Anniversary

Last month, May 17th, was the 70th anniversary of the Dambusters, the celebrated raid on the German dams in May 1943. To mark the occasions hundreds of people gathered to watch a Lancaster bomber fly over Derwent reservoir, in Derbyshire’s Hope valley, one of the sites used by 617 squadron to practise for this top secret mission. Later in the day there was a second fly-past and a sunset ceremony at RAF Scampton in Lincolnshire, the station from which the nineteen Lancasters took off on their daring mission. Only three of the original squadron personnel are still alive. Les Munro, aged 94, and George ‘Johnny’ Johnson, aged 91, both attended the ceremony. Squadron Leader Munro had travelled from his home in New Zealand to be there.

The Dambusters

The Dams Raid of May 1943 was a celebrated operation. It was a positive demonstration of progress that Bomber Command had made since the beginning of the war. It was carried out by 617 squadron, which had been formed specially for this raid in March under the leadership of Wing Commander Guy Gibson, one of the leading figures in Bomber Command. The main targets were the Möhne, Eder and Sorpe dams, which were the main sources of water for the Ruhr valley, twenty miles away. And thought to be of crucial importance to German industry. The dams were attacked with bouncing bombs, which had been designed by Barnes Wallis, the scientist who had invented the geodetic technique used in the Wellington bomber. In order to be effective the bombs had to be released at the precise height of sixty feet above the ground. This was dangerously low level flying, at night, over water, for a heavy bomber.

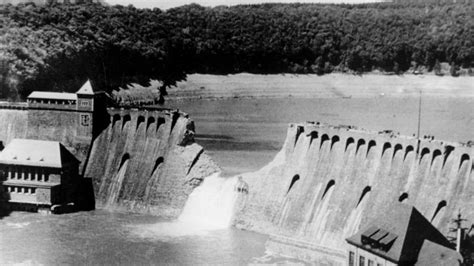

Two of the dams were breached. The destruction of the Mohne dam caused widespread flooding and disruption of railways, roads, and canals; and significantly reduced the electricity supply to the Ruhr. The destruction of the Eder dam caused considerable damage to houses, bridges, and waterways in the Kassel area. But eight of the nineteen aircraft that had been dispatched were lost and fifty-three crew members were killed.

Like many schoolboys in the 1950s I knew all this stuff. The first ‘grown-up’ book I ever read was Guy Gibson’s Enemy Coast Ahead. The book, which was published posthumously in 1946, is a remarkable account of Gibson’s life in Bomber Command; of aircrew living dangerously, and dying, as they sought our their targets in the dark skies over Nazi Germany. Gibson was a great survivor; decorated with a DFC and Bar and a DSO and Bar, he won the Victoria Cross for his leadership of the Dams Raid. Arthur ‘Bomber’ Harris wrote in the introduction “If there ever is a Valhalla, Guy Gibson and his band of pilots will be found there at all the parties, seated far above the salt.”

The myth was given further traction by the making of the 1955 epic war film The Dam Busters, based on the books by Gibson and by Paul Brickhill. The film was warmly received and became the most popular motion picture at British cinemas in 1955. In 1999 the film was voted the 68th greatest British film of the 20th century. [The film supposedly provided the inspiration for the Death Star trench run in Star Wars.] It starred Richard Todd as Guy Gibson and Michael Redgrave as Barnes Wallis. [Richard Todd incidentally entered Sandhurst in 1939, was commissioned in the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, and later joined the 7th Parachute Battalion with whom he dropped into Normandy on D-Day. He was involved in capturing the Pegasus Bridge.] Barnes Wallis, a gentle scientist, was very upset by the loss of life on the Dams Raid, and used the money he was awarded after the war to create an RAF Foundation at Christ’s Hospital. I saw a lot of him at CH in the 1950s, when he was a school governor; and when he was present at lunch parade, the band often played Eric Coates’ Dambusters March.

Operation Chastise

Now that the public library in Fountainhall Road has reopened [it was a COVID testing centre for two years], I took the opportunity to read Max Hasting’s 2019 book Chastise: The Dambusters Story 1943. Hastings is a prolific British journalist and military historian, who has edited both the Daily Telegraph and the Evening Standard. [His father MacDonald Hastings was a regular writer for the Eagle comic, also part of my reading in the 1950s.] He is the author of some thirty books, mainly on military history which get longer as he gets older. I found Chastise mercifully short, and for me it is his best book since Bomber Command written some thirty years ago.

Chastise is a more complicated story than the Paul Brickhill myth. Hastings looks at the chosen targets, suggesting that the Sorpe Dam should have been a priority rather than the Eder. But acknowledging that it was a differently constructed dam which required a different approach. He contrasts Harris’s scepticism about Wallis’s bouncing bomb and about the whole project with his willingness to soak up the credit for it when the raid became a well-publicised [partial] success. He notes that just over half of those killed in the floods were prisoners of war and forced labourers, French, Belgian, Dutch, and Ukrainian. And he poses the question: Why was there no attempt to follow up the raid. No similar high-precision, low-level raids were attempted. [Harris was fiercely crucial of ‘panacea merchants’; preferring to rely on the crude, sledge-hammer approach of ‘area bombing’. About which serious ethical questions remain.] And no attempt was ever made to bomb the reconstruction work on the dams which began immediately. The Germans certainly rose to the challenge: the dams, which had taken five years to build, were repaired by armies of forced labourers working around the clock in just five months.

Guy Gibson

Hastings also explores the story of Gibson himself. Here he leans [I think] on the 1995 biography by Richard Morris: Guy Gibson: the story of one of Britain’s most celebrated wartime pilots. A book of which I recently tracked down a copy.

Morris offers us a more nuanced picture of the man behind the legend. He notes that Gibson showed little sign of early promise. Although Sir Ralph Cochrane later wrote that Gibson was ‘the kind of boy who would have been head prefect in any school’ , Morris explains that he had a pretty undistinguished time at St Edward’s in Oxford. “He was second XV material and a lance-corporal in the OTC, moderately able, tenacious, but never getting to the top of anything.” After school he applied for a short-term commission in the RAF, and was at first turned down. Possibly because his legs were too short ! Subsequently he learned to fly at Netheravon Flying School, was neither a natural nor an outstanding pilot, but in 1937, aged 19, was commissioned as a Pilot Officer and posted to 83 [Bomber Squadron] at Turnhouse, outside Edinburgh.

When war broke out Gibson took part in the abortive attack on German warships at Wilhelmshaven. Nine Hampdens from 83 squadron took off in bad weather, failed to find the target, and returned in the dark. Their experience of night flying was negligible, but miraculously all survived. During the following years Gibson survived an enormous number of operations, initially flying Hampdens, and then Beaufighters during an unhappy eighteen months in Fighter Command. When Sir Arthur Harris took over as C-inC of Bomber Command in February 1942, he immediately recalled Gibson to command 106 squadron. Flying Avro Manchesters, and then Lancasters.

It was Harris who summoned Gibson a year later to head up the newly created 617 squadron and to lead the Dams Raid. Gibson was a veteran, a survivor, and a known name in Bomber Command. In January 1943, on a sortie to Berlin, Gibson had taken a young radio-journalist, Richard Dimbleby, with him as a passenger. The subsequent broadcast was a triumph. But Gibson seems to have had few close friends. His parents had split up. His mother turned to alcohol and died tragically in an accident shortly before the raid. He had contracted a loveless marriage to Eve, a dancer a few years older than himself. Morris interviews his ‘lost love’ in the WAAF, with whom Gibson had an unconsummated, unscheduled, Brief Encounter type relationship. His main companion and source of emotional support seems to have been his dog, a black labrador called Nigger. [I can’t remember if they changed the name in the film. They would now.]

After the raid, Gibson became a celebrity and ‘a professional hero’. He was feted by Harris and adopted by Churchill, who took him on a propaganda tour of North America, ‘all alcohol and endless adulation’. As one of Churchill’s ‘young men’, and with the enthusiastic support of William Garfield Weston, Gibson was adopted as Conservative party candidate for Macclesfield. But Gibson pined for operational flying, and once the book that became Enemy Coast Ahead was completed the RAF didn’t know what to do with him.

In June 1944 Gibson became Base Air Officer at Coningsby in Lincolnshire. Both the squadrons he had commanded, 106 and 617, where part of this group. His arrival there was a bit ostentatious and he was not universally welcomed. On his first visit to the 627 squadron mess, he was ritually debagged before being invited back for a beer. Gibson fretted that the war would be over before he could resume flying. On September 19/20th, 1944, Gibson flew as Controller and Master Bomber on a raid to Mönchengladbach and Rheydt. It is not clear who authorised this. He was flying an unfamiliar Mosquito with Squadron-Leader James Warwick as his navigator. They were both killed when the aircraft flew into a hill in southern Holland on the return leg. [As a child I found this bald statement unconvincing.] Morris investigates the reports in great detail. But it is still not clear exactly what happened. Gibson was twenty six years old.

Different people saw Gibson differently. He made little attempt to build relationships with non-commissioned men who served under him. He was unpopular with other ranks who saw him as a martinet. [The same accusation is made against Douglas Bader.] And he wasn’t that popular with his fellow pilots. One called him “a bumptious bastard”. But to one of his patrons he was “the charming boy, just like [I wish] my own son”. As Noble Frankland writes, he was an inspiration to thousands of men who served in Bomber Command. His unparalleled record of ops made him a legend in his own lifetime. Many airmen didn’t want to believe that he was dead. Richard Morris’s book is a careful nuanced portrait of the man. He doesn’t seem any less brave or admirable. But he emerges from the book as more complicated, more human – and a more interesting man.

June 2023

I loved all the D

LikeLike

Thanks, Madge. See you on Tuesday ? If the trains are running.

LikeLike

I will not be there

LikeLike