The amaryllis on the dining table has come out in a big way. And we’ve been out too; we took a Car Club car out along the coast in East Lothian. I couldn’t get my left leg under the steering wheel, so Susie had to drive. After a standard trip to the charity shop, we drove out to Gullane and walked by the sea and had a picnic on Goose Green in glorious sunshine. And then returned via Haddington.

Canon W.H. Vanstone

W.H. [Bill] Vanstone, born in 1923, was the product of an English vicarage. His father was vicar of a working-class parish in an industrial Lancashire town, and his mother was in effect the unpaid parish worker. As he later wrote, their wholehearted commitment to the church could either have inspired him or alienated him. As things turned out they were the model for his own ministry. After taking two Firsts at Balliol in the immediate post-war years, he trained for ordination at Westcott House [a starred First in the Cambridge Tripos] and at General Theological Seminary, New York. He was ordained in 1950. Vanstone was said to be one of the most academically gifted ordinands of his generation, and Oxbridge colleges were keen to recruit him. But, following in his father’s footsteps, he served in two working-class parishes in Lancashire for the next three decades. After a heart attack in 1978 he was persuaded to become a Residentiary Canon at Chester Cathedral, where he remained until his retirement in 1991. He died in Cirencester in 1999.

In both his Lancashire parishes, Vanstone established a strong reputation through boys’ clubs, and oversaw a celebrated series of summer camps in Wales and in the Western Isles of Scotland. In a camp on Coll the boys went to the Wee Frees in the morning and the Church of Scotland in the evening. There had been a severe storm the previous night, and this was the focus of the Sunday sermons. The Wee Free minister saw the storm as a sign of God’s judgement on sinful men. The Church of Scotland minister emphasised the loving care of Jesus the Good Shepherd. Vanstone and his lads agreed that the latter homily was both shorter and more Christian ! In both his parishes Vanstone made long-lasting friendships, promoted the discipline of regular Sunday worship, and encouraged many men into ordination.

The latter part of his ministry was different. Vanstone’s colleagues at Chester were puzzled by him, and although he loved cathedral worship and gave much appreciated homilies, he clearly found teamwork difficult. He was averse to changes in routine or worship, and unenthusiastic about both liturgical reform and about the changing role of laity following the Second Vatican Council. As his obituary in the Independent noted, he was quick to find reasons to ‘leave well alone’. He is remembered today, if at all, for two slim theological books published in the 1970s and the 1980s.

Love’s Endeavour, Love’s Expense

My copy of this book suggests that I started to read it in Duns in the 1990s but didn’t finish it. Love’s Endeavour, Love’s Expense starts with Vanstone contemplating his new parish. He is going to a new housing estate where there is no church building. He visits the new district and he wonders why so few people show any interest in the new church project. What, he asks, is the purpose of the church ? And he answers the question not in missiological or in sociological terms, as I might have attempted, but in theological terms. He decides that the key question is: How might people respond to the love of God ? [I guess that in the 1990s I found the following chapters, The Phenomenology of Love and The Kenosis of God a bit difficult to grasp..]

Vanstone explores the nature and the cost of authentic love, ‘broader than the measure of man’s mind’. False love is love that lays down limits or conditions; it is love which seeks to maintain an element of control; it is love which is offered with an air of detachment. By contrast authentic love is limitless, and it is precarious, and it is vulnerable. This is the nature of God’s love.

We are wrong to see God’s work in creation as serene and effortless activity. God’s love is costly, an emptying of himself, a refusal to abandon those who suffer and die. [He instances the children who died at Aberfan.] God’s love does not demand recognition. But rather it awaits a creative response. “Thus we may say that the creativity of God is dependent, for the completion and triumph of its work, upon the emergence of a responsive creativity … … That by which, or in which, the love of God is celebrated may be called the Church”. The supreme task of the church is to enable men and women to respond to the love of God in their lives.

The book won the Collins Biennial Religious Book Award in 1979. As Harry Williams wrote in a foreword, it is a book based on many years of parish experience, of Vanstone’s wrestling with God. The book ends with a wonderful hymn which I have never heard sung.

Morning glory, starlit sky

1. Morning glory, starlit sky,

soaring music, scholar’s truth,

flight of swallows, autumn leaves,

memory’s treasure, grace of youth.

2. Open are the gifts of God,

gifts of love to mind and sense;

hidden is love’s agony,

love’s endeavour, love’s expense

3. Love that gives, gives ever more,

gives with zeal with eager hands,

spares not, keeps not, all outpours,

ventures all, its all expends.

4. Drained is love in making full,

bound in setting others free,

poor in making many rich,

weak in giving power to be.

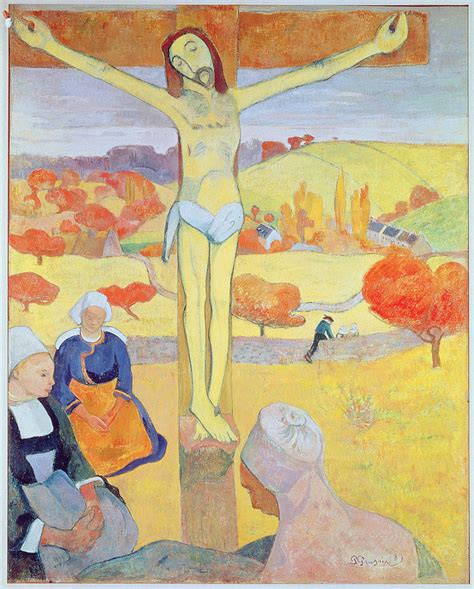

5. Therefore he who shows us God

helpless hangs upon the tree;

and the nail and crown of thorns

tell of what God’s love must be.

6. Here is God: no monarch he,

throned in easy state to reign;

here is God, whose arms of love,

aching, spent, the world sustain.

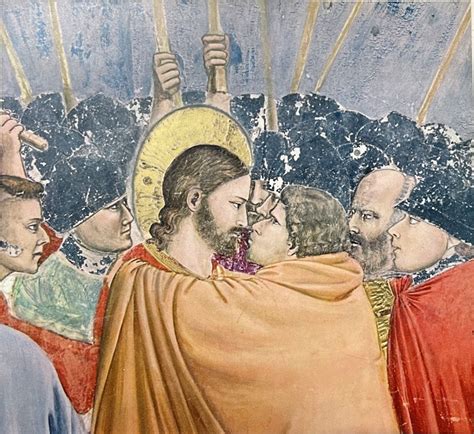

The Stature of Waiting

Vanstone’s second book is perhaps more accessible. He starts with the Passion Story, and argues [he was a classical scholar] that the Greek verb describing Judas’s action is mis-translated. Jesus was handed over, rather than betrayed. Crucially in both Mark’s and John’s gospels, from his arrest in the garden of Gethsemane Jesus ceases to be in charge; instead of being the subject of verbs, he is the object. He becomes a person to whom things are done by other people. He moves from action to passion; from acting in freedom to waiting on the decisions and actions of others.

This leads Vanstone into a lengthy reflection on the status of a patient. Perhaps someone who is suddenly cut down by a serious accident or a debilitating illness. Or by retirement ? But we are easily embarrassed and ashamed of being dependent on others; of not being in charge of our lives. Thus many retired people are anxious to tell people they are now “busier than ever”. Retirement can be thought acceptable. But unemployment can be seen as degrading.

Vanstone is concerned to reject the identification of work and self value. He points to a bed-ridden mother of five children, almost wholly dependent on her neighbours, whose helplessness created a social effect that other agencies had tried in vain to achieve. He suggests that we model ourselves on God whom we wrongly perceive as all action, always the subject and never the object. But this is the wrong model. “The long-taught Christian doctrines of the image of God in man and the impassibility of God do seem to imply … … that the role in the world that is uniquely appropriate to man is the role of active subject, of initiator, creator, and achiever; and that in the opposite role of patient, of recipient, of dependent object man falls below his proper stature and status and dignity”.

The climax of Jesus’s life, Vanstone argues, is the Passion rather than the Crucifixion. In ‘handing himself over’ Jesus discloses a free activity of God which culminates in the surrender of freedom. A state where he must wait on the deeds and decisions of men. So too for us. In loving we commit ourselves to waiting on others. Vanstone offers us an example from Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment: Sonia Marmeladov follows Raskolnikov to a Siberian prison camp and waits for him by the prison fence. When she falls ill and fails to appear, Raskolnikov loiters by the fence and as he waits for Sonia realises that he loves her.

Waiting is not a degraded condition. Although it can lead to frustration, it can also be both caring and productive. The glory of God is revealed in the waiting figure in Gethsemane. He is not diminished but invested with enormous dignity. And we too must wait with God, handed over to the world to receive its meaning, its beauty and squalor, its good and evil.

Envoi

The Stature of Waiting is an appropriate book for someone who is retired and waiting, almost patiently, for hip surgery. If there is a biography of Vanstone, I am not aware of it. It seems that he was an elusive man, not universally liked. His slim books, though a bit dated and a bit repetitive, are a corrective to the unfocused activism that sometimes passes for Christian ministry. I was intrigued to read that, according to David Wyatt’s obituary notice in the Church Times, Jürgen Moltmann apparently said that “Love’s Endeavour, Love’s Expense is the book I’d most like to have written had I still been a pastor in the Lutheran Church.” Robert Runcie was a lifelong friend who preached at Vanstone’s funeral. According to Humphrey Carpenter, he greatly admired Vanstone, saying he was the priest that Runcie would like to have been.

There is a third and final book by Vanstone, Fare Well in Christ, published in 1997, which I shall now try and track down. Meanwhile the garden needs some attention. The grass needs cutting. And we are trying to organise some kind of celebration for the summer to mark the passing years.

April 2025