Books, books, books

I’ve read 95 books during this past year, according to my omniscient MacBook. And I may well push on into three figures over the next ten days. It’s nothing to be proud of; Susie complains that I always have my nose in a book. The truth is that, because of a troublesome hip, I have been walking less since the end of the summer. I’ve not walked round Arthur’s Seat since October, preferring in recent weeks to walk lower down in the park alongside the loch towards Duddingston. And my smart attache case of painting things sits reproachfully, unopened in the hall.

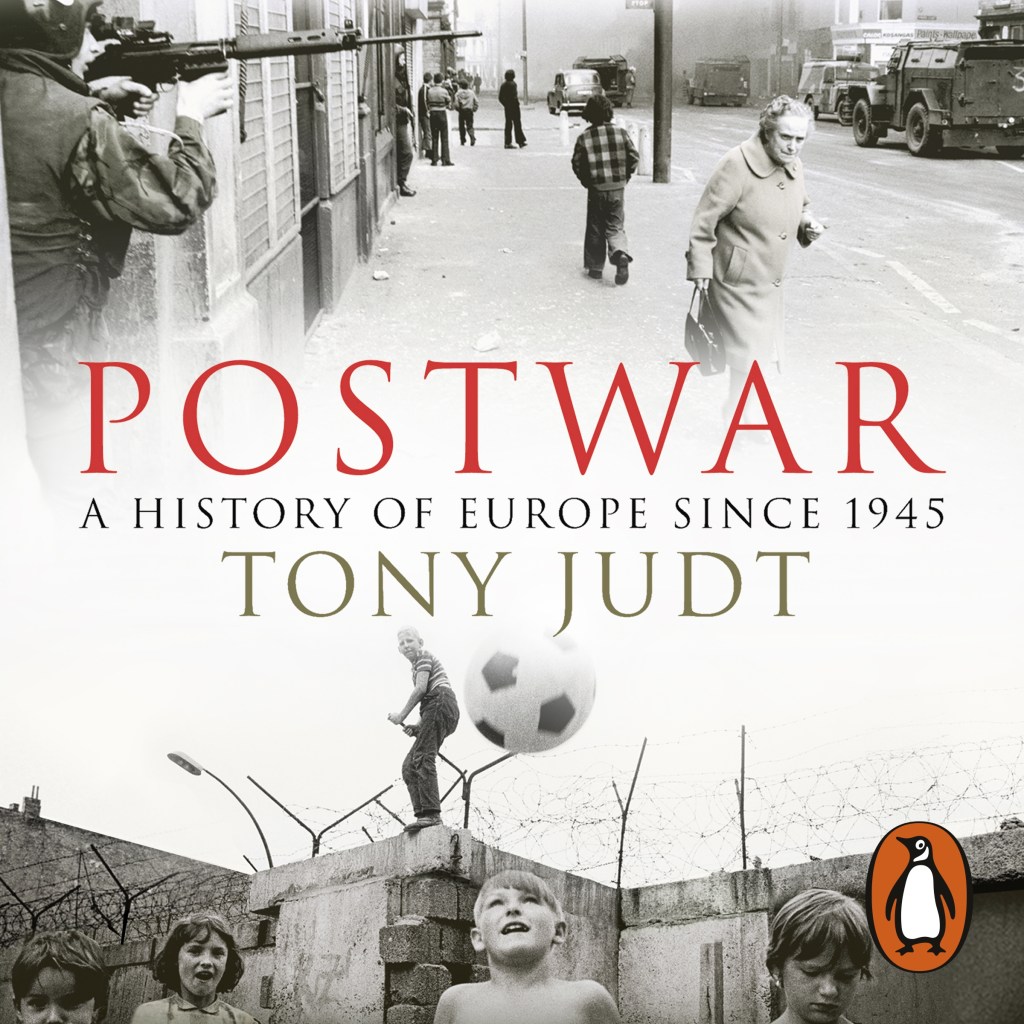

Most of the books I have read this year are either biographies and memoirs, or twentieth century and military history. With a mixed clutch of novels. Some history. And a very little theology.

The disappointments

Roland Chambers’ The Last Englishman was a disappointment early in the year. Arthur Ransome [b.1884] was a strange man: best known as the author of Swallows and Amazons, and a further 11 books in the series published between 1930 and 1947, all set in a pastoral idyll in the Lake District between the wars. Ransome was initially a publisher and jobbing journalist, who from 1913 to 1924 lived and worked in Russia and the Baltic States. He was thus a witness to the Russian Revolution, was on intimate terms with many of the leading Bolsheviks, and married [a second marriage] Trotsky’s secretary. He had close links with MI6, and was suspected of spying by/for both sides. Yet this book, which I found in OXFAM, is a surprisingly dull book.

From the same shop, I found Michael Jago’s John Bingham: The man who was George Smiley. John Bingham [b.1908] was a journalist, a moderately successful novelist, and agent runner for MI5 1940-45 and again 1950-69. In 1960 he became the 7th Baron Clanmorris of Newbrook in County Mayo. He was dumpy, unremarkable, with thick glasses, easily lost in a crowd. He was also a skilled interrogator with strong conservative, ethical principles. From 1958 he was [briefly] a colleague in MI5 of [my hero] John le Carré, and undoubtedly the model for George Smiley. Bingham’s wife, Madeline, hugely resented le Carré’s writing success, while John’s books languished. But John Bingham was more tolerant, while deploring le Carré’s negative presentation of the security service. Again the underlying story is promising, but the book is dull.

From the shelves of the apartment in Grenoble, I read three early books by P.G. Wodehouse. Something Fresh, Summer Lightning, and Heavy Weather, published between 1923 and 1933. I think the Jeeves books are great fun. But these three, slight books, featuring the pig-loving Clarence. 9th Earl of Emsworth, and the eccentric bunch of visitors at Blandings Castle, are mannered and distinctly unfunny. Heavy weather in fact.

My least favourite book of the year was Touching Cloth, a ‘confessional’ memoir by a 30-year-old “priest and writer”, Fergus Butler-Gallie. The focus is on his curacy in a working class parish in the Liverpool Diocese, offering an irreverent take on church life. It won rave reviews in The Times and elsewhere. I found it arch, irritating, and unfunny. He is now Vicar of Charlbury in the Oxford Diocese, a few miles up the road from Woodstock where were lived in the 1970-80s..

Old favourites

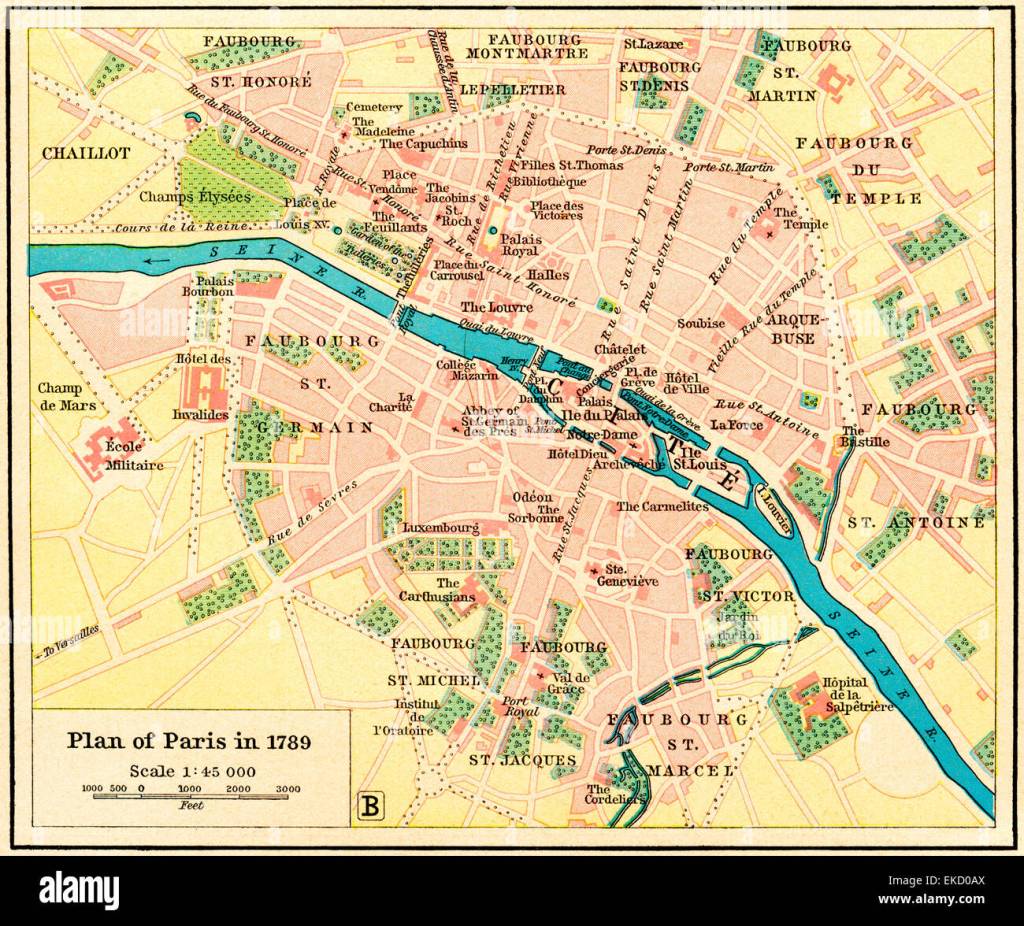

Early on in the year I re-read two early volumes of Arthur Koestler’s memoirs, Arrow in the Blue and Scum of the Earth. These books were published in 1954, and I first came across them in the CH library more than 60 years ago. Arrow in the Blue takes Koestler from a Jewish family background in Budapest to a Technische Hochschule in Vienna, where he was heavily involved in a Zionist Burschenschaften and in Zionist politics. On April 1st, 1926, he set out penniless for Palestine. In September 1927 he became Jerusalem and Middle East correspondent for the Ullstein newspaper group. In 1929 he moved to Paris. Shorty afterwards he transferred to Berlin, and in December 1931 he joined the Communist Party. A fascinating journey across a different world. Scum of the Earth sees Koestler in France in 1940. He is arrested in Paris, and interned with a mish-mash of European anti-Fascists in the interment camp at Le Vernet.

During the summer I spent hours in our summer house turning the pages of Richard Crossman’s three volumes of Diaries of a Cabinet Minister. I met Crossman briefly many years ago, and found him arrogant and difficult. The diaries are exhaustive and exhausting. And sometimes funny.

Now that Archbishops are in the news, I re-read Owen Chadwick’ life of Michael Ramsey, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1961 to 1974. It is an excellent biography. Chadwick traces Ramsey’s life: Repton, Magdalene, Cambridge, and Cuddesdon; parish ministry and Lincoln Theological College, 1928-40; Professor of Theology at Durham and Cambridge, 1940-52; Durham and York, 1952-61; Archbishop of Canterbury 1961-74. He was appointed contrary to Archbishop Fisher’s advice. I also looked again at Michael De-la-Noy’s book on Michael Ramsey. This short [240 pp] sketch by his onetime Press Secretary emphasises Ramsey’s personal qualities; his physical clumsiness; his lack of small talk and social skills; his penchant for long silences. Lots of good anecdotes. He comes across as loveable; prayerful; and completely bonkers !

Not all books in chaplaincy apartments are unrewarding. In Chantilly I found and re-read William Dalrymple’s book From the Holy Mountain. Dalrymple follows in the footsteps of John Moschos, a sixth-century monk, from Mount Athos to Upper Egypt, visiting a variety of Eastern Orthodox congregations; and learning how they have lived with their Jewish and Muslim neighbours. He visits monastic communities in eastern Turkey, Syria, the Lebanon, Israel, and Egypt. They are all suffering from civil war and factional violence. Today the journey would be quite impossible.

Highly recommended

On the recommendation of [Bishop] Richard Holloway I tracked down a copy of Edwardian Excursions: from the Diaries of A.C. Benson. Arthur Benson [1862-1925] was the eldest son of Archbishop Edward Benson and his eccentric wife Minnie. AC Benson was educated at Eton and King’s Cambridge; subsequently taught at Eton, and was a don and then Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge. He knew a huge number of people in late Victorian and Edwardian England; and kept an enormous, unpublished diary of several million words. It is a charming, privileged, rather bitty book. These extracts mainly concern travels in England, by bicycle and cross-country train, between 1898 and 1904. Edited by David Newsome, onetime headmaster of Christ’s Hospital.

In a different world and a different century, I read with great pleasure Rory Stewarts’s Politics on the Edge. Stewart was born in Hong Kong in 1973; educated the Dragon School, Eton, and Balliol. Gap year in the Black Watch in 1991. Foreign Office in Indonesia and Montenegro 1997-2000; sabbatical to walk across Iran and Pakistan, 2000-2002; Iraq and Afghanistan 2003-2008. Academic in the USA, 2008-10. MP for Penrith, 2010-19. At Harvard Michael Ignatieff encourages him to become a doer’, not just a commentator. This is a detailed account of his 10 years in politics, as a Tory back-bencher, minister, and leadership candidate. It is an excoriating account of British [and Tory] politics. He has just failed to become the Chancellor of Oxford University.

For cricket-lovers my most enjoyable read of the year was David Foot’s Beyond Bat and Ball. Foot is a West Country journalist and cricket writer, perhaps best know for his slim life of Harold Gimblett, the fast-scoring Somerset and England opening batsman who took his own life. Beyond Bat and Ball is a beautifully written collection of eleven portraits of [what you might call second rank] cricketers. Including that village cricket enthusiast Siegfried Sassoon, who was a modest performer for and patron of the Heytesbury cricket club, where my grandparents lived latterly.

After our return from Chantilly earlier in the year I read two more of Donna Leon’s Brunetti books. She writes beautifully, and the books are instantly evocative of a city I love. Towards the end of the year I have been re-reading Evelyn Waugh with much pleasure. The early novels are a bit thin. But both Decline and Fall and Scoop have some wonderfully funny scenes.

Looking ahead

By the time we get to January I hope to have finished reading Anne Applebaum: Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe 1944–56. It has been sitting on my shelves since we were in Kyiv, and A.N. Wilson says “It is the finest history book I have read”. But like other books on that part of the world, it is a rather grim read. Roughly in the same part of the world I hope to get round to reading Daniel Finkelstein’s Hitler, Stalin, Mum and Dad, which I was given for my birthday last July. Finkelstein’s father came from Lviv, in western Ukraine, so I guess it will have something in common with Philippe Sands’ wonderful East West Street.

I’m also looking forward to reading Anthony Beevor: The Battle for Spain, which I found in an OXFAM shop in Stockbridge recently. [And maybe looking again at another dozen or so books on the Spanish Civil War.] In the Shelter shop in Stockbridge last week I also found a copy of Richard Holloway’s most recent book [his last, last book !] On Reflection: Looking for Life’s meaning. It’s obviously a suitable title for one’s eightieth year. And I am deriving huge pleasure from A Northern Wind: Britain 1962-65 by cricket lover and social historian David Kynaston. Borrowed from the Fountainhall Road library. Of which more another time. The book, not the library.

Envoi

Christmas is suddenly less than a week away. We were delighted to see Jem here in Edinburgh, sadly on his way to Dougal’s funeral down in Duns. I went down to Duns with him and there were a lot of people in the Parish Church. A sombre occasion. And next week we go across to Fife to meet up with Craig and the girls and some of Craig’s family.

December 2024