As a change from reading books about the Spanish Civil War, we had an occasional outing in a Car Club car. Susie drove, as I can’t get my left leg under the steering wheel. We took garden rubbish to the recycling centre, bought Green Goddess compost from Caledonian Recycling, and some inexpensive wine from ALDI. Mainly Viognier and South African sauvignon blanc. And then we drove down to the cafe at Cockenzie House for lunch, the world’s biggest sandwich. And had a little walk along by the sea to Port Seton.

The International Brigades

“Many have heard it on remote peninsulas,

On sleepy plains, in the aberrant fisherman’s islands,

In the corrupt heart of the city,

Have heard and migrated like gulls or the seeds of a flower

They clung like burrs to the long expresses that lurch

Though the unjust lands, through the night, through the alpine tunnel;

They floated over the oceans;

The walked the passes: they came to present their lives.”

W.H. Auden

I guess it was the International Brigades that first drew my attention to the Spanish Civil War. Specifically I think it was Julian Symons book on The Thirties, which I read at school, and then Jessica Mitford’s very readable Hons and Rebels. Jessica Mitford, always known as Decca, was the second youngest of the celebrated Mitford sisters. Partly as a reaction to her fascist-leaning sister Unity, known as Boud, she carved hammer and sickle emblems on the windows of the family home. In early 1937 she eloped with her second cousin, Esmond Romilly, a nephew of Winston Churchill, public school rebel and schoolboy editor of Out of Bounds. They were married at Bayonne. Romilly had made his way to Spain the previous year and had fought with the nascent International Brigades in the defence of Madrid and at the battle of Boadilla.

Jessica ‘Decca’ Mitford and Esmond Romilly

Vincent Brome: The International Brigades

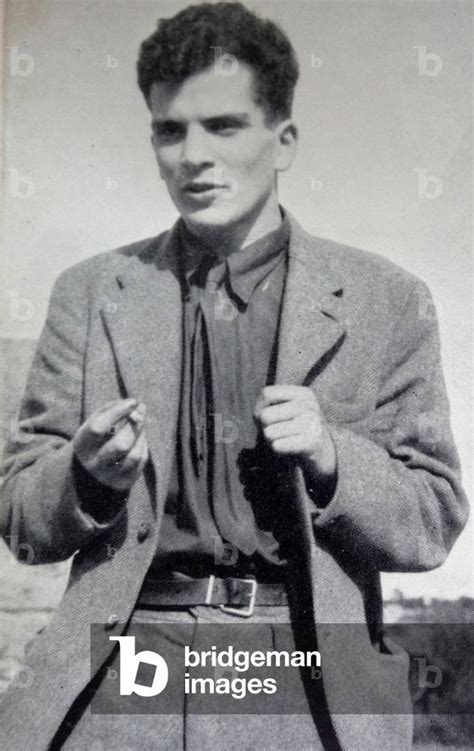

Esmond Romilly and John Cornford, characterised by Val Cunningham as “two public school bruisers” both feature prominently in Vincent Brome’s book, which [published in 1965] claimed to be the first comprehensive history of the International Brigades. [John Cornford, Cambridge educated poet and communist, was killed in December 1936 fighting at Lopera near Cordoba. Esmond Romilly survived Spain, returned to London later in 1937 to work as a croupier and as a copywriter, emigrated with Jessica to the United States in 1939, and was killed in November 1941 flying as an observer with the Royal Canadian Air Force.]

John Cornford

The Brigades, Brome explains, were composed of thousands of volunteers who came, more or less spontaneously, from a variety of countries to fight against Franco’s Nationalist rebels. Several people are credited with the originating the idea of the International Brigades; Thorez, the leader of the French Communist Party; Tom Wintringham, who was in Spain with a British medical unit; Dimitrov, the Bulgarian head of the Comintern. Early volunteers, including many Eastern Europeans who had been expelled from their own countries for revolutionary activities, were organised to travel via Paris. Josip Broz [later Marshal Tito] was at the main Brigade offices in rue Lafayette. In Britain there were recruitment centres at the Communist Party HQ in King Street, and at a cafe in the Mile End Road. Groups were escorted across Paris to nondescript hotels. Sometimes in French berets and dungarees. British and Americans were in the minority. Volunteers came from Germany, France, Italy, Poland, Ireland, Mexico, Latvia, and Yugoslavia. Groups travelled south by train, and were escorted in groups across the mountainous Pyrenees.

The first significant action of the Brigades was the Battle for Madrid which began in November 1936. The city was threatened by the Nationalist advance from the west. Then arrived the XIth International Brigade, roughly 2,000 men, predominantly German, French, and Belgian. Including John Cornford. “Here in Madrid is the universe frontier that separates Liberty and slavery. It is here in Madrid that two incompatible civilisations undertake their great struggle: love against hate, peace against war, the fraternity of Christ against the tyranny of the Church … … This Madrid. It is fighting for Spain, for Humanity, for Justice …” declared Madrid Radio. Later in November the hastily assembled XIIth Brigade arrived. Including Esmond Romilly. The Brigades were successful at a cost in holding the Nationalists in the battle for the university city.

The British battalion went into action at Christmas 1936. Its leaders included George Nathan, a former British army officer, who had been the only Jewish officer in the Brigade of Guards; Fred Copeman, a former seaman who had been one of the leaders of the Invergordon Mutiny; Wilf Macartney, the first commander of the British battalion; to be succeeded by Tom Wintringham. In early 1937 the Nationalists made successive attempts to encircle Madrid and cut its major access roads.

Brome offers a broad narrative of the military involvement of the Brigades. They fought at Las Rozas on the Madrid-Corunna road in January 1937. The British Battalion were heavily involved in the Battle of Jarama, in February 1937. Both sides lost about 20,000 men. With the International Brigades being hardest hit. Both sides claimed victory. The Madrid-Valencia road remained in Republican hands. Later in 1937 the Brigades fought at Brunete, where George Nathan was killed by a bomb; and then on the Aragon front around Belchite. Where Hemingway visited them.

Volunteers could not be expected to conform to the disciplinary standards of a regular army. Many Brigaders clamoured to be released from service. But requests were invariably turned down. Stephen Spender visited Spain in 1937 to try and secure the release of his friend Jimmy Younger, who had joined the Communist party and volunteered under Spender’s influence. Deserters from the Brigades suffered re-education and were occasionally shot. Brigaders were not allowed to go home in case they spread stories of widespread dissatisfaction.

From 1937 there were numerous political conspiracies between Communists, Socialists, and Anarchists. In November 1937 the Brigades were formally incorporated into the Spanish army. Brigaders were encouraged to improve their dress and appearance, to learn Spanish, and to salute officers. Not all of which was appreciated.

After their defeat and terrible losses in the winter fighting at Teruel, the Republicans decided in July 1938 to attack across the river Ebro, to restore communication between Catalonia and the rest of republican Spain. In spite of early successes, the attack was a failure.

The battle of the Ebro

As the battle of the Ebro approached its grim climax, there was an announcement that the International Brigades were to be withdrawn. In part a decision of the Non-Intervention Committee. On October 17th, 1938, reckoned to be the second anniversary of the International Brigades, there was a big parade in Albacete. Followed in November by a great farewell parade on Barcelona. The Communist La Pasionaria made a speech: “Comrades … You can go proudly. You are history. You are legend. You are the heroic example of democracy’s solidarity and universality. We shall not forget you …” The League of Nations Commission calculated that there were 12,673 volunteers in the Republican forces from twenty nine countries. Roughly half of them were repatriated by January 1939. When the Republic collapsed many of the remaining International Brigaders fled across the border in France. Some 5,000 Brigaders were held in basic camps round Argeles and Saint-Cyprien with inadequate water supplies and no sanitation. The Germans and Italians had no homeland to go to. Some made their way to Mexico. Others to North Africa.

Brome’s book is a good read. I was found a second-hand copy a few years ago, sold off by a college library in Aberdeen. But in truth the book is based on a rather thin set of sources, almost entirely in English, and it deals really only with the British and American brigaders. There are other books, newer and, I hope, better, which I will get down to looking at in the coming weeks.

William Rust: Britons in Spain

Bill Rust was the Daily Worker’s correspondent with the International Brigades in 1936-38. [He subsequently became Editor of the Daily Worker from 1939 to 1949, when he died of a heart attack at the age of 45.] His book on the Brigades offers a sketchy narrative history of the British Battalion of the XVth Brigade, majoring on Jarama, Teruel, and the Ebro, with an incomplete Roll of Honour. The book was written before the end of the Civil War, follows the [Communist] Party Line, and minimises the in-fighting among the Republicans. The book ends with the tumultuous welcome of some 300 Brigaders at Victoria station in December 1938.

Bill Alexander: British Volunteers for Liberty: Spain 1936-39

Bill Alexander [born in 1910] was a lifelong Communist and political activist. After doing chemistry at Reading University, he became an industrial chemist. He volunteered for the International Brigades in 1937, and fought with the British Battalion at Brunete and at Teruel. He commanded the British Brigade at the start of the Battle of the Ebro, but was badly wounded and invalided home in June 1938. He fought in North Africa during the Second World war, and then worked as a full-time organiser for the CPGB. His book on the British volunteers was published in 1982, some fifty years after the war. The book is published by Lawrence and Wishart [like Bill Rust’s book], and follows the Communist party line. It is straightforward narrative history. He is very critical of the inadequate trenches of the Anarchists. The book contains a Roll of Honour of 526 volunteers who died in Spain. Mainly rank and file. In a final chapter, he asks ‘Was it all worthwhile ?’ And echoes La Pasionaria: ‘Better to die on your feet than to live for ever on your knees’.

A first trip to Spain

Our trip was conceived in the Museum Tavern, across the road from where I worked as a commissioning editor at George Allen & Unwin, down the street from the British Museum. This is the very early 1970s. David hadn’t been away on any summer holiday. And nor had I. He had an igloo-shaped, two man tent, with inflatable tent poles. I had a company car, a Monza Red Fiat 124. [Chosen by me instead of the standard company Cortina. It was a bad choice. The gear box collapsed within a year. And the job collapsed not very long afterwards.] So off we went.

The Museum Tavern

We crossed via Newhaven-Dieppe and headed south for the sunny Mediterranean. I did all the driving, and David sat in the passenger seat complaining of toothache.Our first night was in a Relais-Routiers somewhere south of Bordeaux. The food was OK, but the hotel next to the main road was very noisy. Our first night in Spain was at San Sebastian. There might have been a beautiful view from the campsite. But it rained all night, and in the morning there was a heavy, clinging sea mist. Like an Edinburgh haar, but more so. We were obviously on the wrong side of the country. As we crossed Spain, we spent a night at Huesca. Where there was an unsuccessful, predominantly anarchist offensive in June 1937. George Orwell fought there with POUM. He was shot in the neck and scarred for life, but survived.We didn’t see him. But we did spend the evening with a bunch of Australian girls. All unaccountably called Frecks.

Mequinenza

The next day we passed through Mequinenza, on the borders of Aragon and Catalonia. There had been fierce fighting there during the Battle of the Ebro in 1938, and it looked as if nothing had happened there since. Nothing moved. We reached the Med somewhere near the Ebro estuary, grey clouds and a grey sea. After a couple of days camping in Peniscola, mainly spent drinking cuba librés and reading Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano, I developed a recurrence of a pilonidal abscess. David as a onetime medical student cautioned against Spanish surgeons. “You don’t know where their scalpels have been.” We drove home through Barcelona. The cafe where we ordered omelettes gave us doughnuts. We didn’t have the language to complain. A couple of days later we limped back into London. I booked into the Nelson Hospital to have my abscess drained. While David, whose toothache was now miraculously cured, went climbing in North Wales.

Peniscola

September 2025

Forget the Civil War for a moment – I am hungry for sandwiches!

LikeLike