but because they were still the best roads available. As the Marquis of Mirabeau remarked in 1756, the Roman roads were built for eternity while “a typical French road could be wrecked within a year by a moderate sized colony of moles”. The dreaded corvée, instituted in 1738, meant that almost the entire male population could be forced to work on road maintenance for up to forty days a year. The system changed with the introduction of cantonniers [road-menders]. Each cantonnier was responsible for about 5 kilometres of road, and was required to be present on the road for twelve hours a day from April to September. The security of the job, and the uniform, were much prized.

Until 1810 the only Alpine crossing for wheeled vehicles was in the far south, over the Col de Tende. Otherwise it was the route taken by Hannibal and his elephants 218 BC. It was with the opening of a new road over the Mont Cenis Pass in 1810 that the cavalcade of sedan chairs, stretchers, and mules was replaced by carts and carriages.

Col de la Tende

In the century after the Revolution, the national road network doubled in size; the canal network grew drastically. There were fourteen miles of railway in 1828, and twenty-two thousand in 1888.

In Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days, Phileas Fogg crosses France in little over a day; he leaves London on Wednesday morning, arrives in Paris on Thursday morning, and arrives in Turin by the Mont Cenis route on Friday morning. And yet parts of France remained unknown. The grandest canyon in Europe, the Gorges de Verdon, were not ‘discovered’ until 1896. It was not until 1906 that the hydrologist Edouard Martel sailed the length of the gorges, and wrote an article in a popular magazine Le Tour du Monde describing their expedition and revealing this ‘American wonder of France’ to the world. This was thirty seven years after John Wesley Powell’s pioneering expedition through the Grand Canyon of Colorado.

Gorges de Verdon

The book is a mass of fascinating, if not always useful, information. When the Tour de France in a burst of publicity routed itself over the mighty Col du Tourmalet in 1910, some people thought the cyclists would be attacked by bears. It is now wrongly thought that the first person to cross the Tournalet on a bicycle was the race leader who arrived at the summit covered in sweat and dust and shouted at the race organisers ‘Assassins’. Graham Robb, himself a keen cyclist, argues that the social impact of the bicycle has been greatly underestimated. He points to a teacher from Chartres setting off by bicycle in 1895 on his thousand-mile holiday.

Col du Tourmalet

Even into the 20th century dog carts were widely used. During the First World War dog carts took machine guns to the front and brought back the wounded. Milk, fruit and vegetables, bread, fish, meat, and letters were all delivered by dog cart. As late as 1925, there were over a thousand dogs in harness in the Loiret department alone. Today city dogs are thought of mainly as an excremental menace; some eight million dogs in France produce eighty tons excrement a day. In the days when manure was highly valued, this was not a major complaint. But today it is !

Charrette-Peugeot

My own discovery of France

My own introduction to France was in the summer of 1961 when my brother and I hitchhiked from Paris to the Mediterranean and back. From Paris to Marseille took us five long days. In Paris we stayed in an UNESCO hostel in the 13ème, in the Boulevard Emile Levasseur, and paid 1,60F. a night for bed and a simple breakfast. Hitchhiking was a stop-start process. Most of the routes nationales were three-lane roads [a lane in the middle for drivers to kill themselves] with plenty of loose chippings and eccentric cambers. Road accidents were a regular occurrence. And the roundabout with an obelisk at Fontainebleau was the elephants’ graveyard for hitchhikers.

The N7 as was

Later, in the mid-1970s, Susie and I lived in the 14ème, on the south side of Paris. It then retained a village-like atmosphere. After we had been away on our summer holidays, to Yugoslavia, several local shopkeepers welcomed us back and asked where we had been. Our landlord was a retired medical doctor from the Yonne, who wore a hairnet and a smoking jacket. We rented an apartment on the first floor belonging to his eldest daughter, who was away in New Orleans. There was a modest garden at the back with a resident hedgehog.

Good Friday 2006

From 2000 to 2013 Susie and I were back in France, further south in the dignified and attractive city of Lyon. Most days we passed by the Confluent where the rivers Rhône and Saône come together. There was a public competition to design the new Musée du Confluent, but it remained a building site for years as the winning entry proved to be unbuildable. On my days off in Lyon I walked regularly in the Monts du Lyonnais, a delightful, peaceful area, all rolling hills and fruit trees. On Good Friday a group from the Lyon Anglican Church invariably walked from Rontalon, stopping for prayers at a trio of wayside crosses, and having lunch in the Café de la Place afterwards. Traditions are easily created !

Good Friday 2013

September 2024

A marvellous contribution – one that all francophiles should read!

Thank you.

LikeLike