A time capsule from the garage

Mayfield Church [shortly to be reborn as Newington Trinity] are having a paperback sale in November. Which encouraged me to ferret around in the garage, where I found a couple of shelves of elderly paperbacks which had never made it onto the bookcases in the house. It is instructive to see what I was reading three and four decades ago. But it is difficult to resist the temptation to re-read all the books before putting them out.

Christopher Isherwood

Christopher Isherwood was a bit of a hero from my late school days. I was fascinated by the intellectual and political life of the Nineteen Thirties. And by the thirties’ intellectuals and writers. It was admittedly all a bit cliquey. Spender admired Auden. And Auden admired Isherwood, his prep school friend. And Isherwood admired his school-friend Edward Upward, the ’Chalmers’ ofLions and Shadows. [It is unnerving to realise that in the sixties, that era was only thirty years ago. The same distance as we are now from the early nineties; John Major as Prime Minister; John Smith as leader of the Labour Party; a massive Lib-Dem by-election win in Newbury; the first high speed train through the Channel Tunnel. It all feels like yesterday !]

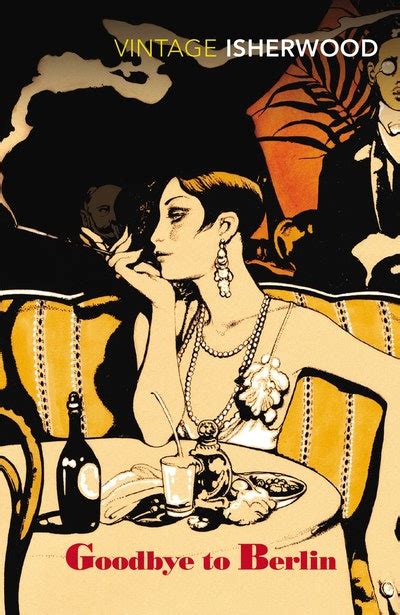

After an unfinished degree at Cambridge, and brief, unhappy spells as a medical student and a private tutor, Isherwood joined his friend Auden in Berlin in 1929. It was the closing years of the Weimar Republic, marked by high unemployment, social unrest, and a simmering tension between the Communist Party and the burgeoning Nazi Party. From 1923 onwards Berlin was characterised as much by its partying and decadent night-life as by economic depression. Wild parties, the cabaret scene, drugs, especially cocaine, deregulated prostitution, male homosexuality, and androgyny all helped to make Berlin a party-lovers’ paradise. This is the background to two of Isherwood best books, Mr Norris changes trains and Goodbye to Berlin. Mr Norris [published in 1933] stems from a chance encounter on a train with the sinister Arthur Norris. His new friend is a man of contradictions: lavish with hospitality, but heavily in debt; excessively polite, but sexually deviant. Norris is a flabby rogue, but personally engaging. Against the background of pre-Hitler Germany he symbolises a society moving towards dissolution. Goodbye to Berlin [published in 1939] continues Isherwood’s picture of that vanished city; scenes range from the tenements and night-bars of the slums to the opulent villas of the very rich, mainly Jewish, families. Isherwood himself is the first-person narrator, working as an impecunious English teacher. Both books, beautifully written, were originally intended as part of a bigger, panoramic novel The Damned. Which remained unwritten. Goodbye to Berlin introduces us to Sally Bowles. Her story was the basis for the New York stage play I am a camera, which later morphed into the musical Cabaret.

Lions and Shadows [published in 1938] is a thinly fictionalised autobiography. It is the story of a writer finding his literary feet; tells of holidays on the Isle of Wight; and records his relationships with the thinly fictionalised W.H. Auden and Edward Upward. I like the book less now than I did when I first came across it. It was followed by Prater Violet [published 1945], an extended portrait of Isherwood’s working with the imperious, charismatic Austrian film director Friedrich Bergman. As they work on a frothy story set in nineteenth-century Vienna, Hitler annexes the real world Vienna, where Bergmann’s family are at risk.

I was less interested when Isherwood and Auden emigrated to the States in January 1939, After which Isherwood became increasingly involved with Vedanta, a Hindu form of philosophy and meditation, to which he had been introduced by Gerard Heard. But if time allows before the November book sale, I shall look again at Down there on a visit [published in 1962], an extended account of his travels around Europe with his young German boy-friend, Heinz, with whom he had left Berlin in 1933. And then, time permitting, at A Single Man [published in 1964], hailed by some critics as Isherwood’s best novel. I guess the truth is that most of his work is autobiographical, and that after he left Berlin I lost interest.

The Flashman books

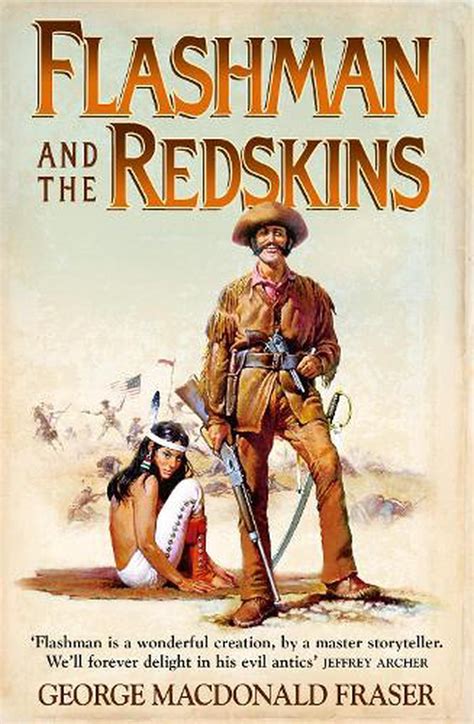

On a very different plane, a shelf of Flashman books are also heading for the sale. George Macdonald Fraser [b.1925] was a Scottish novelist and screen-writer. After leaving school in 1943, he served as a junior officer in the Burma campaign. His account of his time in Burma, Quartered Safe Out Here, published in 1993, is one of the minor classics of the literature of the Second World War. In the 1960s he embarked on his series of Flashman books. These purport to be the memories of the nonagenarian Sir Harry Flashman, V.C., the fictional bully and coward of Thomas Hughes’ Tom Brown’s Schooldays. He is an endearing rotter.After leaving Rugby in disgrace, Flashman fought his way around the world in the British Army, serving in virtually all of [what one writer calls] ‘Queen Victoria’s little wars’, displaying a high degree of funk in the face of danger and a willingness to bed every woman he encountered. The books drew admiring reviews, and were notable for their historical accuracy and the detail supplied in the historical footnotes.

I’ve been enjoyably re-reading Flashman and the Redskins [first published in 1982]. It is the seventh of the series, set partly in 1849-50 and then again in 1875-76. Flashman is trapped in New Orleans after crossing the Atlantic on a slave-ship, the Balliol College, owned by his father-in-law, John Morrison of Paisley. He is given shelter by a susceptible English matron, Susie Willinck, who runs a New Orleans bawdy house. Susie decides to relocate, and Flashman, travelling as Captain Beauchamp Comber, R.N., is the military escort to her harem as they join the crowds of Forty-Niners travelling westwards from Kansas City into what was then the great unknown of the Far West. In the course of his adventures, Flashman marries both his employer, Susie Willinck, and then the Apache princess Sonsee-array, fourth and favourite daughter of Chief Mangas Colorado. The Yawner, later known as Geronimo, is their best man.

On a return visit to the States some twenty years later, the Sioux chief Spotted Tail takes a shine to the flirtatious Elspeth [née Morrison]. And Flashman is inveigled by the seductive Mrs Arthur B. Candy into making an inspection for the Upper Missouri Development Corporation. A trip that takes him up into the badlands of North Dakota, where he is one of the few survivors of Custer’s disastrous sally at the Battle of Little Bighorn. Partially scalped on the battlefield Flashman is rescued by the mysterious half-Indian scout Frank Grouard. It’s all clean-ish good fun.

I wonder when boys stopped playing Cowboys and Indians. Presumably at least a generation ago, maybe two. When I was just six, I spent a couple of months living with my grandparents in Minety, in Wiltshire, where my grandfather was the station-master. I don’t remember much about it. But someone whom I only knew as ‘Old Man Meakin’ lent me a book about the Wild West and about Red Indians [presumably no longer permissible usage]. And it was said hat he had been out there in his youth, and had met people who are now just names like Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill. That was about seventy years ago. And there’s no-one alive with whom I could check the story.

Here we go again

The rugby world cup has been a bit of a disappointment. It’s been going a month; we still haven’t reached the quarter-finals, there have been two good games so far [France v. New Zealand, and Ireland v. South Africa], and the best four teams in the world are all in the same half of the draw. England have reverted to [unattractive] type under Steve Borthwick [Baldrick]. Might the best Scotland team for a generation be in with a chance against Ireland tomorrow ?

I walked along the river Tyne from East Linton to Haddington the other day, a bit over six miles. At the end I nearly got stuck in the cemetery at Haddington. But I suppose that happens to people of my age ! And Susie and I met up for lunch in The Loft, one of my favourite cafes. They do an excellent Ploughman’s Lunch, and there was enough to bring the rest home for tea.

I can’t bear to write about the political scene. The Tory Party conference shows us that the Conservative Party is morphing into an unattractive bunch of UKIP-style, xenophobic, self-serving, English nationalists. All demanding that we lock up immigrants. And tax cuts. It was dreadful seeing the gormless Liz Truss reappear the other day, still peddling the Trussonomics which precipitated a financial collapse a year ago. But possibly even worse the video clip of Pritti Patel and Nigel Farage dancing together to Sinatra’s I can’t keep my eyes off you. Crumbs ! I see that Rishi Sunak’s new slogan is Action not words. Which he has followed up by writing a letter to The Times [co-written with Signora Water Melon] asking why people aren’t doing anything about the migrant problem. You couldn’t make it up.

I’m leaving the country soon …

October 2023