I’m often given books as presents, and sometimes I don’t want to read them. A few years ago I was given Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty First Century. And although I would like to have read it, I didn’t actually want to open it. And it sat reproachfully unopened on the shelves for a couple of years before I took it along to the OXFAM shop. More recently I was given a copy of a commentary on the book of Job, written in French by a conservative reformed pastor. I have looked at the early pages. But I know that I won’t live long enough to read the rest of it. And I’m aware that it may not sell very fast in the Edinburgh OXFAM shop. On the other hand I have just read, with great interest, a book that I was given for my birthday last summer.

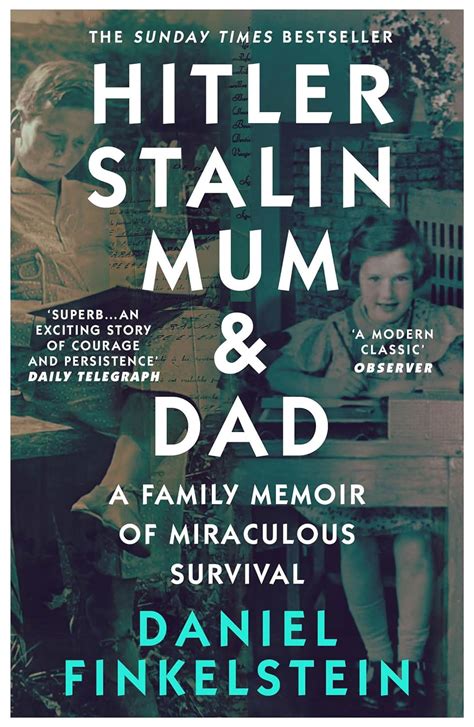

Daniel Finkelstein: Hitler Stalin Mum and Dad

I am not predisposed to like a book by a Tory member of the House of Lords [elevated by David Cameron in 2013]. Who is also a journalist, political commentator, and supporter and director of Chelsea football club.

[Aside. When did it became the norm for politicians to make known their football allegiances ? Did it start with Tony Blair, who claimed unconvincingly to have bunked off school to watch the Newcastle centre forward Jackie Milburn ? He didn’t; the dates don’t work. The prolific Alastair Campbell, onetime journalist and Blair’s right hand man, is known as a lifelong Burnley supporter. David Cameron claimed to be an Aston Villa supporter, but in an interview confused them with that other claret-and-blue team West Ham United. [Or CSBJ, the Bourgoin rugby club ?] Keir Starmer claims to be an Arsenal supporter, like Jeremy Corbyn and Pritti Patel. He used to have a season ticket at the Emirates, though he may not have paid for it. Rishi Sunak supports Southampton – who have just been relegated. That sounds about right. I don’t think that Clem Attlee or Harold Macmillan ever talked about standing on the terraces at Highbury or at Villa Park.]

But Daniel Finkelstein’s family memoir is an extraordinary and gripping book. He tells the story, in some detail, of how his parents and grand-parents survived events in Europe during the 1930s and 1940s. His maternal grand-father, Alfred Wiener, was a German Jew, born in 1885 in Potsdam. He was committed to the development of a modern liberal Germany and of modern Judaism, and saw these things are mutually supportive. After the First War, in which he fought for Germany and was decorated, he became General Secretary of the CV, the Central Association of German Citizens of the Jewish Faith. The CV campaigned against anti-Semitism and sought to develop ideas of tolerance, liberalism, and social equality. But after Hitler became Chancellor in January 1933, Alfred realised that he would have leave Germany. He settled in Amsterdam where he was joined by his wife and their three daughters. The youngest, Mirjam Emma Wiener, Finkelstein’s mother, was born in Berlin in June 1933.

His paternal grand-father, Adolf Finkelstein [Dolu] was born in Lwow, in Poland, in 1890. The Finkelsteins were a wealthy Jewish family, fluent German speakers, partners in the dominant iron and steel business, who also owned property in Vienna. Prior to the creation of an independent Polish state, Lwów had been a provincial centre of the vast Austro-Hungarian Empire. Half of its population were Polish, the other half divided equally between Jews and Ukrainians. Dolu married Luisa, the daughter of wealthy landowners, and they had one son, Ludwig, Finkelstein’s father, who was born in 1929. The business prospered and Dolu because known as ‘The Iron King’.

What happened next is an epic tale of survival. Timothy Snyder and Anne Applebaum have written about the suffering of central European Jews under Nazi Germany and Communist Russia, under Hitler and Stalin, the two genocidal dictators of the twentieth century. Finkelstein retells the story in terms of his own ancestors.

Alfred Wiener spent his years in Amsterdam assembling documents and data about persecution in Nazi Germany. The collection eventually became the Wiener Library. He himself relocated again to London, and then to the United States, before the war broke out. He was preparing to bring over his wife and daughters when Germany invaded the Netherlands. His wife Grete and their three daughters are trapped in occupied Amsterdam. Their friends included Anne Frank and her family. Of their predominantly Jewish neighbours in Jan van Eijckstraat 90 were murdered in the camps, in Auschwitz and Belsen, in Sobibor and Mauthausen. In June 1943 Grete and her girls were rounded up and sent first to Westerbork camp and then to Bergen-Belsen.

Three years earlier, in April 1940, Adolf Finkelstein had been arrested in Lwów by Soviet troops and militia as part of a bigger round-up. He was held in prison in Poltava and in Starobelsk, and was then sent north to a Siberian gulag, a labour camp, near Ukhta. Very shortly afterwards the NKVD came for Adolf’s wife, Luisa, and their son Ludwig, and they were forcibly relocated to a remote settlement in eastern Kazakhstan to work on a sovkhoz, a Soviet state farm. It was a place of hunger and death. There Ludwig and his mother along with some 100 other exiled Poles survived the freezing winters in a primitive shed built from cow dung.

That any of his ancestors survived, and that some of them were reunited after the war, is a miracle. Though that is not a word that Finkelstein uses. It is a long story, and I was grateful for the four family trees at the start of the book. The book overlaps thematically and chronologically with Philippe Sands’ East West Street. The authors share a common past in Lwów/Lviv, and Finkelstein acknowledges that they are almost certainly cousins.

Through the detailed story of the Wiener and Finkelstein families, the book underlines the almost unbelievable suffering of the European Jews in the 1930s and 1940s. It evenhandedly accuses both Hitler and Stalin of awful crimes against humanity. Very unfortunately, lingering western guilt about doing too little too late to halt the Nazi holocaust means that world leaders are again doing too little to bring an end to the Israeli offensive against the Palestinians, Which to me looks very like ethnic cleansing. As tens of thousands of Palestinian women and children are sacrificed to save the political career of the odious Benjamin Netanyahu. The book ends with the survivors leading unremarkable lives in the respectable north London suburbs of Hendon and Swiss Cottage.

As I write this, I realise how little I was affected by any of this history when I was younger. I remember that when I was hitchhiking in Europe in the summer of 1963, I went out for a drink in Munich with a Jewish girl from Canada. Who told me that 17 of her immediate family had died in the camps. But I didn’t really take in the horror, and I didn’t make much of it at the time. And I can’t now remember her name.

Envoi

Susie and I continue to limp around on poles, like senior citizens practising for a three-legged race. Unusually, on two successive Sundays, I have been preaching out of town at St Anne’s Episcopal Church, Dunbar. Squeezing into a tiny Car Club car is an effort. But it was lovely on sunny mornings by the sea. And the congregation were very welcoming. Closer to home the roses are coming out, the garden is as good as it gets, and has required regular watering. We have been casting about trying to find a [replacement] skiffle band for a Celebration in July. And we are looking forward to seeing Craig and the girls here next week. It will be Amelia’s fourteenth birthday on Wednesday.

May 2025

I’m

LikeLike

That’s a very cryptic comment, Madge. Are you OK ?

LikeLike