After finishing the Zeldin book [see TaGD – 20], I thought that I would look again at Alistair Horne’s book The Fall of Paris: the Siege and the Commune. Horne was a journalist, biographer, and European historian, who died in 2017.

My copy of the book first published in 1965 is a bit water damaged after a long spell in the garage. Unfortunately the subsequent two books in Horne’s trilogy, The Price of Glory: Verdun 1916 [1962] and To Lose a Battle: France 1940 [1969] have both disappeared; I think they too both succumbed to water damage.

The Siege

The Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 was a disaster for the French. In July 1870 France declared war on her neighbour; partly because the countries fell out over the vacant throne of Spain, and partly because France felt threatened by the growing power of Prussia. On July 28th Louis-Napoleon rode forth in command of his armies. Within six weeks the divided French armies were defeated on both sides of the Vosges, at Woerth and at Spicheren; Bazaine’s army was besieged at Metz; MacMahon’s army surrendered at Sedan; and Bismarck imposed harsh terms on Louis-Napoleon who was sent into imprisonment in Germany. The Prussian armies under Moltke advanced rapidly on Paris, and by the end of September the city was under siege. It was now cut off from the rest of France. “It is in Paris that the beating of Europe’s heart is felt”, wrote Victor Hugo, a vigorous septuagenarian, “ Germany extinguishing Paris … Can you Germans become Vandals again; personify barbarism decapitating civilisation.”

General Trochu, aged fifty-five, had been recalled from an obscure command in the Pyrenees to form the new XII Corps, and then to become Military Governor of Paris. When in September amid chaotic scenes at the Hotel de Ville Gambetta, standing on a window sill, proclaimed the Republic, the post of President was offered to Trochu. Who accepted it with no great enthusiasm. The city of Paris was surrounded by an enceinte wall, some thirty feet high, divided into ninety three bastions linked by masonry ‘curtains’; and behind the moat were a chain of powerful forts equipped with powerful guns. The line of forts filled out a circumference of some forty miles. Within the city there were some 60,000 troops, some of whom had escaped from Sedan and elsewhere. And there were, very soon, some 350,000 members of the National Guard; a great mass of untrained [working] men, attracted by the pay of 1.50 francs a day, and the right to elect their own officers. Notionally Paris was a powerful armed fortress. But there was no strategy as to how their considerable assets were to be managed. Trochu himself was a military theorist rather than a man of action. Washburne, the American Minister, who was received by the new President in his slipper and dressing-gown, thought “he did not look much of a soldier”.

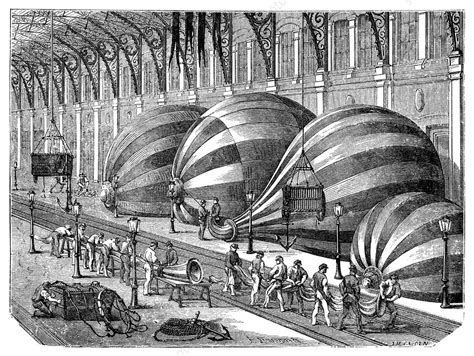

All one ever remembers of the siege of Paris are the balloonists and the rats. Balloons had always been a French thing. Since De Montgolfier’s first hot-air balloon of 1783; a perilous device in which the passengers had to stoke a fire of straw and wood directly below the highly inflammable paper envelope. When the siege of Paris began there were only seven existing balloons, but a series of balloon making workshops were set up across the city and a highly profitable Balloon Post was established.

Balloons took off at the rate of two or three a week, either from Montmartre or from outside the Gare du Nord. The problem of course was this was a one-sided means of communication. And that the balloons were blown to every corner of France. When the idea was mooted in September of ballooning a delegate to Tours, Gambetta, the Minister of the Interior, was one of the few volunteers. Gambetta left Paris on October 7th and after an eventful flight arrived forty-eight hours later in Tours where he declared himself Minister of War. Altogether some 65 manned balloons left Paris during the siege; six landed in Belgium, four in Holland, two in Germany, one in central Norway, and two were lost at sea. The knowledge that the city was not entirely cut off from the rest of the world served to restore some Parisian morale.

As half-hearted attempts to break out of the city failed, the lack of news was replaced by a lack of food. Hunger became a real problem. Goncourt noted “People are talking only of what they eat”; and found Théophile Gautier lamenting that “he has to wear braces for the first time, his abdomen no longer supporting his trousers”. Cheese, butter, and milk were all little more than a memory; the cattle and sheep had vanished from the city; and fresh vegetables had run out. The zoos were forced to surrender their precious inmates: Hugo was sent some joints of bear, deer, and antelope by the curator of the Jardin des Plantes; and two young elephants, Castor and Pollux, were bought by Roos, the wealthy proprietor of the Boucherie Anglaise. Horse-meat became commonplace, as even valued race-horses ended their days at the butchers. Horne records that the signs ‘Feline and Canine Butchers’ made their debut. The journalist Henry Labouchère reported without comment that he had met a man who was fattening up a large cat for Christmas Day, intending to serve it “surrounded with mice like sausages”. The rat was the most fabled animal of the Siege of Paris, and from December a good rat-hunt was a favoured occupation of the National Guard.

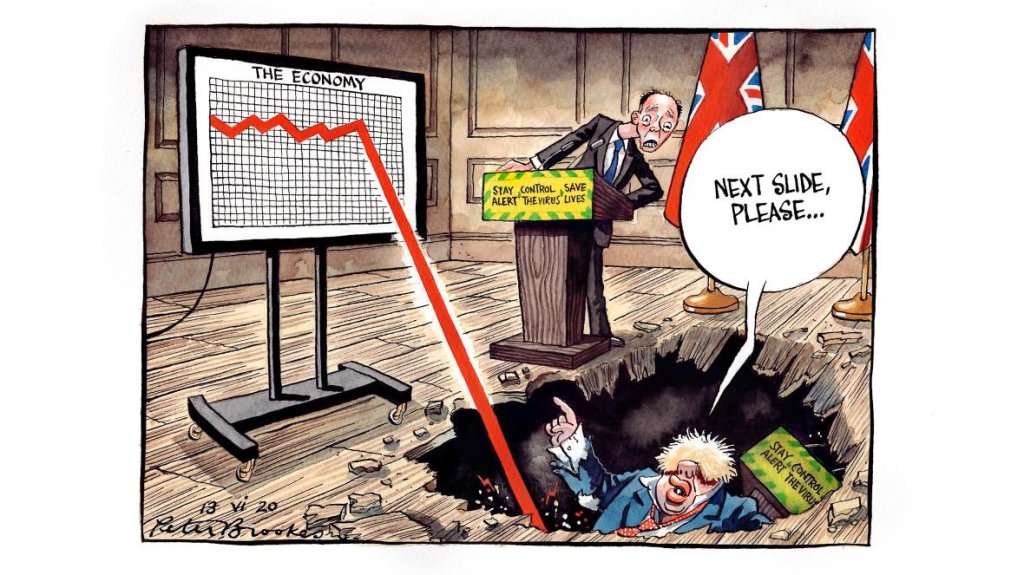

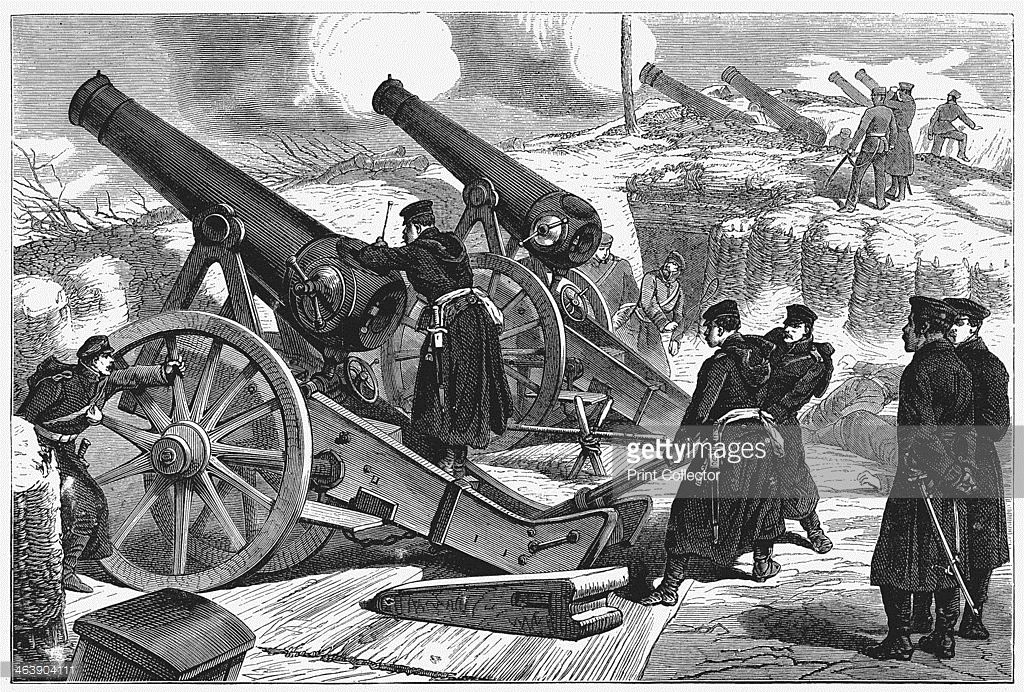

German bombardment of the southern forts began in January. The nightly bombardment did relatively little damage, but there was great anger when six small children were killed by a single shell. Fuel shortages in the winter months, malnutrition, and diseases, both smallpox and typhoid, began to take their toll. Another projected sortie at Buzenval failed dismally, for which the leadership was violently criticised by the Mayors, led by Clemenceau of Montmartre. While the pious Trochu prayed for deliverance, his influential deputy, Favre, now favoured capitulation. On January 27th Favre secretly met with Bismarck in Versailles to negotiate a cease-fire, pending the drawing up of a definitive peace treaty.

The Commune

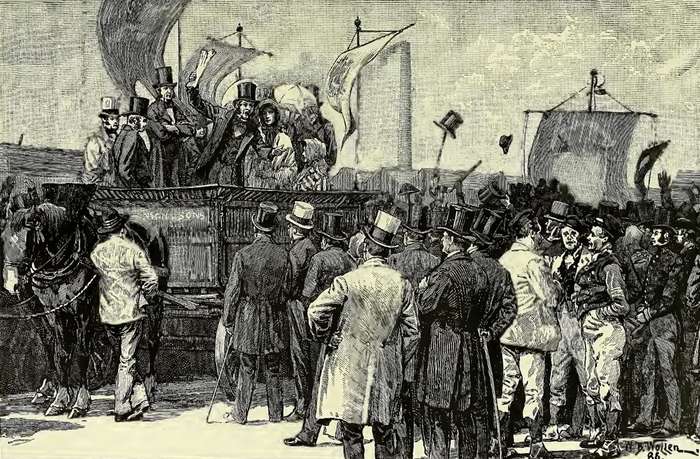

Favre’s armistice was received in Paris with a mixture of rage and stupor. Needed foodstuffs poured into the city, but Republican Paris felt betrayed by the capitulation, and further betrayed by a February election which resulted in an overwhelming victory for the ‘list for peace’. A rift had opened up between Paris and the provinces, and this was aggravated by every step taken by the new administration headed by Thiers. On February 26th, the day that Thiers signed the Peace Treaty, mass demonstrations of the National Guard erupted across the city, and two hundred cannon were hauled from the artillery parks to Montmartre. An attempt by the French Army to retrieve the cannon failed, and General Lecomte and the elderly General Thomas were lynched by an angry mob. When Clemenceau saw what had happened he burst into tears; the only time the tough doctor-politician wept in public until the victory of 1918.

The government move on Montmartre and the killing of the two generals took everyone by surprise. But a group of National Guards led by Brunel marched on the Hotel de Ville, and, as the gendarmes and government troops melted away, 20,000 National Guards took possession of the building. As the government withdrew, legal authority in Paris passed to the Mayors of the twenty arrondissements. Heated discussions between the Comité Central and the mayors ensued, fighting broke out on the streets of the city, the rift between Paris and Versailles widened, and on Tuesday, March 28th, the Commune was officially declared at the Hotel de Ville.

“Now that our Commune is elected”, wrote Corporal Louis Péguret of the National Guard, “we shall await with impatience the acts by which it will make itself known to us. May God wish that this energetic medium … will procure for us genuinely honest and durable institutions”. All Parisians wondered what the Commune would do. In fact, what was the Commune ? Contrary to what many bourgeois believed, it had nothing to do with the Socialist International. The Commune came to power in 1871 with no ideology and no programme; other than looking back over its shoulder to 1793. There was certainly a sense that the working class had been swindled out of their inheritance of the Great Revolution. It was born partly out of general discontent with the poor social conditions under the Second Empire. “What is it to me”, someone asked in Goncourt’s hearing, “that there should be monuments, operas, cafe-concerts, where I have never set foot because I have no money ?” And there was also an element of demanding municipal independence for industrial Paris from the rest of predominantly rural France. In consequence the Commune was invariably riven with disputes between Blanquist socialists and radical Jacobins; between anarchists, intellectuals, Bohemians, Gambettists, and disgruntled petit bourgeois.

Disunity was the death of the Commune. The brave and capable Louis Rossel, a professional soldier, son of a Breton father and a Scottish mother, was appointed Minister of War, but was soon accused [wrongly] of treachery and deposed. A Parisian mob tore down the massive Vendôme Column erected by Napoleon I on the sight of the former equestrian statue of Louis XIV. The Paris house of Thiers was demolished and his belongings and works of art were carried away by the mob. Raoul Rigault the unsavoury Police Chief ordered the arrest of a number of ‘hostages’ including the Archbishop of Paris. Clemenceau and his fellow mayors, and other bodies including the Paris Freemasons, tried to open negotiations between Paris and Versailles. But all failed. Thiers’ unvarying response was: “Do you come in the name of the Commune ? If so, I shall not listen to you; I do not recognise belligerents … I have no conditions to offer”.

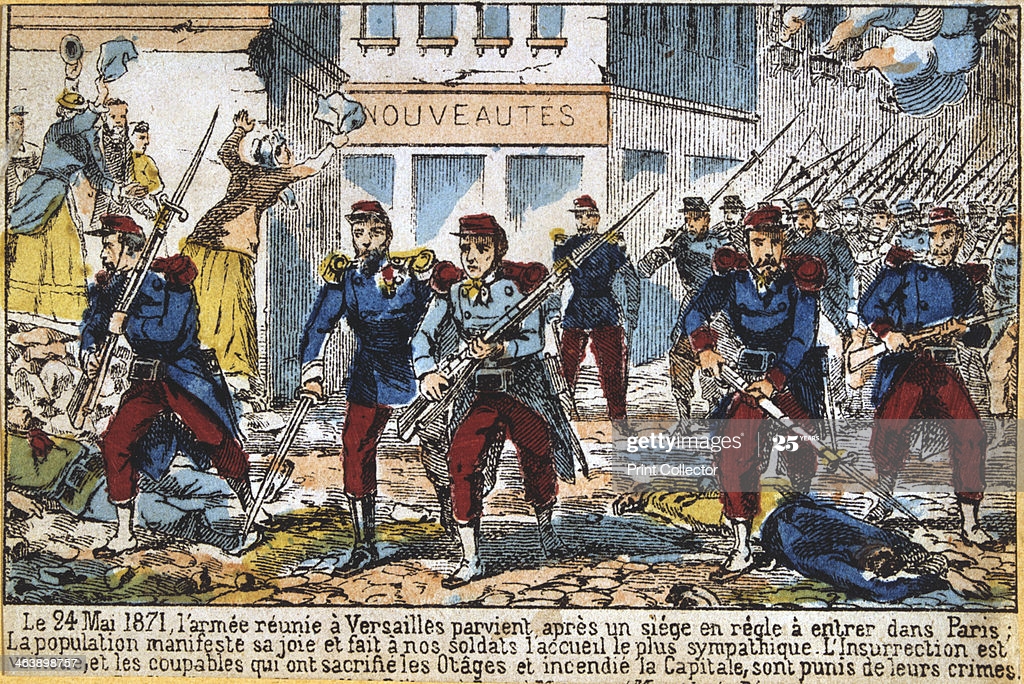

On May 21st Government troops entered the city through an unguarded gate at Point-du-Jour. Ten days of bloody fighting followed. A frenzy of energy seized the Commune and hundreds of street barricades were thrown up as the Versailles troops advanced steadily through the west of Paris. Small pockets of Communards fought bravely. Rumours of mass terror spread swiftly through the city’s inhabitants. It was widely believed that an army of pétroleuses were at large in the city flinging fire-balls through the windows of bourgeois houses. On the evening of May 24th the aged Archbishop of Paris and four other priests were shot in La Roquette prison. National Guards ripped open his body with bayonets, and threw it into an open ditch at Père-Lachaise cemetery.

The Communards were forced back towards Montmartre and towards Belleville. The leaders of the Commune were falling. The sixty-one year old Delescluze, moral leader of the Commune, an old style Jacobin, now dying of consumption, made his way to the Avenue Voltaire dressed in top hat, black trousers, and frock coat with a red sash round his waist; and was promptly shot on an abandoned barricade. There were savage killings on both sides. Many captured Communards were shot on the spot. The Prussians obligingly moved up 10,000 troops behind the Communards’ rear to cut off any possible escape eastwards. On Whit Sunday morning, May 28th, Thiers’s army moved in for the kill. On that day when they discovered the unburied body of the murdered Archbishop, 147 captured Communards were lined up and shot against the eastern wall of the cemetery.

On June 22nd the Paris-Journal implored: “Let us kill no more, not even murderers and incendiaries ! Let us kill no more !” The remaining Communards surrendered. But casual, incidental killing continued for several days. The estimated number of deaths during La Semaine Sanglante varies wildly. But responsible historians suggest that between 20,000 and 25,000 people were killed. Far more than in any battle of the Franco-Prussian War. Far more than were killed during the Great Terror of the French Revolution. All this killing in a city that had regarded itself just a short time earlier as the very Citadel of Civilisation.

The myth of the Commune

The siege of Paris fundamentally altered the balance of power in Europe; France was diminished alongside a resurgent, and united, Germany. And would not be restored until she regained the surrendered industrial areas of Alsace and Lorraine. The consequences of the Commune are harder to identify. The social achievements of the Commune during the brief two months of its existence were minimal. Frankel, one of its leading reformers, could point only to the abolition of night-work in Parisian bakeries.

But out of the fabric of the Commune Karl Marx created an enduring myth. In his powerful tract The Civil War in France, written from a safe distance away in north London, Marx celebrated the French working class as “the advance guard of the modern proletariat”. Marx’s whole-hearted support for the Commune split the International movement down the middle. On the one side, the nascent, moderate British Labour Party and the German Social Democrats; on the other, Lenin and the Russian Bolsheviks. The widely-read pamphlet transformed Marx from being an obscure German-Jewish professor to being the ‘Red Terrorist master-mind’. He helped create a heroic Socialist legend. The Mur des Fédérés in Père-Lachaise, where the 147 Communards were shot, is the focal point for left-wing demonstrations on May 28th every year.

The story of the Commune inspired a host of writers, including Emile Zola, Arnold Bennett, Jean Vautrin, and Umberto Ecco; and a variety of playwrights including Brecht and Adamov. I was fascinated to learn that, among the Commune inspired films, there is a 6-hour epic [unwatchable ?] by Peter Watkins called La Commune, shot in 2000 in a deserted factory on the outskirts of Paris. In a distant echo of the Commune balloonists, Alistair Horne notes that in 1964, when the first three-man team of Soviet cosmonauts took off, they took with them three sacred relics; a picture of Marx, a picture of Lenin, – and a ribbon cut from a Communard flag.

PostScript

Is there a museum in Paris dedicated to the history of the Paris Commune ? If so, I have never seen any mention of it. And the Institut Français in Edinburgh hadn’t either. If anyone who reads this knows better, do please let me know. I’d definitely make a pilgrimage to go and see it.

September 2020