So, President Trump’s five-day golfing holiday here has come to an end. For his round at his Trump Turnberry course he seemed to be accompanied by an extraordinary number of golf buggies including possibly the world’s only armour-plated buggy, presumably a precaution against another assassination attempt. There were very few actual shots of his golf. Word is that he cheats at golf as in many other things. At one golf course he was known as Pele, a reference to his regularly kicking his ball back onto the fairway to a more favourable lie. His bulk and his headwear make him look increasingly like Robert Maxwell, another galloping crook. [Though Maxwell to his credit spoke half a dozen languages well. And, unlike Trump, inherited no money from his father.]

Trump and Keir Starmer are polar opposites in many ways. But I guess we should be grateful that they seem to have forged a decent working relationship. Which might help ramp up pressure on Trump as regards what is happening in Gaza. [And in Ukraine.] I can hardly bring myself to watch the television news from Gaza. I wrote a somewhat intemperate letter to the Church Times a week ago, criticising General Synod, and the House of Bishops, and the UK government for their pusillanimous response to what Israel and the IDF have been doing for many months. Glyn Paflin e-mailed me to check on my postal address. But they didn’t publish the letter. Disappointing.

Madeleine Bunting: The Model Occupation

One of the more interesting books that I was given for my birthday is Madeleine Bunting’s The Model Occupation: The Channel Islands under German Rule. Bunting, born in 1964, studied History at Cambridge and at Harvard, and then joined The Guardian where she worked as a news reporter, leader writer, religious affairs editor, and columnist. She is the author of five books of non-fiction and two novels. The Model Occupation, first published in 1995, was her first book.

German troops arrived on the Channel Islands in June 1940, a few days after the fall of France. Two British battalions had been withdrawn a week or two earlier. It had seemingly been assumed by the British authorities that the war would not reach the islands, and the German troops disembarked from their troopships unopposed. Preparations made by the German High Command in France for a battle for the islands proved unnecessary. Contrary to expectations, the German troops were received with polite deference by the islanders. Numbers were small initially, but by Christmas 1940 there were roughly two thousand Germans on Jersey and a similar number on Guernsey.

This was to be a model occupation, The cordial relations between the German commander and the island authorities were matched by the polite helpfulness of the islanders and the law-abiding soldiers. It soon became apparent that there was no need for German soldiers to carry weapons or to wear a steel helmet. After the fighting in Poland, and the Low Countries, and in France, and the tense expectation of an imminent invasion of England, the Channel Islands must have seemed like a holiday camp to the Germans. They enjoyed the white beaches and the bright blue sea. At the beginning there was plenty of food, and the shops were stocked with goods long unobtainable back in Germany – stockings, shoes, make-up, chocolates – to send home to loved ones. The island shop-keepers, glad of the custom, accepted their Reichsmarks happily enough.

But it was an occupation nonetheless. The bailiffs of the islands had instructions from London to take over the civil administration, co-ordinating with the German military authorities, while trying to ensure that their actions were in accordance with the Hague conventions. But to some people the bailiffs’ actions seemed more like collaboration. And some of their measures are disturbing. When some islanders painted V for Victory graffiti on road signs across the islands, the bailiff offered a £25 reward for information leading to a conviction. And when two German soldiers were killed in a modest British raid on the islands, the bailiffs agreed to supply a list of the names of two hundred British-born islanders, who were subsequently deported to internment camps in France and Germany. From 1941 came a series of anti-Jewish measures. Which included the forced registration of all Jewish residents of the islands. Three Jewish women were deported from Guernsey in January 1942 and all three died in Auschwitz.

The book received glowing reviews on publication. Hugh Trevor-Roper wrote, in the Sunday Telegraph, that it is “a masterly work of profound research and reflection, objective and humane”. [I am a bit surprised that anyone took Trevor-Roper seriously in 1995 after he had, in 1983, as a director of The Times, rushed to authenticate the forged Hitler Diaries, which the Sunday Times had paid good money to serialise. A misjudgement that caused Private Eye to refer to him as Hugh Very-Ropey. Or Lord Facre.] Norman Stone wrote in The Times, “Madeleine Bunting is a superb chronicler of what happened … if you want a classic example of the dilemma of resistance, here it is”. But the book was highly controversial, and provoked a furious controversy on the islands, where some critics thought it was inappropriate to dig up details of what looked like a shameful past. In her Epilogue Bunting acknowledges that the story sits uneasily alongside the preferred, Churchillian post-War image of Britain as a country fighting alone ‘on the beaches and on the landing grounds’. The islands’ experience contradicted Britain’s complacent assumptions about the distinctiveness of the British from the rest of Europe. Under occupation the British had behaved much as the French, the Dutch, or the Danish.

Perhaps the saddest story concerns the fate of the several thousand slave labourers, Russian, Ukrainian, North Africans and Spanish Republicans, who were brought to camps on Alderney. About sixteen thousand prisoners were brought to the islands to work on the fortifications, and they lived and worked, and died, under appalling conditions. Bunting traces some of the Russian survivors who made it back with great difficulty to their home villages. Where as ‘repatriates’ they were accused of collaborating with the Germans and treated as traitors. Some were imprisoned in Stalinist camps and other conscripted into labour battalions.

It is an interesting and controversial book by a gifted writer.

Francis Beckett: Stalin’s British Victims

Earlier in the month, when I was still only in my seventies, I read this book by Francis Beckett.

In the 1920s and 1930s there were several hundred British and foreign communists living in Moscow. Among them was Bill Rust, a Communist journalist and subsequent editor of the Daily Worker, who moved there in 1928 to work for the Comintern. Beckett tells the story [the book was published in 2004] of four women who were victims of Stalin’s grim purges. Rose Cohen, born in 1894, was the daughter of Polish immigrants in the East End. She worked for the Labour Research Department under Beatrice and Sidney Webb, was a suffragette, a feminist, and a founder member of the British Communist party. She was beautiful [the love of Harry Pollitt’s life; he proposed to her on numerous occasions], but in 1920 she married Max Petrovsky, a Ukrainian Jew who worked for the Comintern. From 1927 they moved to Moscow. Cohen and Petrovsky both worked for the Comintern and for the Moscow Daily News, and were considered a golden couple by the expatriate community in Moscow. But Petrovsky disappeared in April 1937 and was shot later that year. Rose was arrested in August 1937 and shot in November. It was only in 1956, after the death of Stalin, that Cohen’s fate became known. And she was posthumously rehabilitated.

Rosa Rust, Bill’s daughter by his first wife, was abandoned in Moscow; and was caught up in the ethnic cleansing of the Volga Germans, spending time in a forced labour camp. She eventually escaped from a copper mine in Kazakhstan in 1943, and was repatriated to Britain with the help of Georgi Dimitrov. In England she first learned English, and then worked for Tass, the Russian news agency as a translator, and married George Thornton, a young communist historian. She and her husband lived happily in Yorkshire for fifty years sharing a love of drama and poetry, and cricket, and walking by the sea. She died in 2000, still speaking English with a strong Russian accent.

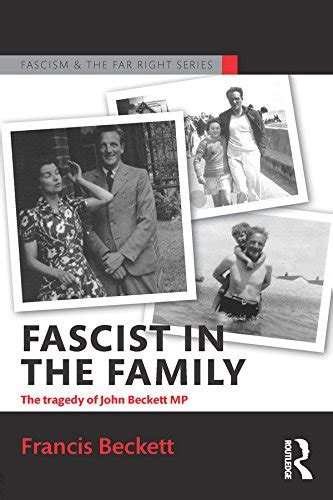

Beckett’s story is equally fascinating. His father, John Beckett, was a Labour MP from 1924 to 1931. But he was strongly opposed to Ramsay MacDonald’s National Government, and joined Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists, where he served as editor of the publications Action and Blackshirt. During the Second War he was interned in Brixton and on the Isle of Man, clashed with other BUF members and converted to Catholicism. Francis Beckett’s book on his father, The Rebel who lost his Cause – The Tragedy of John Beckett MP, was punished in 1999. Arguably another casualty of the 1930s.

Envoi

We have friends coming, from Gloucestershire and from Lyon, in the next few weeks. The grass needs cutting. And I am hobbling around, hoping to advance an appointment with a hip consultant. At present that first consultation still looks to be 32 weeks away, which will take us to January/February next year. Susie and I are looking with interest at the website of the Nord Orthopaedics Institute in Vilnius, Lithuania. Watch this space.

July 2025