Tony Judt

We were in Callander in June on the way north towards Arisaig and Skye. Normally it is just a coffee stop. But this year we bought some [very] expensive shoes in the Rogersons factory shop. And I was pleased to find a clean hardback copy of Tony Judt’s The Memory Chalet in the Cancer Research Shop for £2.00.

I first came across Tony Judt on the bookshelves of Liz’s house in Etterbeek, in Brussels in 2013. I had no idea who he was. But Liz had a copy of Ill Fares the Land, his 2013 book, which I read with enthusiasm. It is a lament for the breakdown of the [British] postwar consensus on economic policy [Butskellism], and a slaughtering attack on the rise of neoliberal economics as it emerged under Thatcher and Reagan. Judt deplores the rise of unregulated capitalism that precipitated the 2008 global financial crisis. And he makes a powerful case for the restoration of social democracy and the notion of a social contract to further equality of opportunity and the common good.

Outside Liz’s house in Brussels, 2013

Judt it subsequently transpired was in essence an academic historian. He came from a secular Jewish family in south London, was educated at Emmanuel School, Wandsworth [as was my brother Paul], and subsequently at Cambridge and at the Ecole Normal Supérieure in Paris. After completing his Cambridge doctorate, his academic career was divided between Cambridge, the University of California at Berkeley, Oxford [St Anne’s College], and New York.

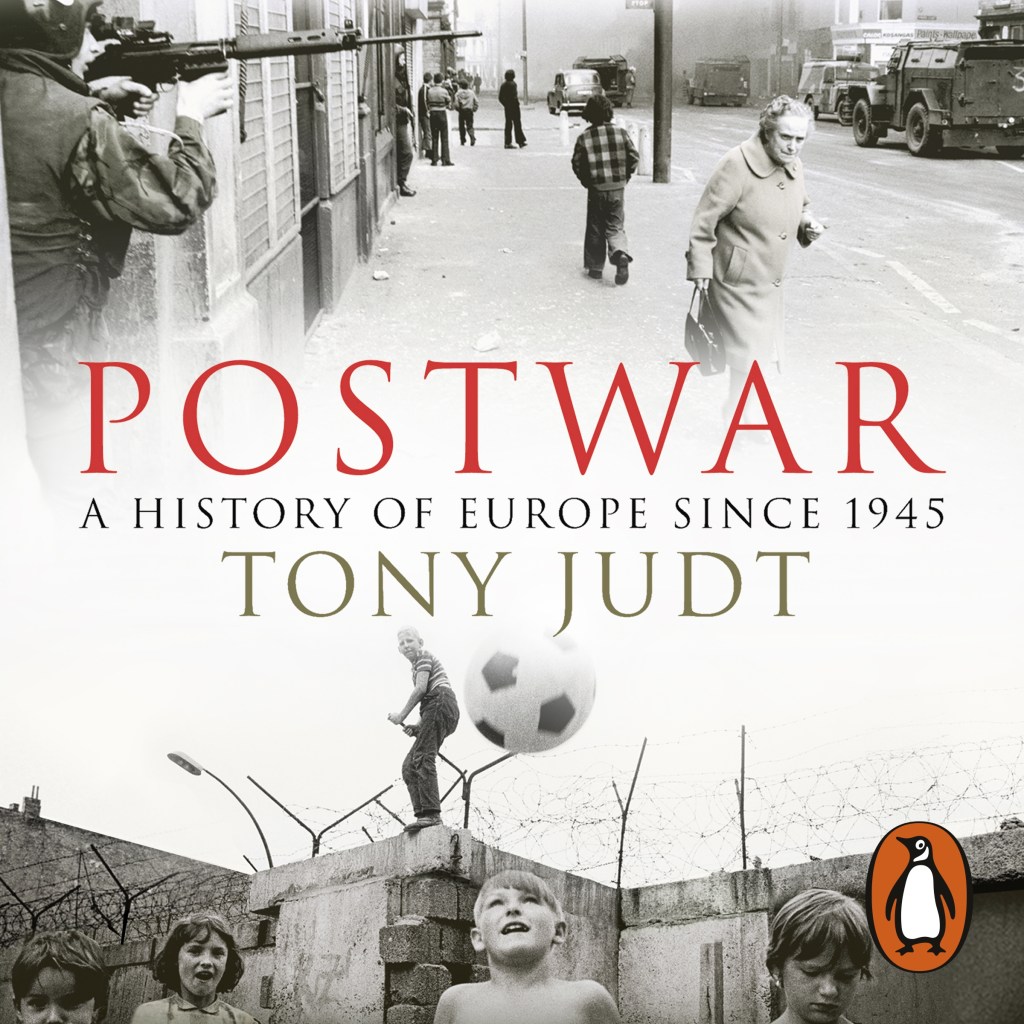

Postwar

Judt’s best known book is his Postwar [published 2005], a magisterial history of Europe after the Second World War, which I first saw on the bookshelves of Guy Milton in Brussels. It is an exhaustive, and exhausting, book, which I read in Strasbourg during the summer months of 2016 while doing a locum spell there. Where he had previously been thought of as a specialist in French social and intellectual history, Judt now spreads himself across a wider canvas. The book starts by surveying the state of Europe in 1945: everyone and everything, with the notable exception of the well-fed Allied occupation forces, was worn out, without resources, and exhausted. It is estimated that some 36 million Europeans died between 1939 and 1945 from war related causes; more than half of them non-combatant civilians. Post-war Europe, especially in central and eastern Europe, suffered from an acute shortage of men. In Germany itself two out of three men born in 1918 did not survive the war. Surviving the war was one thing, surviving the peace was another. “Better enjoy the war”, was the rueful wartime German joke, “the peace will be terrible.”

Involuntary economic migration was the primary experience of World War Two for many European civilians. Few Jews remained; of those who were liberated from the camps, four out of ten died within a few weeks of the arrival of the Allied armies. Whereas at the end of the First World War borders were adjusted and invented, after 1945 the opposite happened; boundaries remained broadly intact and people were moved instead. Post-war Europe was essentially a Europe of homogenous nation states.

From this scene of a devastated Europe in 1945, Judt traces a broad pattern: 1945-53, the years of rehabilitation and the coming of the Cold War; 1953-71, the politics of stability and the age of growing affluence; 1971-89, a time of diminished expectations, the end of the post-war economic boom, the steep rise in oil prices, the accelerating rise of job losses in all traditional industries, the emergence of violent protest groups – ETA and Basque terrorism in Spain, the Baader-Meinhoff gang and the Red Army Fraction [the RAF] in Germany, the Red Brigades in Italy, the Provisional IRA in Ireland. Followed by major upheavals in Eastern Europe culminating in the collapse of the Soviet Empire and the dismantling of the Berlin Wall.

Writing in 2005, Judt was broadly enthusiastic about the European Community. But he pointed to some of the inequalities of EU policy and envisaged an important role for the nation states in the redistribution of wealth and the preservation of the decaying social fabric. Postwar was runner-up for the 2006 Pulitzer Prize for non-fiction, and in 2009 was acclaimed by the Toronto Star as the best historical book of the decade..

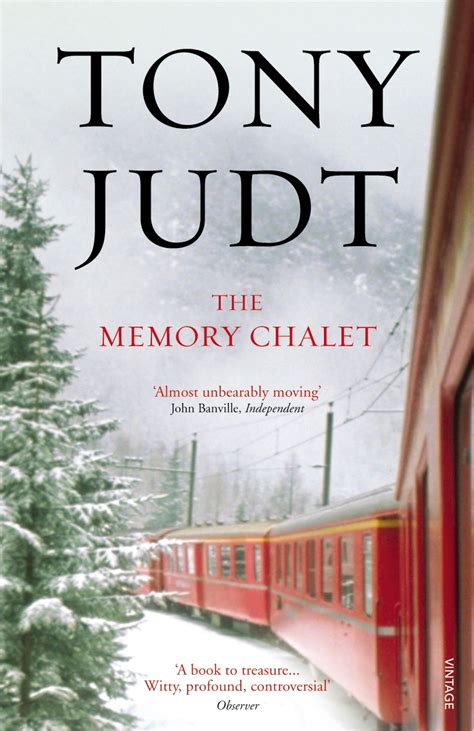

The Memory Chalet

As the early chapters explain, Judt was diagnosed in 2008 with ALS, a kind of motor neurone disease, a crippling neurodegenerative disorder. He is writing the book in May 2010 effectively a quadriplegic, unable to move his arms or his legs, lying in bed trussed up, myopic, and motionless. He is unable even to scratch himself. But his brain is clear to reflect upon the past, and the memory chalet of the title is a mnemonic device which enables him to sort and to store his personal memories, and to set these in a wider historical context.

Judt grew up in a secular Jewish family in south London in the age of post-war austerity. People dressed in modest colours – brown, and beige and grey, and led remarkably similar lives. As a child he was brought up on English food; not fish and chips, and toad in the hole, and spotted dick, but brown bread and brown rice and green beans, the healthy staples of an Edwardian left-wing diet. “My mother could no more cook brown rice than she could cook chop suey. And so she did what every other cook in England did in these days – she boiled everything to death”. By contrast the food at his paternal grand-parents in North London was Northeastern European Jewish; brown potatoes, brown swedes, and brown turnips; cucumbers, onions, and other harmless, small vegetables came crunchy and pickled; fish – gefilte, boiled, pickled, fried, or smoked – was omnipresent, and seemed always to smell of spiced and preserved sea creatures.

Judt’s father, born in Belgium and raised in Ireland, was obsessed with motor cars. And in particular with idiosyncratic Citroëns. They were technologically advanced but not very reliable. “Just as my father resented Nescafé and preferred Camembert, so he disdained Morrises, Austins, Standard Vanguards, and other generic English products, looking instinctively to the Continent”. Judt dutifully accompanied his father to motor sport rallies in Norfolk or the East Midlands; grown men discussing carburettors for hours at a time. Better were long summer continental road trips in the days before autoroutes. Tolerated with difficulty by Judt’s mother. “Considering the amount of time we spent on the road in those years, it is remarkable that their marriage lasted as long as it did”. His father’s love affair with the company culminated in him becoming President of the Citroën Car Club of Great Britain.

The family lived from 1952 to 1958 in Putney, in south west London. They lived in an apartment in a Mews near the river, in which two of the six stables were still occupied by working horses. Other stables were occupied by electricians, mechanics, and general handymen; like the milkman, the butcher, and the rag-and-bone man all were locals, the children of locals. There were chain stores along Putney High Street, but even these were somehow local. Sainsbury’s, a small shop with just one double-window, still had sawdust on the floor. Putney was still a village. [I grew up at the same time in Southfields, a tube stop away on the District Line. Putney High Street was the first place where I experienced the aroma of roasting coffee, in a shop next door to Putney Station.]

Judt writes nostalgically about Green Line buses, green and single decker in contrast to other London buses, which took largely middle-class commuters across large tracts of Green Belt countryside. He enthuses too about the pre-privatisation rail network, while regretting their early switch to diesel instead of electric. ‘The Continent’ was still an alien place in the 1950s, but the Judt family crossed the channel relatively often, including using the SNCF pre-war steam the SS Dinard, onto which cars were still individually loaded by crane. Ironically he notes that continental travel is still associated with English breakfast; eggs, bacon, sausages, tomato, and beans, accompanied with white-bread toast, sticky jams, and British Railways’ cocoa. For Judt the indigestible English breakfast continues to evoke memories of France in the manner of a Proustian madeleine.

He hated school, a Victorian establishment with cream and green corridors, nestling between two railway lines coming out of Clapham Junction. In 1959 many of the masters had been there since the end of the First World War, and small boys were regularly beaten for insubordination. Judt is particularly unenthusiastic about the CCF [Combined Cadet Force], in which small boys were instructed in basic military drill and the use of the Lee Enfield rifle – already obsolete when it was issued to British soldiers in 1916. The only master he admires is Joe Craddock, apparently a gaunt misanthropic survivor of some past war, but an impassioned and enthusiastic teacher of German.

“My Sixties were a little different from those of my contemporaries. Of course I joined in the enthusiasm for the Beatles, mild drugs, political dissent, and sex [the latter imagined rather than practised’ … The big difference was that Judt was committed for most of the 1960s to left-wing Zionism, and spent the summers of 1963, 1965, and 1967 working on Israeli kibbutzim. Which involved a great deal of hard work, as the Jews came back to the land after their rootless diasporic degeneracy. Muscular Judaism was healthy and purposeful and productive. But Judt came to resent the smug self-regard of the kibbutz dwellers. Who were appalled when he left them to go up to Cambridge, which they saw as an act of individualism and of betrayal.

Judt arrived in Cambridge in 1966, a time of rapidly shifting cultural mores. He reflects on the curious relationship between male students and the ‘bedders’, ladies of a certain age who acted as servants. Studying subsequently in Paris, at the ENS, is more intellectually exciting, though he notes the relative immaturity of his fellow students, all of whom had been force fed for the entrance exams. He notes that English students were preoccupied with sex, but did surprisingly little; while French students were more sexually active, but kept sex and politics quite separate.

Go West, Young Judt

In 1975 Judt makes his first visit to the States. He and his English wife drive across the country to Davis, California. He is struck by the size of American pizzas, and of everything else; and by the American obsession with cleanliness. And by the resources of the universities; at Bloomington the University of Indiana has a 7.8 million volume collection in more than nine hundred languages.

In the 1980s Judt, now teaching in Oxford has a mid-life crisis; he divorces wife number 2, starts to learn Czech, and then to study and to teach East European history. He meets the new generation of leaders and re-connects with his own East European Jewish past. He develops the distinctive Czech qualities of doubt, cultural insecurity, and self-mockery. By 1992 Judt is chairman of the History department at New York University “where I was the only unmarried straight man under sixty”. It is in the rich cultural mix of New York that he evidently feels most at home. He even marries one of his students, a former professional ballerina with an interest in Eastern Europe.

Judt died in August, 2010 at the age of 62, and the book was published posthumously. I loved the book. Judt’s precise memories trigger reflections on wider issues; urban planning, student riots, sexual politics, American history. There is an unspoken contrast between the restlessness of his mind and the static imprisonment of his body. His conclusion is that his generation was “a revolutionary generation which missed the revolution”.

Envoi

In Edinburgh the Festival and the Fringe are over. Our little flurry of visitors has come to an end. My friend Pete didn’t make it up from Gloucestershire; short of energy or short of funds ? We have sunshine and showers and a lot of wind. It starts to feel distinctively autumnal. Susie and I are going down to Wycombe next month to be with the girls while Craig is away walking the Ridgeway. Can we take walking poles on the flight down ? Meanwhile Susie is busy gardening. And I am rather ineffectually sorting through a pile of unwanted books.

August 2024

Ah, not often that you see a picture of Emanuel (sic) School on Facebook or anywhere else. And in the sunshine. Memories from way back, the 1950s, are less bright, more grey. Emanuel was indeed a somewhat drab place, mostly lacking in scholarship but making up for it through playing at soldiers and derring do on sports pitches or the water. Despite that, some survived and did rather well. Judt, I recall, detected touches of antisemitism at Emanuel. Somehow I doubt whether the vast majority of pupils knew what the word meant, let alone be able to recognise it. As for Craddock, he was undoubtedly a linguist of rare skills, a desk loitered with dictionaries but never, seemingly, into English. You could hear his screams a stairwell away and resigned yourself to lessons of barely controlled violence. There were better than him on the staff. I have the feeling that Emanuel is now so very much better.

LikeLike