Last year I read most of Evelyn Waugh’s earlier books, the novels that is not the travel writing which has dated badly. The conventional wisdom is that the First World War produced great poetry, think Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon, Edmund Blunden, Ivor Gurney and Isaac Rosenberg; whereas the best known writers of the Second World War produced mainly fiction, think Olivia Manning and Evelyn Waugh, and abroad Norman Mailer, Joseph Heller, Günter Grass, and Kurt Vonnegut. The Sword of Honour trilogy, based on Waugh’s own wartime experiences, are certainly Waugh’s most ambitious books. I believe that it is on this mature writing that Waugh’s reputation as a major novelist rests.

Waugh at War

With hindsight it is easy to say that Waugh was not cut out to be a soldier. His free spirit was not suited to the military life. But after the outbreak of the war in 1939 Waugh was proud to be accepted as a successful candidate into the Royal Marines. Initially he enjoyed the ceremonial trappings, the gastronomic quality of the mess, the reflection of the silver candelabra on polished mahogany tables, the ritual clockwise circulation of the port. Life in the Marines initially suggested that he might be able to be both an aesthete and a man of action. But his infatuation with life in the army lasted only a few months. In April 1940 he was temporarily promoted to Captain and given charge of a company of marines. But he was an unpopular officer, vacillating between strictness and laissez-faire with his men. His inability to adapt to regimental life meant that he lost his command, and instead became the battalion’s Intelligence Officer. In August 1940 he took part in the Dakar Operation, which was hampered by fog and poor intelligence which caused the troops to withdraw.

Operation Menace – the Dakar fiasco

In November 1940 Waugh was posted to a commando unit, Layforce, serving under Colonel Robert Laycock. In February 1941 Layforce sailed to the Mediterranean and were involved in an unsuccessful attempt to recapture Bardia. Later in 1941 Layforce were involved in the evacuation of Crete. Waugh was shocked by the general air of chaos around the withdrawal, and by what he saw as loss of leadership and of cowardice among the departing troops.

The defence of Crete

Crete was effectively the end of Waugh’s active military service. In May 1942 he was transferred out of the commando into the Royal Horse Guards, but they struggled to find a role for an insubordinate and unmilitary officer. In January 1944, after being granted three months unpaid leave, he retreated to Chagford in Devon to write Brideshead Revisited, the first of his explicitly Roman Catholic books.

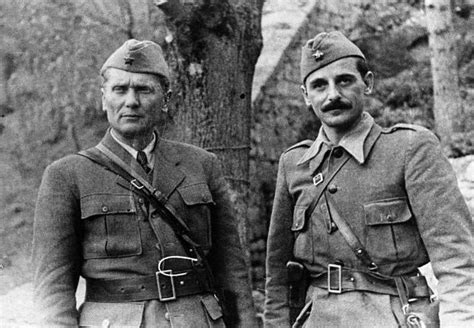

In July 1944 Waugh returned to service and was recruited by Randolph Churchill, a long-time acquaintance and occasional friend, to join the Maclean Mission to Yugoslavia. His relations with the Communist-led partisans were difficult, not helped by his insistence on referring to [Marshal] Tito as she. His chief interest became the welfare of the Roman Catholic church in Croatia, which he believed was suffering at the hands of the Communists and the Serbian Orthodox church. After his return to London in March 1945 his report was suppressed by the British Government in order to maintain good relations with Tito, now the head of communist Yugoslavia. In September 1945 he was released by the army, and returned to Somerset to Laura and his now five small children. The three volumes of his semi-autobiographical war trilogy, Sword of Honour, were published at intervals. between 1952 and 1961.

Men at Arms

In Men at Arms [pub. 1952], the first of the trilogy. Guy Crouchback, in his mid-thirties, [Waugh himself was 36 when the war broke out], from an old Catholic family, is determined to get into the war. It is essentially a question of honour, the need to prove himself. He takes a commission in the Royal Corps of Halberdiers, a thinly disguised portrait of the Royal Marines. Waugh’s move in January 1940 to Kingsdown Camp in Kent, a cavernous Victorian villa surrounded by the asbestos huts of a former holiday camp, caused his spirits to sink. But Kingsdown provided excellent material for a novel. Here Waugh encounters the formidable Brigadier Albert Clarence St. Clair-Morford: “He is like something escaped from Sing-Sing and talks like a boy in the Court Form at school – teeth like a stoat, ears like a faun, eyes alight like a child playing pirates, “We then have to biff them, Gentlemen”.” The Brigadier appears in an affectionate heroic guise as Brigadier Ritchie Hook in Men at Arms.

Another prominent character is Crouchback’s eccentric fellow officer, Apthorpe, memorably played by Ronald Fraser in the 1967 television adaptation. Apthorpe’s upbringing and pre-war life in Africa are surrounded by mystery. In an episode of high farce there is a battle of wits and military discipline between the Brigadier and Apthorpe over the latter’s mahogany thunder-box [portable toilet]. Before going overseas Crouchback attempts to seduce Virginia, from whom he is divorced, knowing that in the eyes of the Catholic Church she is still his wife. She turns him down.The book all ends tragically when the Halberdiers finally see action in the abortive Dakar affair. Apthorpe dies in hospital in Freetown, supposedly of a tropical disease. When it transpires that Crouchback had smuggled a bottle of whisky in for him, Guy is sent home having blotted his copybook. There are wonderful moments and comic characters. But I find that the overall sense is one of wistfulness.

Officers and Gentlemen

This is the second volume of Sword of Honour trilogy [pub. 1955]. After the abortive Dakar escapade, Guy is transferred to a Commando unit training on the Isle of Mugg. The unit is commanded by Tommy Backhouse, for whom Virginia had left him. There is plenty of whisky and high-stakes cards with fellow members of Turtles [based on Whites]. His fellow trainees include Ivor Claire, whom Guy admires as the flower of English chivalry. And also the seedy Trimmer, a former hairdresser on trans-Atlantic liners who becomes an improbable war hero. In a Glasgow hotel Trimmer embarks on an affair with Virginia, a former customer on the pre-war liners.

The high comedy turns to tragedy as Guy is involved in the humiliating defeat and withdrawal from Crete. Guy performs well, but no-one else emerges with much credit. He escapes from Crete in a small boat alongside the disquieting Corporal-Major Ludovic. Once back in Egypt Guy comes under the protection of the beautiful and well-connected Mrs Stitch [clearly based on Diana Cooper] who reappears from earlier novels. She arranges for him to be returned slowly to England, partly in order to avoid difficult questions being asked about Claire, apparently a deserter. The book ends with Guy back in London, asking around in his club about a suitable job.

Unconditional Surrender

This third volume of the Sword of Honour trilogy was not published until 1961, some fifteen years after the end of the war. After the Crete debacle Guy Crouchbank has lost much of his idealism. He is injured while parachute training at a centre run by the increasingly paranoid Ludovic. Who is afraid that Guy will expose his behaviour in the withdrawal from Crete. During his two years at HOO HQ in London Guy is brought back into contact into contact with his former wife Virginia, now pregnant by Trimmer. The couple remarry before he is posted to Yugoslavia, where his Catholic faith is offended by the Communist take-over. Guy tries ineffectively to minister to a ragged group of Jewish refugees, who then suffer because of his contacts with them. In London Virginia gives birth to Trimmer’s child, before she and Uncle Peregrine are killed in an air-raid.

In a short epilogue, set against the Festival of Britain, Guy has remarried, to Dominica Plessington, the daughter of an old Catholic family. I think we are to assume that Trimmer’s child will succeed as Guy’s heir. [Though different editions of the book have slightly different postscripts.]

Reaction to the books

Reaction to the books was mixed. Men at Arms won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize in 1952. Reviewers were generally favourable. But Cyril Connolly, one of Waugh’s few male friends [caricatured in the trilogy as Everard Spruce], writing in the Sunday Times, complained that the middle part of the book was dull and that Apthorpe was an unfunny private joke. Waugh himself while writing the book had referred to it as ‘Mrs Dale’s Diary’, a BBC radio soap of the time [to which my maternal grand-mother was addicted].

Progress was slow on the two subsequent volumes. Waugh was financially secure but maintained an extravagant rate of expenditure, and was looking to his war saga to finance his old age. Waugh was a commercially successful writer, and when Officers and Gentlemen appeared, it sold 26, 000 in the first month. Reviews were mixed. Cyril Connolly spoke of “a benign lethargy, which makes for slow reading”, while praising the latter sections on Crete. Waugh wrote to Maurice Bowra, “I am awfully encouraged that you like Officers and Gentlemen. The reviewers don’t, fuck them.”

By the time Unconditional Surrender appeared, in 1961, reviewers were uncertain what to expect. Waugh himself was “as successful, complacent, and vindictively dotty as ever” [Martin Stannard’s verdict]. His last two books, an anthology of his pre-war travel writing, When the going was good, and Love among the ruins had been dull, and his gifts as a writer seemed like his health to be in decline. At the age of 50 Waugh was old for his years, selectively deaf and rheumatic, and reliant on drugs to counter his insomnia and depression. Disturbingly his son Bron, author of the successful first novel The Foxglove Saga, seemed to be overtaking him in the public eye. Journalists were already writing about Waugh Père et Fils.

Reviewers again divided into two camps, with arguments for and against Waugh’s vision of the war and the world. Kingsley Amis and Philip Toynbee again attacked him for his social prejudices and his snobbery. But Cyril Connolly, while expressing reservations about the “biliousness of Waugh’s gaze” [cue Everard Spruce], was moved to read all three volumes and declared that “the cumulative effect is most impressive, … … unquestionably the finest novel to have come out of the war”. He even revised his opinion of Officers and Gentlemen, describing it as “magnificent”.

Personally I think the books are the best of Waugh’s fiction. The are some parallels with Brideshead, but with rather less of the snobbish nostalgia. Now there is a rich cast of characters: the socially inept Apthorpe, the all action military hero Ritchie Hook, the impostor Trimmer. And Guy’s bachelor uncle Peregrine, who mistakenly thinks that Virginia has designs on him. The episodes of chaotic HOO training on a Scottish island, the Isle of Mugg, and the unsuccessful hunt for an abortionist in wartime London remind us of Waugh’s gift for farce.

Guy Crouchback is a decent man, a melancholic [in Yugoslavia he confesses to a priest that he wishes for death], who chafes at the inactivity and bureaucratic incompetence of war when he wishes to be leading his men into battle. Like Waugh himself, Guy’s failings as a military man, and the failures of the operations in which he is involved – Dakar and Crete, contribute to his growing sense of disillusionment. His Catholicism makes him reluctant to embrace Stalin as an ally, and he is concerned about the future for his co-religionists in Tito’s Yugoslavia. When the war ends with a great victory over Nazism Guy shows no signs of elation. He regrets rather that he had once imagined that private honour would be satisfied by military service and war. Guy’s marriage and his adoption of Trimmer’s child means that the Crouchback line will continue. But it is not clear whether there will be room for the old-fashioned virtues of loyalty and honour and decency in the coming post-war world. Guy Crouchback, like his creator, found little that pleased him in the Britain of the late 1940s and 1950s. It all seems a long time ago. But I’m glad to have re-read the Sword of Honour trilogy which I first encountered some five decades ago..

Envoi

Susie and I went down to Birmingham for the weekend. The furtherest we have been from home this year ! And the furtherest we are likely to travel. We were there for my niece Léonies’s wedding to Carlos, a mushroom grower from the Canaries. [Disgracefully I have no photos of them.] It was very good to see the family. Whom we probably don’t see often enough. The weather forecast was for 30º-plus. But the train journeys went very smoothly, both down with Cross Country Trains and then back up with Avanti West Coast. We had booked Passenger Assistance in advance which worked well. But our helper when we arrived back at Edinburgh Waverley was apparently disappointed that I wasn’t my namesake from Coldplay.

We are now back home in Edinburgh, rejoicing in a temperate climate [there are stories of killer heatwaves around the Mediterranean], wondering whether to cut the grass, and fine-tuning the arrangments for a Celebration next month

June 2025