Changing Places

Just typing those words brings up odd memories and connections. Changing Places was the title of a very funny campus novel [of 1975], in which the conformist University of Rummidge [Birmingham] lecturer, Philip Swallow, does an exchange with the ebullient, cigar-chewing Euphoria University [Berkeley] academic. Morris Zapp. But in a very different culture Changing Places is now the name of a pressure group that campaigns for fully accessible public toilets for people with profound and multiple disabilities. And also for old people. Perhaps they are the same group ?

I’m not wanting to write about either of those things. Instead, aware that it is almost exactly a year since we went to do locum ministry in Ankara, I have been reading a book which I first saw there in the chaplaincy flat; Twice a Stranger by the journalist Bruce Clark. It is an excellent book.

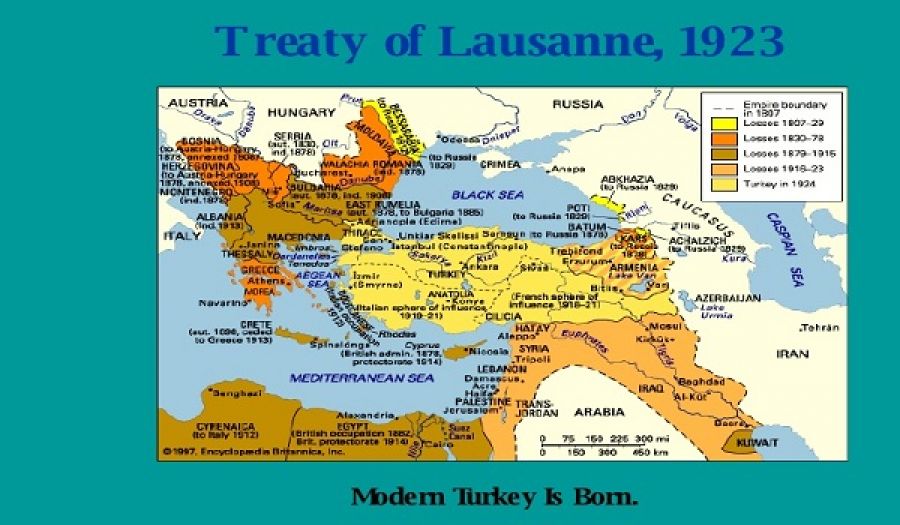

The treaty of Lausanne

After the 1914-18 war the situation in Greece and Turkey was very confused. In the culturally and confessionally diverse Ottoman world, modernity led not to integration but to ethnic division. People and religions were forced to live separately because no way of co-existence could be found.

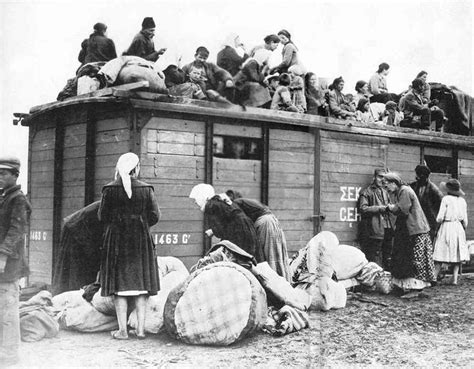

The separation was a solution to an immediate political crisis. But population transfer was the culmination of a long historical process. The Sultans’ retreat from Europe began with the Serbian revolt of 1804 and the creation of a new, self-consciously Christian kingdom of Greece in 1829. Greece was poverty-stricken. Ambitious Ottoman Greeks found more opportunities elsewhere, in Anatolia. But conflict engulfed Anatolia in 1919 when a Greek expeditionary force [supported by European powers and by Lloyd-George] invaded the nascent Turkey and occupied Smyrna. In 1922 the Turkish Republic under Mustafa Kemal drove the Greeks back into the sea. New borders were drawn up. Economic assets were distributed. “Henceforth, it was determined, Greece would be an almost entirely Orthodox Christian country, while in Turkey the overwhelming majority of citizens would be Muslims.” The terms of the divorce were contained in the Treaty of Lausanne in January 1923. Which allowed for substantial population exchange: some 400,000 Muslims in Greece [speaking Greek, Albanian, and Bulgarian as well as Turkish] were deported [back to Turkey]; and some 500,000 Turkish-speaking Christians who had lived in Anatolia were shipped to Greece.

The modern societies of Turkey and Greece were significantly shaped by this exchange. Anatolia lost virtually all its traders and entrepreneurs, and most professional people and skilled craftsmen. While Athens still has a significant minority of people from Asia Minor origins. A new dogma of nationalism emerged. Before 1923 ‘Greek’ and ‘Turkish’ had little meaning. But “the treaty of Lausanne … was inspired by a new way of looking at human society; one that dealt in hard, hermetically sealed categories, and insisted that every individual and family must belong to one nation or the other and live within its borders.” Whatever they felt about being deported, the Christians of Anatolia and the Muslims of Greece were now remoulded as Greeks and Turks.

Who was responsible for this massive piece of social engineering. Clark identifies Eleftherios Venizelos, the dominant Greek politician of the time, and Fridtjof Nansen, the Polar explorer turned United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, as the main players. They knew that compulsory resettlement would cause hardship and suffering, but it seemed that population exchange on a huge scale was the only solution to a burgeoning humanitarian crisis.

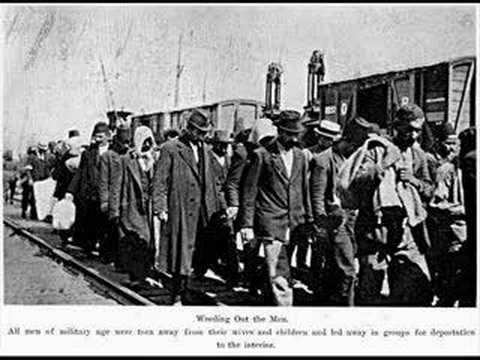

What happened ?

Bruce Clark traces the human stories of the people who were wrenched from their homes. He draws on interviews and the oral history of the people involved. There were difficult decisions to be made. The Pontic Greeks of Trebizond, a flourishing Greek port on the Black Sea, traced their origins to Greek colonists in about 700 BC. But in January 1923 Greek Orthodox families in Trebizond were told to leave their homes within one hour. Because of its location, Trebizond had had little direct contact with mainland Greece. More than elsewhere in Anatolia there was a close sympathy between Greeks and Turks. The Pontic Greeks had retained both their language and their religion. There were also tens of thousands of ‘crypto-Christians’, who straddled the boundaries between the Muslim and Christian faiths. The division between Muslims and Christians here was not clear-cut. The Greek-speaking population of Imera, a remote village in the mountains behind Trebizond, was isolated from Muslims and Turks. Forced into exile in Greece in 1923, they retained a nostalgic longing for their villages; displaying an ethnic and cultural ambivalence.

Liberal opinion in the west was horrified at the notion of compulsory expulsion of all Christians from the new Turkish state. So, Lord Curzon backed Venizelos in his claim that the Greek Orthodox population of Constantinople be exempted. On the understanding that the Patriarch’s rule was purely religious. In return for allowing 100,000 Greeks to remain in Constantinople, the Greeks allowed [roughly the same number of ] Ottoman Muslims to remain in western Thrace. There was an additional problem over the Turkish-speaking Christians of Cappadocia; an area with long-standing Christian traditions, where the distinction between ‘Greeks’ and ‘Turks’ was very unclear. It was initially thought that the Cappadocian Christians would be exempted. But then it was acknowledged that their presence in the centre of Turkey would be too problematic.

The outcome

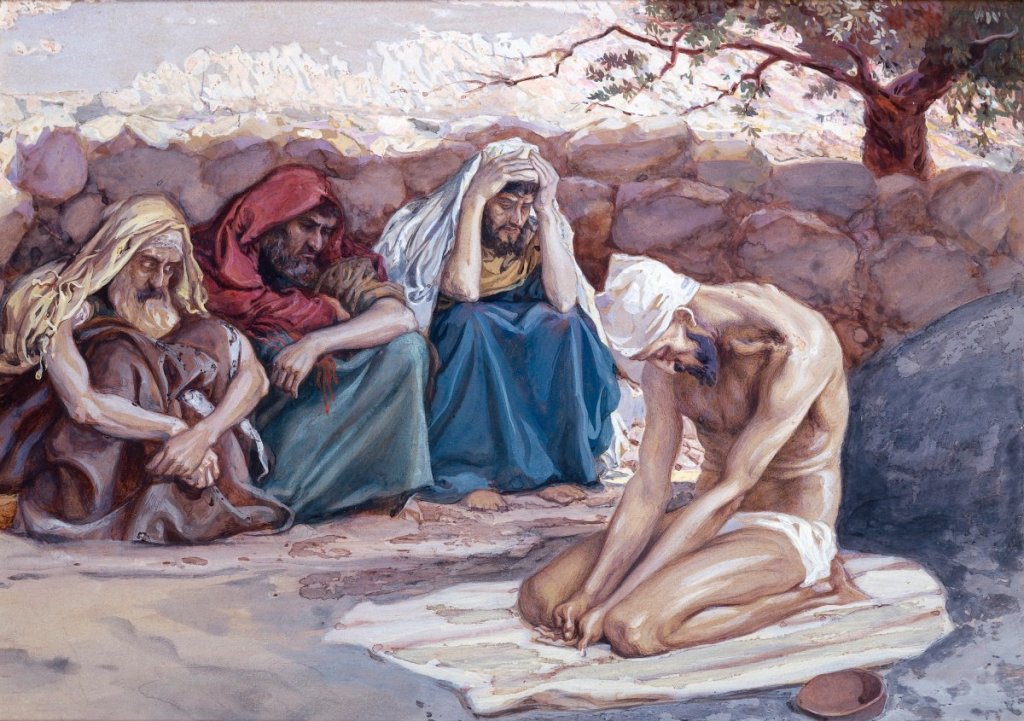

The compulsory population exchange caused a great deal of heartache and suffering. Many Anatolian Christians fleeing Smyrna and Trebizond were housed temporarily in the Selimye barracks in Constantinople; they experienced hunger, were overcrowded, and were ravaged by smallpox and by typhoid. But it ‘worked’ in that it contributed in both countries to the forging of a more-or-less homogenous nation-state. “Compared with any major country in western Europe, Greece and Turkey are fairly homogenous countries.” The vast majority of Greek citizens speak Greek and adhere, at least nominally, to Orthodox Christianity. The vast majority of Turkish citizens speak Turkish and adhere to Sunni Islam. On the Turkish side, with a population of 70 million, the only exception are the Kurds, who may number 10 million, and who have never been fully incorporated into the Turkish Republic.

“It is a hard fact of modern Greek and Turkish history”, Clark concludes, “that this huge and ruthless project in social engineering was more successful than otherwise …” And the project was certainly helped by on both sides by a single faith. Even though the infant Turkish Republic was determinedly secular. [The secularist founders of the Republic of Turkey would be disappointed by recent developments.] Equally the rites, sacraments and bonding influence of the Greek church have made a significant contribution to the holding together of the modern Greek state.

One issue that was not settled by the Treaty of Lausanne was Cyprus – which was then a British colony. Cyprus was a running sore from the 1950s. In the summer of 1974 a coup by Greek and Greek-Cypriot ultra-rightists triggered a Turkish invasion. Leaving a divided island.

In the 21st century it is no longer possible for Greece and Turkey to remain neatly divided and hermetically sealed countries. In Greece half the wage-earners have migrated to Germany to work, and many houses are being bought as holiday homes for north Europeans. Greece now has a diverse labour force, of whom 20% may be non-Greek-speakers, The Lausanne guiding principle of ‘Greece for the Greek Orthodox Christians’ may be unsustainable in the 21st century.

Similarly, if Turkey continues to pursue its ambition to join the European Community, it will no longer be able to impose a single, narrowly defined model of ‘Turkishness’ on all its citizens. For Turkey’s nationalist establishment, every concession to Brussels means surrendering some part of the Lausanne principles on which the republic is based. “It is baffling and infuriating” for them, Clark notes, “to be told by European organisations that they must dismantle the post-Lausanne republican order and go back to the older notion that more than one language, culture, and religion can exist under the same roof”. But as globalisation and liberal capitalism advance, they are bringing a different concept of citizenship to the partially modern, partially traditional societies of Turkey and Greece. But some people are nervous that President Erdogan may think that 2023 is the time to renege on some aspects of the Lausanne agreement.

The relevance in our world today

The issue at the heart of the Lausanne negotiations, that of how to deal with an ethnic and linguistic minority within one country, is a recurrent issue in the history of the past century. The existence of the Sudeten Germans was the trigger for Nazi Germany’s two-stage annexation of Czechoslovakia in 1938-39. The 1947 plan for Britain’s granting of independence to the Indian sub-continent was the occasion of widespread violence and killing between the Hindu and Muslim communities; and there is lingering distrust and tension between India and Pakistan, especially in the disputed area of the Frontier Province. Bruce Clark is himself from Northern Ireland which, as he acknowledges “is one of the last places in the western world where conflict rages in the name of religion”. In recent weeks there has been renewed fighting in the long disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh, where the boundaries are unclear between [predominantly Christian] Armenians and Azebaijani Turks who are predominantly Shia Muslims.

Notionally, here in Britain and elsewhere in Europe, the Lausanne principles have been superseded by the Helsinki agreement, signed by 35 European countries [plus America and Canada] in 1975. This agreement insists that countries respect the human and cultural rights of their citizens, including minorities. I am not at all clear how the BREXIT mantra of ‘taking back sovereignty’ affects this principle. When the unspeakable Priti Patel tweets: “After many years of campaigning, I am delighted the Immigration Bill which will end free movement on 31st December has today passed through Parliament”, I think we have the right to be worried. Could we be contemplating a Lausanne-type solution ? Compulsory resettlement of undesirable aliens whose faces don’t fit ?

November 2020