Drama on our doorstep yesterday afternoon. There was a major gorse fire on Arthur’s Seat, the volcanic hill just beyond the bottom of our garden. Our friends arriving from Lyon wondered if it was laid on for their entertainment. I set off to walk [limp] round the hill this morning. But it seems that some of the ground is still smouldering. A fire engine came past me in search of more water. And a police car told me that the top road was closed. So I walked to Duddingston instead.

Wilfred Thesiger: The Life of My Choice

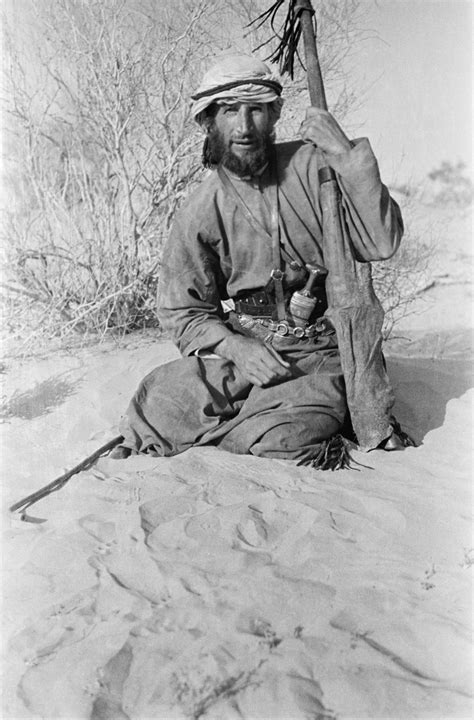

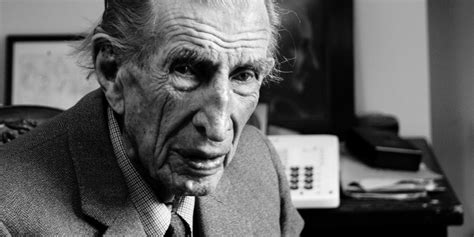

Wilfred Thesiger was the last of the great British eccentric explorers, a product of the latter days of the British Empire. I have been reading his autobiography, The Life of My Choice, published in 1987. It’s the life of the man of a previous age.

Thesiger was born in Abyssinia where his father was the British Minister in June 1910. He was the first British child to be born there. His father had served as honorary Vice-Consul in Van during the Armenian massacres, had fought in the Boer War 1900-01 with the Imperial Yeomanry, and then rejoined the Consular Service to serve successively in Belgrade, St Petersburg, and Boma in the Belgian Congo. In 1909 he was appointed Minister in Addis Ababa. From his parents the young Thesiger inherited a close friendship with Ras Tafari, the future Emperor Haile Selassi, and a deep and abiding love for Abyssinia and its peoples. When he came to England for school in 1920 he found it strange to be in a country with no hyenas, no kudos, no oryx, and no eagles. He was the only boy at his prep school, St Aubyn’s, who knew nothing about cricket, and he was beaten regularly by the sadistic headmaster. During his second term his father died suddenly of a heart attack at the age of forty eight. His mother took a country house in remote Radnorshire.

Thesiger was at Eton, and then went up to Magdalen College, Oxford in autumn 1929.He boxed for Oxford for four years as a light-heavyweight winning three times against Cambridge. In the October 1930 he returned to Abyssinia as Honorary Attaché to the Duke of Gloucester to attend the coronation of Tafari as the Emperor Haile Selassie. Also present as a journalist was Evelyn Waugh, of whom Thesiger had never heard. “I disliked his grey suede shoes, his floppy bow-tie and the excessive width of his trousers; he struck me as flaccid and petulant and I disliked him on sight. Later he asked me if he could accompany me into the Danakil country, where I planned to travel. I refused. Had he come, I suspect that only one of us would have returned.”

After graduating at Oxford Thesiger returned to Abyssinia for a year. His first expedition was to explore the land of the Danakil, a murderous tribe among whom a man’s status depended on how many men he had killed and castrated. It was a ground-breaking journey made in the company of a small group of natives including armed soldiers. Thesiger had only rudimentary Amharic and basic Arabic, and relied on Omar, his trusted Somali headman. “Omar … would have been upset if I had shared meal with the camel-men … I had grown up accepting our servants as subordinates, distinct in colour, custom, and behaviour”.

After this first expedition Thesiger did a four-month course in Arabic at SOAS, and went out to join the Sudan Political Service, travelling up the Nile via Cairo and Luxor. From January 1935 he worked in the Sudan, initially based in Kutum in Northern Darfur, where he and one other official administered an area of sixty thousand square miles, inhabited by a mix of Berber, African, and Arab tribes. His role involved extensive travelling around the region, mainly by camel, building relationships with tribal chiefs, and dispensing justice. And shooting lions which were then regarded as troublesome vermin by Darfur herdsmen. Thesiger remained in Sudan until the outbreak of the Second World War. In 1938 he made an expedition to Tibesti, the little known mass of mountains on the border of Chad and Libya, which extend two hundred and fifty miles from east to west and contain the highest peaks in the Sahara. Again Thesiger travelled by camel with a small group, Idris Daud, his teenage headman and five other Zaghawa tribesmen. In remote French Equatorial Africa a local chief warned that Britain’s policy of allowing uncontrolled immigration of Jews into Palestine was laying up troubles for the future. A prescient warning from an unlikely source.

When war breaks out Thesiger is commissioned as a Bimbashi in the Sudan Defence Force. He serves under [Major] Orde Wingate, at that time best known for leading Jewish night squads against Arab guerrillas. Wingate was a passionate Zionist, regarded by military authorities as a security risk for passing information to Jewish leaders. Thesiger describes him as arrogant, ill-disciplined, and resentful of authority; an idealist and a fanatic. Who would have been better suited to the time of the Crusades. Later in the war Thesiger served with the SOE [Special Operations Executive] in Syria and with the SAS [Special Air Service] and the Long Range Desert Group in North Africa. In 1943 he resigned his commission to work as Political Advisor to Crown Prince Asia Wossen.

Thesiger’s best-known expeditions took place after the war. Between 1945 and 1950 he made unprecedented travels across the Empty Quarter of Saudi Arabia, sharing the vanishing way of life of the Bedouin tribesmen. And he later lived among the indigenous peoples of the marshlands of southern Iraq. These experiences are described in his two best-known books, Arabian Sands [1959] and The Marsh Arabs [1964]. Both of which I read a long time ago. In addition he travelled extensively in Iran, French West Africa, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. He spent his latter years living among the Samburu tribesmen of Northern Kenya and writing a succession of travel books. Critics say that the quality of his books deteriorated. He died in Surrey in 2003 leaving a vast collection of photographs and negatives to the Pitt-Rivers Museum in Oxford.

Thesiger was a child of the British Empire. His father presided over the mud huts of the British Legation in Addis Ababa. His uncle was Viceroy of India. As a six-year-old he experienced the spectacular victory celebrations as Haile Selassie marked his conquest of the old ruler and received homage from the Abyssinian nobility and some sixty thousand fighting men. These early experiences gave him “a lifelong craving for barbaric splendour, for savagery and colour and the throb of drums, and … … a lasting veneration for long-established custom and ritual, from which would derive later a deep-seated resentment of Western innovation in other lands, and a distaste for the drab uniformity of the modern world.” Thesiger’s motives for enduring the torments of travel were complex and intriguing. He hated the materialism of the West and sought an alternative in the austerity of traditional Arab life. He wanted to experience freedom and comradeship, to test himself during hardship and danger in unexplored countries

Women are conspicuously absent from this book. Apart from his much loved mother on whom he doted. Like T.E. Lawrence, whom he greatly admired, Thesiger had close relationships with young Arab servant boys. In his Seven Pillars of Wisdom Lawrence had glorified “friends quivering together in the yielding sand with intimate hot limbs in supreme embrace”. Equally Thesiger’s books contain seductive photos of androgynous young Arabs. When a Vanity Fair interviewer boldly asked if he had been in love with them, he replied that he did love them, “as long as you don’t mean physical love”. His attachment was “the sort of love you give to your brothers and your family.” Some modern commentators are doubtful about this firm rejection of homosexuality. But I think for Thesiger celibacy was probably part of the penance of the desert. Which for him, as for Lawrence, was a place of purification. Remote from the uncleanness of the ‘civilised’ world.

Remembering Mrs Minchin

I’ve never been to Ethiopia and my personal experience of the British Empire is nil. But -when I was at Christ Church, Duns, in the 1990s, one of my regular Home Communion visits was to Mrs [Kathleen Winifred] Minchin, who lived at Easter Cruxfield, an isolated farmhouse out in East Berwickshire. Mrs Minchin [it never occurred to me to call her anything else] was a child of the Empire. Her father, Colonel William Molesworth CBE, had been Governor General of the Andaman islands and was subsequently Surgeon to the Viceroy. She had been born in Salem, Madras, but the family had a house in Poona. As child she was staying with her grand-parents in Queenstown in southern Ireland and recalled being taken out of the house to see the Titanic on her maiden voyage. Her only brother, William ‘Moley’ Molesworth, flew with Albert Ball in the Royal Flying Corps, was credited with 18 kills and won the MC and Bar.

She herself was married, in Simla, to Alfred Alyson Minchin, described by her as ‘a box wallah’. [I think her father would have preferred her to have married an Army Officer !] The marriage foundered, and she came home to Berwickshire to live with her father to whom she was very attached. Of their two children the younger , I think, [and favourite] son, Lieutenant Henry Desmond Penkivel Minchin, was killed fighting in Normandy in 1944. I used to have a slim volume of his not-terribly-good poetry. Privately published. There is an idealised portrait of him in a stained glass window in Christ Church. Mrs Minchin lived by herself in this big house until March 1998, and when she died at the age of 102, I buried her in the family plot at Preston [Edrom] in Berwickshire. I wrote an obituary of Mrs Minchin for The Berwickshire News when she died, but her surviving son Pat thought it best ‘not to make a fuss’ and so it was not submitted for publication. Mrs Minchin’s only grandson, Ronald, had died in his mid-fifties a couple of years earlier. Most probably from alcohol poisoning. Tragic. I took his funeral too.

August 2025

Thank you for a fascinating piece of history! I hope your Arthur’s Seat is no longer smouldering. There is an Arthur’s Seat in Victoria Australia on the Mornington Peninsular, a 304-metre granite hill but I have never walked it. Maybe I should. G. 🚶♀️

LikeLike