Prelude

For reasons that I can’t explain the Vietnam War largely passed me by in real time. Which is very odd. Since it was [by some parameters] the biggest war of my lifetime; and lasted under various names for about three decades. As a crude generalisation it began as a colonial war as France, the colonial power, tried to reassert control of its Indochina empire, from which it had been largely evicted by the Japanese doing the Second World War. And after the defeat of France in 1954 and the division of the country, it became a long struggle between [Communist] North Vietnam under the iconic leader Ho Chi Minh, supported by Russia and by China, and [the Democratic Republic of] South Vietnam, hugely propped up by the United States with some marginal support from other allies, Australia, New Zealand, and South Korea. It is therefore largely regarded as a Cold-War era proxy war. The war spilled over into neighbouring Cambodia and Laos. And ended with the fall of Saigon in April 1975. After which all these countries became communist states.

I am making up for my earlier lack of attention by reading some books about Vietnam. Some of which are extremely good.

Dien Bien Phu

After the fall of Japan in 1945 Ho Chi Minh declared the establishment of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.. A month later French forces overthrew the DRV and restored French authority in Cochinchina. What began as a low level insurgency against the colonial power turned into a conventional war fought between the Viet Minh, supplied by the Soviet Union, and French forces, largely comprising French colonial troops drawn from North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, and from Indo-China, supplemented by units of the Foreign Legion. The Viet Minh relied mainly on guerrilla tactics and ambushes, while the French tried unsuccessfully at first to draw the enemy into a major confrontation. Culminating in a decisive [and disastrous] defeat for the French at Dien Bien Phu.

When we were last in Grenoble I found a copy of Martin Windrow’s book The Last Valley in a charity shop. Price 2,00€. It was a good buy. Martin Windrow is a journalist and publisher rather than an academic historian. He has written a magisterial account of Dien Bien Phu, the battle that doomed the French empire and which lured America into Vietnam. In the winter of 1953-54 the French army under the command of General Henri Navarre challenged General Giap’s Viet Mnh to a pitched battle. [Navarre was intellectually brilliant, with background in intelligence work and an air of calm authority. But he had no experience ofAsian warfare, and was referred to by a colleague as “an air-conditioned general”.] Thousands of French and Vietnamese paras and légionnaires, with supporting artillery and tanks, were flown to the remote valley of Dien Bien Phu in north-west Vietnam to build a fortress upon which Giap could smash his inexperienced regiments. But fortress is a misleading term; it was no more than a chain of low hills set in a shallow valley surrounded by densely wooded mountains.

The siege began in December. And lasted for three months. As Martin Windrow tells the story it assumes the character of a Greek tragedy. The French were amazed to learn that the Viet Minh besiegers had dragged heavy artillery over five hundred miles of roadless, jungle terrain. And working from bomb-proof caves and excavated tunnels, they could shell the French troops with impunity. General Giap described the siege as grignotage, a constant nibbling away. The French commander at Dien Bien Phu was Colonel Christian de Carries, a dashing cavalryman, aged 51, tall with silver-grey hair, obliged to walk with a shooting stick as a reminder of old wounds. de Carries lacked any gift for inspirational leadership. Which came mainly from his subordinate, Lieut.-Col. Pierre Langlais, a tough 44-year-old paratrooper with a taste for whisky and a sulphurous temper, who had previously served with the Saharan camel companies of the African Army, in Italy, and Alsace and Germany, and was now on his third tour in Indochina.

The outer forts of Béatrice and Gabrielle were overrun by the Viet Minh in mid-March. Colonel Charles Piroth, de Castries’ popular artillery commander, was severely criticised by Langlais; retreated to his tent and killed himself with a grenade. Garrison morale was now crumbling. Astonishingly [to me] several hundred untrained parachutists dropped into Dien Bien Phu in April. As de Castries observed in a subsequent report, “It’s a bit like Verdun, but Verdun without the depth of defence … … and, above all, without la Voie Sacrée … ”. A relief column of three thousand men set out from Laos, but it was a hopeless venture. On May 7th de Castries formally surrendered to the Viet Minh. Who suddenly found themselves with five thousand prisoners, most of them wounded. More of de Castries’ men died in captivity than died in action. France had lost the will to pursue the struggle. The new French prime minister, Pierre Mendès-France, promised a cease-fire within thirty days. In July at the Geneva Conference it was agreed to partition the country close to the 17th Parallel. The Cease-Fire was signed by France and by North Vietnam. The agreement was endorsed by the French, the British, the Chinese, and the Russians. Ho Chi Minh accepted that hegemony over a united Vietnam would have to wait for another day. No Westerner saw the Geneva agreement as a success. It was rather an exercise in damage limitation.

The Best and the Brightest

How then did America then get involved ? That question is best answered by David Halberstam’s book The Best and the Brightest. Halberstam was a journalist for the New York Times, who wrote extensively on politics, history, the Civil Rights movement, American culture, the Korean War, and Vietnam. He arrived in Vietnam in 1962 and left again in 1964 aged thirty. He arrived as a confident man, a believer, welcomed by the American Embassy in Saigon. But his two years in Vietnam, during which time he witnessed the self-immolation of the Buddhist monk, Thich Quang Durc, made him increasingly critical of [the South Vietnam] President Diem’s government, and also of the upbeat and misleading utterances of General Paul Harkins and the American military.

I found a copy of The Best and the Brightest, first published in 1969, in Shakespeare’s quirky bookshop in Paris in the mid-1970s. but the copy on my shelves is the twentieth anniversary edition. The genesis of the book, Halberstam says, was a return trip he made to Vietnam in 1967, when he was struck by the stalemate – American military superiority against North Vietnam’s political superiority. And by the self-deception of senior Americans in Saigon that we were on the edge of a final victory. Eventually the Americans would have to go home and so Hanoi controlled the pace of the war. The American generals, like the French generals before them, were not so much in the wrong war as on the wrong planet. His views went down badly with American ambassador, Ellsworth Bunker. Who believed that overwhelming American fire-power made victory inevitable.

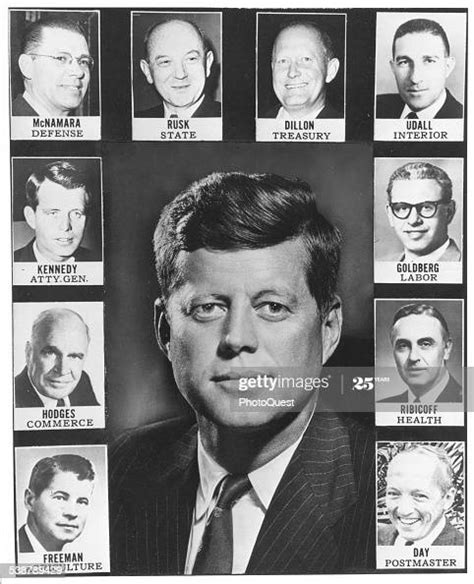

Back in the States Halberstam started work on a book about “how and why we had gone to war in Vietnam, and about the men who were the architects of the war”. His writing began with an article for Harper’s on the iconic figure of McGeorge Bundy; the most luminescent of the Kennedy people, Dean of Harvard at a ridiculously young age, the most cerebral member of the Kennedy Administration, and the likely leader of the next generation of the American Establishment. The article, The Very Expensive Education of McGeorge Bundy, provoked a stormy response. It was the first time that a [liberal] journalist had suggested that the decision making of the Kennedy Administration on Vietnam was significantly flawed. How could so many brilliant people have made such bad decisions ? Perhaps because the members of the Administration were given credit for cerebral prowess and academic success rather than accomplishment in government. Halberstam tells a wonderful story about Vice President Lyndon Johnson:

“After attending us first Cabinet meeting he went back to his mentor Sam Rayburn and told him with great enthusiasm how extraordinary they were, each brighter than the last, and the smartest of them all was that fellow with the Staycomb on his hair from the Ford Motor Company, McNamara. “Well, Lyndon, Mister Sam replied, “you may be right and they may be every bit as intelligent as you say, but I’d feel a whole lot better about them if just one of them had run for sheriff once”. “

Back in 1954 the young Democratic senator had opposed intervention in Indochina; “to pour money, men, and materials into the jungles of Indochina would be most unlikely to deliver victory against a guerrilla enemy … which has the sympathy and covert support of the people”. But now, as advised by his favourite general Maxwell Taylor, Kennedy tried to solve the Vietnam problems by sending a steady flow of Americans, Green Berets, military advisors, helicopters and helicopter pilots. By November 1963 there were sixteen thousand Americans on the ground. In the years that followed Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, an enthusiast for slide-rules and systems analysis, egged on by the RAND Corporation, presided over a steady, inexorable increase in numbers. But the Kennedy-Johnson administrations never defined the war, what America’s role or mission was, how many troops would be sent, and, most important of all, what America would do if the North Vietnamese matched American escalation.

Halberstam offers a fascinating set of pen pictures of the major players, both military and civil. He emphasises the enduring legacy of the McCarthy era, though Joe McCarthy himself had died seven years before Kennedy took office. The Republican party, long out of power, [until Eisenhower “a kind of hired Republican” was elected] accused the Democrats of treason; there were sustained attacks on Truman and Dewey for their policies in Asia which had “lost China”. The fear of being soft on Communism lingered among Democratic leaders. The memory of the fall of China was even more bitter for Lyndon Johnson than for John Kennedy. Johnson vowed that he would not be the president who lost the Great Society because he lost Saigon.

The book doesn’t go beyond the 1968 election. The tormented McNamara has gone, no longer a believer. Johnson stands down as President, destroyed by a war he didn’t want. [Hey, hey, LBJ/How many kids you killed today ?”] Hubert Humphrey becomes the Democratic nominee, but in so doing loses what is left of his reputation. Ironically it is the newly elected President, Richard Nixon, who goes to China and through Henry Kissinger embarks on the lengthy [and thoroughly cynical] process of American withdrawal. “The only political figure who could go to China,” Halberstam notes, “without being Red-baited by Richard Nixon”.

Max Hastings: Vietnam

All this and a great deal more is in Max Hastings book, published in 2018, which I began to read in Normandy and have now finished. It is a long [700-plus pages], a balanced, magisterial account of the war[s] in Vietnam. Anthony Beevor calls it “his masterpiece”. Unlike Halberstam, Hastings is primarily concerned with Vietnam rather than with the United States.

The book starts with the post WWII colonial war against the French culminating in Dien Bien Phu and the partition of the country. And continues with a political and military narrative; from Kennedy sending 400 Green Berets in 1961 through the massive expansion of US military and materiel under Johnson and McNamara. Through to the collapse of Saigon in May1975. After which, in Michael Howard’s words, “a grey, totalitarian pall descended on the country”.

After the Tet offensive of 1968, which provoked Johnson to withdraw from the election race, his spirit broken by Vietnam, Hastings reckons that North Vietnam’s defeat was no longer plausible. But the war had a further seven years to run. With the South ‘losing by instalments’.

Hastings is good on the ‘on the ground’ experience, ‘Waste deep in the Big Muddy’. He criticises equally incompetence and corruption in both the North and the South. He believes that America’s military power could never match the North’s political power. As the journalist Neil Sheehan observes, “In the south there was never anything to join up to …”.

The war cost the States $150 billion [less than Iraq two decades later]; and 58,000 lives [proportionally fewer than the Korean War]. But the true price was the trauma that it inflicted on the country. The war was a catastrophe for Vietnam. And, as General Walt Boomer comments, if the States had learned anything from the Vietnam War, they wouldn’t have invaded Iraq.

PS

We should give Harold Wilson belated credit for resolutely keeping British troops out of Vietnam, in spite of American blandishments. Sadly Tony Blair, seduced by the glamour of George W. Bush [difficult to believe, I know] failed to follow his example a generation later on Iraq.

August 2023

Thank you for this post. I was too young to be sucked into the Vietnam War, but my father, a 20-year Army officer did two tours. He served well out of harms way, if you ignore the generalized dousing with defoliants, and the Tet incursions. As a senior officer in Graves Registration (mortuary services) he saw firsthand the carnage inflicted on U.S. troops and civilians alike. Mostly because the bodies were usually such a mess that it was only after careful forensic work that it could be determined whether it was a U.S. soldier, a Vietnamese soldier or insurgent, or a civilian. My uncle described him as being a shattered shell of himself when he returned from his second tour.

I was inspired to finally read ‘The Best and the Brightest’ based on your post. It had been lingering on my to-be-read list for years. I had read Robert Schulzinger’s ‘A Time for War’ for a clear depiction of the Charybdis the U.S. found itself in. If I can find the bandwidth, I will try the Max Hastings book. Halberstram’s book does a good job fleshing out all the political machinations and hallucinations by the intellectual conclave that rowed the U.S. ever closer to the vortex.

Karl Marlantes, an ex-marine and (yet another!) Rhodes scholar, wrote a fictional, but compelling story of the dysfunctional military failures that Vietnam troops on the ground were subjected to in ‘Matterhorn’ that bookends nicely with the non-fiction books. Not quite a ‘Catch-22’, but a compelling, strong indictment of the air-conditioned majors, colonels and generals that were charged with managing the actual fighting. About the only people to come out of the Vietnam War without being figuratively covered in mud were the grunts in the mud.

LikeLike

Steve

Many thanks for this. I’m sorry about the tardy response; we have been away on a short trip up to the Hebrides. I was sorry to hear about the effect the Vietnam War had on your Dad. I guess we failed for a long time to fully understand the mental toll of wartime experience and memories. The First World War comes immediately to mind. It is heart-wrenching to think of all those combatants who suffered various forms of shell-shock, and who were then shot as deserters. I hope you enjoy the Max Hastings book. I have a book here, Derailed in Uncle Ho’s Victory Garden, by Tim Page, a Vietnam War journalist who went back to the country some 30 years later. It got very favourable reviews, but I haven’t yet got round to reading it.

LikeLike