Trump’s re-election is a mystery to me and to many European social democrats. [I would say ‘liberals’, but I am no longer sure what the word means.] We all know that he is a a self-obsessed egomaniac. And that he is a serial liar. And that he is a serial abuser of women. And a rather shady businessman. With a strangely orange face. But he also seems to have a very limited understanding of the world and a very limited vocabulary. When Bishop Mariann Edgar Budde challenged him at the traditional service in the national cathedral, asking him to “have mercy on the people in our country who are scared right now”, and on immigrants and on those now threatened with deportation, Trump’s response was that “she’s not a nice person … … not very good at her job”. Which is the language of a peevish five-year-old. The sermon was probably the only critical comment that Trump heard on his first full day in office. And I thought the Bishop should be commended for “‘speaking truth to power’.

Anne Applebaum

Anne Applebaum is an American journalist and historian, born into a reform Jewish family in Washington DC in 1964. She specialises in the history of Communism and in the history of central and eastern Europe. She speaks Russian and Polish as well as English, she is married since 1992 to Radoslaw Sikorski, a Polish politician and cabinet minister [currently Minister for Foreign Affairs], and she has had Polish citizenship since 2013.

I first came across her through her book Gulag: A history of the Soviet prison camps which won a Pulitzer prize in 2004. Gulag traces the history of the camps, beginning with Lenin and the Solokvi prison camp, through the construction of the White Sea canal, to the great expansion of camps under Stalin doing the Second World War. The book looks in detail at the brutal lives and deaths of the inmates; their arrest and interrogation, the all too frequent incidents of starvation and disease, and the circumstances of their deaths. Applebaum draws on the diaries and writings of camp survivors, of whom Solzhenitsyn is the best known. I took the book on holiday to Majorca about 15 years go, and it is a grim read.

After our time in Kyiv in 2021-22 I read Applebaum’s Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine [published in 2017]. It is another grim read. The book tells the story of the Holodomor [literally ‘death by hunger’], also known as the Ukrainian famine, which killed several million Ukrainians in 1933-34. Applebaum contends that the famine was man-made, and that the famine was deliberately engineered by Stalin in order to eradicate the Ukrainian independence movement. [Other historians have argued that the famine was a consequence of the Soviet dash for industrialisation and the over-rapid switch to collective farming.] The book won Applebaum the Duff Cooper prize [for the second time], and contributed to the decision of the European Parliament to label the famine a genocidal act against the people of Ukraine carried out by the Soviet government.

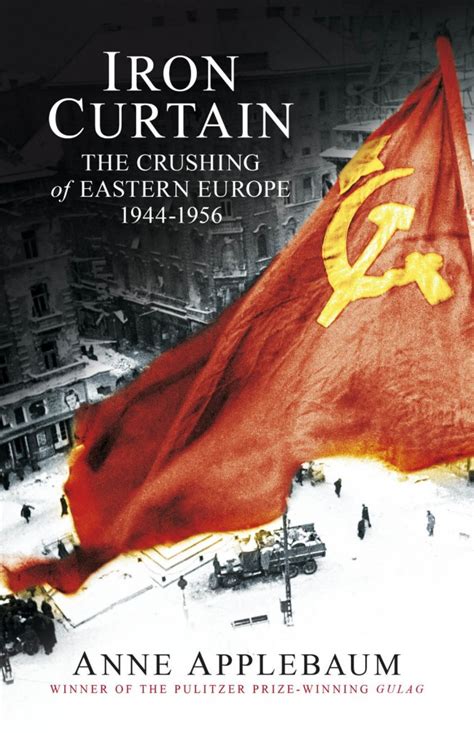

Iron Curtain: the crushing of Eastern Europe

Iron Curtain [published in 2012] is about the crushing of Eastern Europe in the years after the Second World War. A.N. Wilson [not necessarily a reliable guide] says it is “the best work of modern history I have ever read”. The book concentrates on the three countries of Hungary, Poland, and East Germany; very different countries in terms of their economic and political history, but which had all experienced constitutional government and democratic elections.

Applebaum reminds us of the chaos of Eastern Europe in 1945. By the end of the Second War huge armies and vicious secret policemen had marched back and forth across the region, each time bringing political and ethnic changes. The city of Lwów was occupied twice by the Red Army and once by the Wehrmacht. When the war ended it was called L’viv, was no longer in eastern Poland but in the western part of Soviet Ukraine, and the majority of its Polish and Jewish prewar population had been murdered or deported. Stalin and Hitler shared a contempt for the notion of national sovereignty for any of the nations of Eastern Europe, and strove to eliminate their educated elites. Of the 5 and a half million Jews who died in the Holocaust, the vast majority were from Eastern Europe. [Jews were less than 1% of the population of Germany when Hitler came to power in 1933.]

We tend to think of the last phases of the war as a series of liberations. But it certainly didn’t feel like that for the defeated Germans, and especially not for Berliners. Yes, Soviet soldiers opened the gates of Auschwitz-Birkenau and other concentration and extermination camps, and they emptied Gestapo prisons. But Germans remember very well the looting, the arbitrary violence, and the mass rape which followed the arrival of the Red Army. Soviet soldiers were shocked by the [relative] material wealth of Eastern Europe. Liquor and ladies’ clothing, furniture and crockery, bicycles and household linen were stolen from Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and the Baltic states, and shipped back home. No private car was safe. Factories and industrial equipment were systematically dismantled and shipped back east. The Red Army was brutal and powerful. And no Allied Government was in a position to influence what the Red Army did in the occupied lands.

The post-war leaders who emerged in these countries, Ulbricht in East Germany, Bierut in Poland, and Rákosi in Hungary, were all [in the jargon of the time] ‘Moscow communists’, trained in the Soviet Union during the Second World War. By contrast the ‘international Communists’, who had spent the war in western Europe or in North America, were all suspect, as revisionists, or bourgeois deviants, or Trotskyists. But party members who had survived the arrests and purges and confusion of the 1930s now emerged as true fanatics, totally loyal to Stalin and to Soviet policy.

Following on the heels of the Red Army came the creation of a new secret police force, always modelled on the Soviet pattern, the NKVD. Secret policemen were trained in the arts of persuasion, bribery, and blackmail; they convinced wives to spy on their husbands, children to inform on their parents. Military tribunals dealt with suspects, courts without lawyers or witnesses. The Nazi concentration camps at Sachsenhausen and at Buchenwald are now pressed back into service to incarcerate tens of thousands of NKVD prisoners. Prisoners were not systematically killed, but many died because they were ignored and malnourished and forgotten. The Soviet Union promoted ethnic cleansing across the region and there was widespread anti-semitism. Large numbers of Jews emigrated from Eastern Europe to Western Europe and to North America and to Palestine.

The Soviets were totally opposed to the institutions of a civil society. Artistic and cultural groups of all kinds, both for young people and for adults, were banned if they were not affiliated to Communist party organisations. In post-war Warsaw young communists descended on the YMCA and smashed jazz records with hammers. Scouting, which had surprisingly strong roots in Eastern Europe, was looked on with suspicion by the authorities, who sought to diminish its influence by bringing it under state control. Similarly the Hungarian People’s Colleges movement, which sought to promote communal living, democratic decision making, folk dancing and singing in rural Hungary, was destroyed by the authorities. Applebaum notes” “The nascent totalitarian states could not tolerate any competition for their citizens’ passions and talents”.

High Stalinism

By the end of 1948 the Eastern European Communist parties had forced through enormous changes in the new People’s Democracies. They had created from scratch the secret police. And they had eliminated any opposition parties. But the socialist paradise was still far away.

The churches were subject to harassment and worse. But religious leaders remained as a source of alternative moral and spiritual authority. In East Germany the state introduced the Jugenweihe, as a kind of secular equivalent to confirmation services. In Hungary monasteries were closed at short notice. In Poland Catholic elementary schools were progressively phased out. In Hungary Cardinal Mindszenty was arrested and imprisoned. In 1949 Stalin had decreed that the Communist parties should work actively to recruit priests as informers, and to drive a wedge between Catholic churches in the eastern bloc and the Vatican.

Applebaum’s book contains amazing photos of the all-female construction brigade working on the new steel mill at Sztálinvaros – Stalintown. This town was unique in Hungary, but one of several ‘socialist cities’ in the People’s Democracies, each founded around vast new steel mills, part of a comprehensive attempt to jump-start the creation of a true totalitarian civilisation. The design and architecture of the new cities was to reflect a socialist blueprint; there were to be no beggars and no periphery. In spite of high intentions the cities rapidly became lawless slums. Nowa Huta adjacent to Krakow was the first Polish city to be built without a church. In 1959 the Archbishop of Kraków, Cardinal Karol Wojtyla [later Pope John Paul II] celebrated an outdoor mass in a field where he had applied for a church to be constructed. Applebaum sees Nowa Huta as a symbol of the failure of totalitarianism in Poland; “failed planning, failed architecture, a failed utopian dream”.

By 1951 there was no longer anything that resembled an opposition party in eastern Europe; no active opposition, no armed opposition. But there was a passive opposition which took the form of jokes and graffiti and unsigned letters. Youthful discontent was fuelled by American radio, broadcast from Luxembourg or from West Berlin. Teenage rebels, known in Poland as bikiniarze, developed a taste for jazz and an envy of American consumerism. Between 1948 and 1961 an estimated three million people [out of a population of 18 million] left East Germany for the West. Many of them because they thought they could make more money.

In the fullness of time Stalin died – in March 1953. A subsequent revolution in Berlin was brutally suppressed with Soviet troops and T-34 tanks. Three years later an uprising in Budapest provoked a second Soviet invasion. But the suppression of the rebellion led to a significant change in the perception of the Soviet Union by Western Communist parties and their sympathisers. The French Communist party fractured, the Italian party broke with Moscow, and the British party lost most of its members. Any lingering rose-tinted view of the Soviet Union was over.

Envoi

Yes, it’s all history now. But some questions remain. Why did the socialist system produce such dire economic results ? Why was the Communist propaganda so unconvincing ? Might more liberal measures have prevented the [eventual] revolutions of 1953 and 1956 ?

And there are lessons to be learned. In February 1956, Nikita Krushchev stood before the 20th Party Congress and denounced the ‘cult of personality’ which had surrounded the late Stalin:

“it is impermissible and foreign to the spirit of Marxism-Leninism to elevate one person, to transform him into a superman possessing supernatural characteristics, akin to those of a god. Such a man supposedly knows everything, sees everything, thinks for everyone, can do anything, is infallible in his behaviour. Such a belief about a man … was cultivated among us for many years”.

The speech literally killed Bleslaw Bierut, the Polish leader who was present at the Congress, and died there of a stroke or heart attack, presumably brought on by shock.

In an age of resurgent demagogues, we would do well to heed this warning against the cult of personality. [Think Trump and what some wit has labelled the Nerd Reich.] And we need to learn to value both the democratic process, and the institutions of civil society which serve as a defence against totalitarian regimes. Whether of left or of right.

February 2024