The good news is that the magnolia is about to come out in the front garden. I’m reluctant to write about Donald Trump. Seeing him on the television news fills me with revulsion. [I feel the same way about Benjamin Netanyahu.] Back in October 2020, when I had started writing this blog, I addressed the question, ‘Why do so many American Christians vote for Trump ?’ Catholics as well as Evangelicals apparently. I described Trump as “a greedy, boastful narcissist with a limited understanding of the world and a greatly inflated idea of his own abilities. … … who presents himself as a Christian, as a Presbyterian, and as a Pro-Life candidate, which plays well with his supporters.” And I was promptly assailed by an American reader, whom I don’t know, who told me very clearly that, whatever Trump’s deficiencies, Joe Biden had definitely lost his marbles. Sadly, she may have been right.

Learning lessons from history is sometimes a dangerous way to proceed. But in view of the ongoing and very difficult problems in Ukraine. I was interested to pick a book off the shelves which I don’t ever remember reading. A book that tells the complicated story of American foreign policy in the 1990s, specifically in the days when Bill Clinton succeeded George Bush senior as president..

David Halberstam: War in a time of Peace: Bush, Clinton, and the Generals

Halberstam is an American journalist, who wrote The Best and the Brightest, a long and complex [and, I think, brilliant] book about how the States became embroiled in the Vietnam War. The book won a Pulitzer Prize. In this more recent book [published in 2001] he tells the story of the making of American foreign policy in the post Cold War era. As in his earlier work, he explores in some details the internecine conflicts and the struggles for dominance among the key players in the White House, in the State Department, and in the military. An abiding theme is the tension between the military, who were determined never again to be trapped in an inconclusive ground war; and civilian advisors and officials, most of whom had never served in the military. And who thought for a mix of reasons that America should ‘do something’. The book offers fascinating mini-biographies of the men [and they were mainly men] involved; Bush senior, Reagan, Kissinger, Clinton, Colin Powell, General John Shalikashavili, and Madeleine Albright among others.

One aspect of the story that struck me is the enduring heritage of the Vietnam war. For both civilians and military. Clinton and the Democrats were intensely aware that it was Democratic presidents who had committed [for whatever motives] to Vietnam, that is John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. Yet most of the anti-war protests had come from the left-liberal wing of the party. Making the Democrats a family seriously in conflict with itself. By the time Clinton was elected, the Democrats had been out of office for twelve years and the Clinton campaign had been very much focussed on domestic issues. On the other hand Bush had negotiated the end of the Cold War and overseen the relative success of the Gulf War, and Bush himself had been a hero as the youngest naval pilot in World War II. But he fought a terrible campaign, was handicapped by his lack of eloquence; and he and his people significantly underestimated their opponent, Bill Clinton. [Halberstam compares Bush losing in 1992 with Churchill losing the General Election in 1945 to Clement Attlee. Though I didn’t think anyone could ever confuse Attlee and Clinton !]

Bill Clinton was the first true post-World War II, post-Cold War president. The defining personal issue for him was racial change in the south. He had been a Rhodes scholar at Oxford, an experience that was designed to introduce talented young Americans to the rest of the world, especially England and Europe. But foreign policy remained distant to him. When Lee Hamilton, the veteran congressman who headed the House Foreign Affairs Committee, tried to engage with him on issues like post-Soviet Russia and relations with China, Clinton interrupted him: “Lee, I just went through a whole election campaign, and no-one talked about foreign policy at all … except for a few journalists”. Hamilton, who was a bit put out, responded: “You know every president’s tenure is marked by foreign policy issues whether they like it or not. It just happens that way. No American president can avoid it because he’s the leader of the free world. They think they can, but they can’t”.

And Hamilton’s words were prescient. Unrest in Somalia had escalated in to a full-blown civil war in 1991. Bush had sent 25,000 soldiers there as part of a UN peace-keeping force, and 4,000 were still there in late 1993. But in October 1993 a failed attempt by US special forces to capture warlord Mohammed Farrah Aidid led to the deaths of eighteen American soldiers. In addition seventy four soldiers were wounded and two helicopters lost. Questions were asked about the value of US troops in Somalia, and Clinton removed all US military from the country in early 1994. Somalia was a fiasco: it was a tragedy for the families of the young men killed, a tragedy for an uncertain administration, and a tragedy for the Somalis themselves. It was also a tragedy for anyone who believed that America had an increased role to play in humanitarian peacekeeping operations.

The geopolitical consequences of what had happened in Somalia tragedy were soon felt elsewhere, first in Haiti and then in Rwanda. In Haiti Clinton made an election pledge to confront the junta led by General Raoul Cedras, and to restore the elected president Jean-Bertrand Aristide. But many Americans were opposed to military intervention in a country which posed no risk to the United States, and Clinton stood down troops who had already embarked for Port-au-Prince.

In 1994 the Hutsis in Rwanda embarked on a genocidal killing of the minority Tutsis, killing some 800,000 people in the course of three months. There was a clear need for some kind of outside, peacekeeping intervention, but the Clinton administration wanted no part of it. There was a very limited force sent by the UN to provide aid, but the American feeling was that “we had no dog in the fight”. Clinton some years later said that the failure of the United States to intervene in Rwanda was the biggest mistake of his administration.

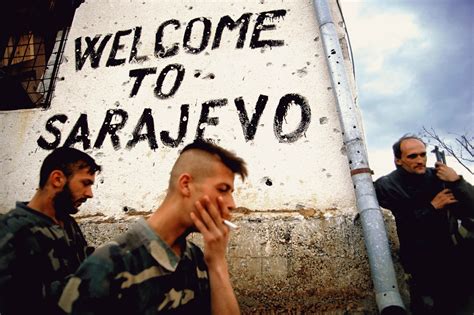

The other long-running problem of the 1990s was the fighting in the Balkans following the break-up of the former Yugoslavia. After Slovenia and Croatia, and then Bosnia-Herzegovina, had all declared their independence, the Serbs under their nationalist leader Slobodan Milosevic invaded their neighbours on behalf of fellow Serbs. Ethnic cleansing campaigns were initiated by the Bosnian Serbs, and their policy of concentration camps and the widespread killing of civilians aroused worldwide condemnation. Whether or not America should intervene in the former Yugoslavia was the great foreign affairs question of the Clinton years.

The situation deteriorated in spring 1995. The Bosnian Serbs laid siege to the three, predominantly Muslim, Bosnian towns that lay outside their control. Of the three the one that had the dubious honour of becoming the best known was Srebrenica. It came to symbolise the evil and the suffering of events in Yugoslavia, and entered the list of tragic places like Lidice and Katyn and Nanking in World War II which were the sites of state-ordered genocide. Halberstam traces the tortuous evolution of American policy in Bosnia and subsequently in Kosovo in considerable detail. As the military told the civilians that it might be ‘quite easy to go in, but a lot more difficult to get out again …’ without a lot of casualties.

1990s characters

Halberstam is wonderfully long-winded, if you like that kind of thing; reluctant to limit himself to one word where three will do. He can’t introduce a new character without offering us a mini-biography and character sketch. And the background of some of the lead characters is fascinating. Colin Powell was Chairman of the JCS under Clinton, the senior military man, an imposing and charismatic figure, popular across party lines and potentially a future presidential candidate [and rival to Clinton]. He was the son of Jamaican immigrants, and a product of the Bronx and CCNY’s ROTC programme, a very different background from many of his fellow military.

His successor, John Shalikashvili had arrived in the States as an immigrant in 1952 and had learned much of his English from John Wayne films. His father was from the Soviet republic of Georgia and his mother was a Polish national of German extraction. His father had fought with the Polish cavalry against the Germans early in World War II, but subsequently served in the Georgian Legion under the German flag, fighting in Normandy to repel the Allied invasion. And then with the Waffen SS in Italy. [This was a piece of family history that was kept carefully secret when the family later emigrated to the United States.]

Madeleine Albright, who became Clinton’s Secretary of State in 1997, and who became the leading hawk on Bosnia and Kosovo, was another who had arrived as an immigrant in the States. Her father had been a Czech government official in the years after World War II, but the family arrived in the States in 1948 to escape a Soviet coup. Both her parents were of Jewish origin, but in 1941 they had become Roman Catholics and they kept their ethnic origins a secret from their children. It was only after she became Secretary of State, and a Washington Post journalist started to investigate her background, that Albright discovered her Jewish origins. And that many of her family had perished in the Nazi death camps.

Lessons to learn ?

There is much fascinating stuff in this book. I guess the first thing that I came to appreciate is that many parts of the world seem very remote to Americans. Ukraine today is as remote from the concerns of many Americans, as were Somalia and Rwanda, Bosnia and Kosovo in the 1990s. James Baker’s verdict on the Balkans, “We don’t have a dog in that fight” echoed down the years. I think that Clinton’s idealism perhaps did make him want to step in where there was obvious injustice or genocidal acts. But the post-Cold War world was a messy place, and there were always good reasons not to intervene in situations that might turn nasty. Better to ignore them.

Secondly, I was greatly impressed by the calibre of policy makers under Clinton. Men like Warren Christopher [at State], William Perry [at Defense], Tony Lake, and Richard Holbrooke [the architect of the Dayton Agreement that ended the Bosnian War] were all educated, experienced professionals, with lengthy careers in public service. Totally unlike the bunch of Trump cronies, whose main talents seem to be money making and tax evasion. Halberstam notes approvingly that Clinton himself had invariably read everything, books and background papers. While Trump is seemingly proud of the fact that he has never read a book in his life.

And the American electorate has changed too. Halberstam notes that Clinton faced virulent opposition from the very start of his first administration. Part of which was driven by the new force of talk radio; it was right wing, it was populist, and it was angry.

“It represented a new kind of disenchanted American, more often than not white male and middle to lower middle class, who thought he was disenfranchised by the current culture, which flouted what the right wing called family values, and the current economy, which favoured those who had a certain kind of education over those who did not; it was often rural and small town and nativist. It was also anti-feminist, anti-gay, anti-liberal and as such vehemently anti-Clinton. Its constituents had not always been to Vietnam, although they sometimes sounded as if they had, often referring to it as Nam … people who believed that they were the forgotten men and women of America”.

This sounds to me much like the Trump supporters who invaded the White House four years ago. And who strongly resent any notion that the States should be the world’s policeman, willing to intervene in conflicts around the world on behalf of democracy and justice. And peace.

Envoi

I enjoy Halberstam’s books. But I need a break from American politics. As the magnolia stellata comes into flower, and as we journey slowly through Lent,I am going to look again at two profound books by the English theologian W.H. Vanstone.

March 2025

Dear Chris and Susie

I love magnolias we have several. One a whie stellata like yours was a 50 present to Terry from his father, and we added a pink stellata later, then when Janet married she and Phil gave us a big magnolia called Susan .

I have long realised that Americans don’t want to know about the rest of the world and it colours all their foreign policy

.love to you from France,# Madge xx

LikeLike

Thanks, Madge. Are you currently back in France ? Where I guess Spring may be a bit ahead of us here. The only drawbackwith the magnolia stellata is that it is a bit fragile; any wind or strong rain, and it loses all its petals. love from us here

LikeLike