Autumn is here

Late windfall apples and leaves are down in the garden. It gets light later and dark earlier. And we are constantly tempted to override the heating soon after lunch. The fragile peace in Gaza is still holding. Thank God ! A reproach to people like me that doubted whether anything good could come from a meeting between Trump and Netanyahu. A new Archbishop of Canterbury has emerged. Her great strength may be that she is not an Old Etonian. If the church was determined to appoint a woman, then I think that either the bishop of Chelmsford or the bishop of Gloucester would have been a more exciting appointment. I don’t doubt that Dame Sarah Mullally will nail her colours firmly to the middle of the road. And that may not be wholly a bad thing.

Sunny Sunday lunch at the Prestonfield House hotel

Travelling

When I was growing up we never went abroad as a family. Holidays were spent with my grand-parents, first at Minety, between Swindon and Cheltenham, where my maternal grandfather was the station master on the GWR, and then after he retired at Bradford-on-Avon. Which in the 1950s and 1960s was a magical place with a Saxon church, and a chapel on the bridge, and a medieval tithe barn. And the river Avon and the canal. And lots of honey-coloured houses and not many people.

Bradford on Avon

I didn’t go abroad until Paul and I went to France in 1961. I was just sixteen, and we spent a week in a UNESCO hostel in Paris, in the 13ème, and then hitchhiked down to the Med and back. The whole three weeks was a revelation. Though we came back tired and hungry. And I think Paul had picked up a flea in the youth hostel at Fontainebleau. We were away for exactly 3 weeks. And it cost us £15 each. At a time when there were between 12 and 13 francs to the pound.

For a few years after that I kept a list of the countries I had visited. Initially France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, and Switzerland. A few years later I hitched to Istanbul, and added Yugoslavia, as was, and Bulgaria and Turkey to the list. And made a point of hitching back via Italy, as a girl I knew was doing a course in Perugia, and made a detour to take in San Marino. In subsequent years I haven’t added greatly to the list. Though in the past decade we have made a first trip to the United States, wonderful but never again, and to Ukraine. Which we left six weeks before the Russian troops invaded.

In the past 18 months I’ve scarcely travelled out of Edinburgh. Apart from the Men’s Retreat down at Maresdous last autumn. Any travelling has been vicarious through a variety of books. In past weeks I’ve been frequently in Spain, with the International Brigades in the Jarama Valley. And then a few days travelling the length of the river Amur, the longest river in the world that I had never heard of. My companion along the river was Colin Thubron, much the same age as me, and author of a shelf of travel books mainly set along the Silk Road and in the former Soviet Union. The secret source of the river is in the Mongolian mountains, close to the birthplace of Genghis Khan, ruler of the biggest contiguous land empire in history. For much of its length the river is the border between Russia and China, traditional enemies who dislike and distrust each other. And it eventually it empties into the Okhotsk Sea opposite Sakhalin island. But – in ten days time we shall be travelling ourselves, and breaking new ground for us, to Lithuania.

River Amur

Richard Baxell: Unlikely Warriors

Continuing my looking back at the Spanish Civil War, I have been reading Richard Baxell’s book, Unlikely Warriors: the British in the Spanish Civil War in the Struggle against Fascism. This is a big book by an academic historian, based on a PhD thesis supervised by Paul Preston at the LSE. It reads a bit like a doctoral thesis, and runs to 450 pages and to more than 2,000 footnotes. When it came out in 2015 it was the most recent and fullest account of the British who fought in Spain. [Spoiler alert: there is now a more recent book, sitting unread on my shelves.]

British Union of Fascists

The early chapters of Baxell’s book set the context in the UK with polarised politics and a desire to defeat the [Mosleyite] Blackshirts. The book reminds us that those who volunteered for Spain were motivated as much by concern about what was happening in the UK as they were about the rise of Hitler and Mussolini. From 1933 onwards members of the Labour movement and trade unionists increasingly involved themselves in anti-Fascist demonstrations. Walter Gregory, who became a company commander in Spain, was injured while disrupting a British Union of Fascists meeting in Nottingham. George Watters, who fought with the British battalion at Jarama, was involved in anti-Mosley demonstrations in Edinburgh. The biggest concentration of Jews in pre-war Britain was in London’s East End; and a number of those who fought in the Brigades were involved in countering the big Mosleyite march in East London in October 1936, the Battle of Cable Street.

The Battle of Cable Street, 1936

Baxell offers a detailed narrative of the history of the International Brigades: their early, crucial role in the defence of Madrid in December 1936; the long, bloody slog at Jarama, in February-March 1937; the fighting in bitter winter conditions at Teruel, December 1937 to January 1938; and the final costly fighting around the Ebro in the summer of 1938. The story is well told, though more maps would have been helpful for the reader Their last action, on the Ebro near Gandesa, was as bloody as any that the British Battalion had fought. All that followed was a final emotional farewell parade in the streets of Barcelona in October 1938 in front of a huge, cheering crowd.

The closing chapters of the book tell the story of what happened next for the Brigaders. Baxell notes that some remained in Nationalist prisons until after the end of the war. When they returned home many who had served in Spain were systematically excluded from joining the armed forces. John Longstaff, who resigned from his job as an engineer to join up, was told by the colonel in charge of recruitment “we are under instruction not to recruit anyone who fought with the International Brigade.” Likewise James Maley and John Peet, who both volunteered for the RAF, were both rejected because of their time in Spain. The policy was apparently put in place by MI5 in January 1939.

Bernard Knox, an American working with the French resistance in Brittany was told by senior officers, “you were a premature anti-Fascist.” Tom Wintringham, the ‘English Captain’, called repeatedly for the creation of a citizens’ army; and set up a guerrilla training school in Osterley in west London, where the instructors included former Brigaders. [I bought a Penguin Special on Guerilla Warfare by Bert ‘Yank’ Levy, a machine gunner in the British Battalion, in a charity shop in Morningside of all places a couple of years ago.] Originally a private enterprise it was later taken over by the War Office. There is evidence that some of those who fought in Spain were recruited as Communist spies. Alexander Foote, a driver and courier in Spain, was recruited as a Red Army intelligence agent in Switzerland.

Malcom Dunbar, the Cambridge educated and very capable Chief of Staff for the Fifteenth Brigade, was drafted into the army as a private and never rose above the rank of sergeant. But Bill Alexander was recommended for officer training at Sandhurst, and served with distinction in North Africa, Italy, and Germany. The gifted linguist David Crook, though a known member of the Communist party, was interviewed [in French, Spanish, and German] by the RAF, and promptly offered an Intelligence job in the Far East. Those who served as doctors with the International Brigades were almost universally welcomed into the British Army. And sought to apply lessons learnt in Spain.

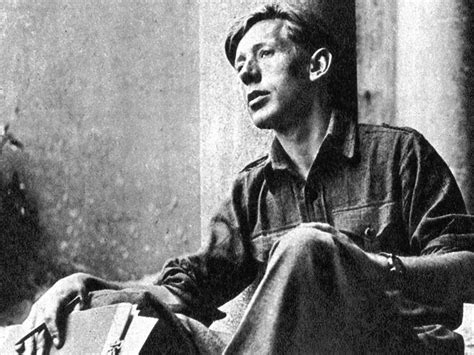

James Robertson Justice

Bernard Knox returned to Harvard, took his doctorate on Greek narrative tragedy, and became Director of Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies. Nathan Clark, of the Clark’s Shoes family, invented the ubiquitous desert boot, supposedly based on the footwear he had observed while serving in Spain as an ambulance driver. Regardless of his record in Spain James Robertson Justice became one of the best-known faces of the British cinema in the 1960s and 1970s. Laurie Lee’s death in 1997 provoked a vigorous debate as whether he had ever fought with the International Brigade. There is evidence that he did serve in the Brigade, but his writings about his time in Spain are thought to be largely fictional. The death of Jack Jones, the powerful trade union leader, in 2009 revived the accusation that he had been a Communist agent. The accusation is unproven.

Laurie Lee

Cardiff postscript: meeting a Brigader

Back in 1972 or 1973 I went down to Cardiff to see an author who was writing a book for George Allen & Unwin on the National Giro. It was, I suspect, an extraordinarily dull book. By an academic who might have been called the Robert Maxwell Professor of Creative Accounting. But while I was there I went to call on a former International Brigader. He was living by himself in somewhat reduced circumstances, and had kept a cup of tea warm for me in a jam-jar next to the coal fire. He had been long-term unemployed in the 1930s, and through his union [I think] had signed up for the International Brigades. Now some forty years later he was writing his recollections of the war, writing in pencil in an old exercise book. What sticks in my mind is that he had been shot in the balls, and then invalided out with only one testicle. What he was writing was sadly unpublishable. [Though with a dedicated helper/editor, and with access to a picture library, it might have been possible to salvage something. But I was not that person.] I made some excuses, took him to the pub to buy him a couple of pints and a steak and kidney pie; and I dropped him off at the local psycho-geriatric hospital so that he could visit his wife. Who was a long-term resident there. We had no subsequent contact. I still feel guilty about the encounter.

October 2025