Confession

Confession is said to be good for the soul. So I must start by confessing that, although Susie and I lived in the 14ème arrondissement in Paris back in the 1970s, I never visited the Musée de la Libération at Denfert-Rochereau. And, more reprehensibly, although Susie and I later lived in Lyon for thirteen years, I never, ever visited Place Castellane up in Caluire. It was here, on the corner of the square, in a house belonging to Dr Frédèric Dugoujon, that ‘Max’ was arrested in June 1943. ‘Max’ was of the cover names of Jean Moulin, a Prefet suspended on half-pay by the Vichy government, who had been named by General de Gaulle as the political head of the Resistance. The circumstances of his arrest are enigmatic. Who was it that betrayed him to the Gestapo ? At the time of his arrest Jean Moulin was a little known figure. But for complex reasons he has been retrospectively anointed as France’s greatest hero of the Second World War.

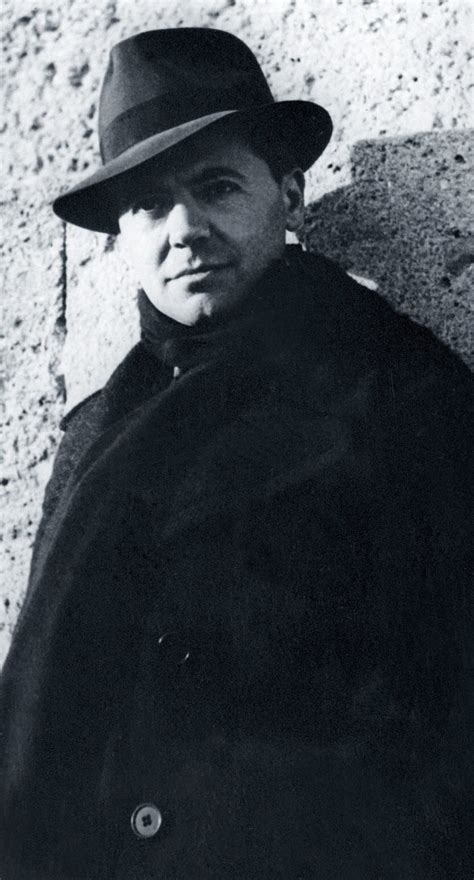

I have been reading Army of the Night by Patrick Marnham, a gripping and detailed account of the life of Jean Moulin. Marnham himself has a CV of which I am mildly envious: after Oxford he became a reporter on Private Eye, wrote for a variety of newspapers including The Times, and The Guardian, became literary editor of The Spectator, and was the first Paris correspondent of The Independent. He now lives [in retirement] in Woodstock, in Oxfordshire. Where we lived in the 1980s.

The making of Jean Moulin

Moulin was born in 1898, in the very dull town of Beziers, in the south of France. His father, Antonin, was a republican, anti-clerical schoolmaster, who taught French history and literature in the same classroom for fifty years. The young Jean was a rebellious student, but in 1921 took a law degree at Montpellier. He promptly joined the corps préfectoral, and rose swiftly through the ranks becoming in 1925, at the age of twenty-six, the youngest sub-prefect in France, at Albertville in Savoy. The following year he married Marguerite Cerruti, a professional singer from Paris, described by his sister Laure as “pretty but a bit fat”. The marriage lasted a little over a year. In January 1930 Moulin was transferred to Chateaulin in Brittany. It was a dull posting from which he was rescued in 1933 by Pierre Cot, the dynamic and ambitious young government minister. Cot was an excellent public speaker who valued Moulin’s administrative skill and application. Aged thirty-four, Moulin was a successful young administrator, a divorcé with a crowded social life; notionally neutral in party political terms, but anti-monarchist, anti-clerical, and probably a freemason. For the remainder of the 1930s, the careers of Pierre Cot and Jean Moulin ebbed and flowed as successive French governments came and went. In March 1937, at the height of the Spanish Civil War, Moulin was nominated Prefect of the Aveyron, becoming at thirty-seven the youngest prefect in France.

In September 1939, with the signing of the Nazi Soviet Pact, all the hopes of Moulin and Pierre Cot, and of the anti-fascist Front Populaire collapsed. When the Germans invaded France in the summer of 1940, Jean Moulin was behind his desk in Chartres, to where he had transferred the previous year. It was not a promotion, but it was an advantage to be much closer to Paris

The War

In June 1940 Moulin ignored an order to abandon Chartres. When the city was surrendered to the Germans, he was arrested and beaten up for refusing to sign a document that incriminated French troops. He decided he could take no more beatings and cut his throat with a piece of broken glass. But he was rescued by a guard and the wound slowly healed. Was it a suicide bid ? Or an attempt to engineer an escape ? Marnham is happy to sit on the fence on this question.

In November 1940 Moulin was relieved of his post and began to build a new life. He returned to St. Andiol, the family home, in unoccupied France, and busied himself with his two mistresses and with opening an art gallery. It is perhaps surprising that over the coming months Moulin made very little attempt to associate himself with the growing movements of Resistance in the Vichy zone. He lived quietly as Joseph Mercier, holder of a false passport and a false exit permit, for almost a year. And then in September 1941 he left to travel via Spain and Portugal to London. It was only the third time in his life that Jean Moulin had left France. Ski trips to the Tyrol and a weekend in London were his only previous trips abroad. In London he threw in his lot with the head of the Free French, Brigadier-General Charles de Gaulle; a man nine years older than Moulin, but whose rank in the republican hierarchy was inferior [a Prefet counts in rank as a Major-General]. De Gaulle was impressed by Moulin’s rank and by his experience; in 1941 de Gaulle was dangerously isolated and many well qualified French exiles [such as Jean Monet and Raymond Aron] had turned their backs on him

The arrest of Jean Moulin

In January 1942 Moulin was parachuted back into France. Armed with a document from de Gaulle giving him plenipotentiary powers, his task was to unite the disparate strands of the French resistance. His only assets were money [which the resisters needed urgently] and regular liaison with London. There now began a year-long struggle between Moulin and the three principal leaders of the southern resistance groups, Henri Frenay of Combat, Emmanuel d’Astier de la Vigerie of Libération, and Jean-Pierre Levy of Francs-Tireur. For the last year of his life, Moulin sought to unite and direct their competing interests and explosive personalities, while being pursued by both Vichy and the Gestapo. His mission was both to dissolve the Resistance as it existed in January 1942, and to remould it as an instrument to serve de Gaulle’s project for the liberation of France.

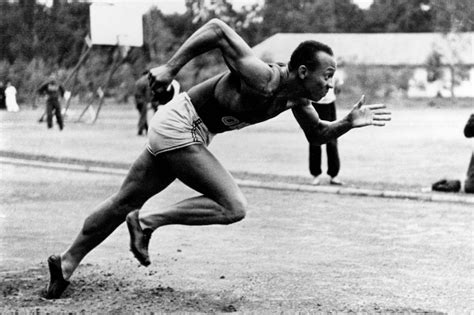

By June 1943 it seems that Jean Moulin had reached the end of his strength. He habitually wore dark glasses, hardly a disguise, a brown trilby, and a scarf to hide the distinctive scar on his throat. By now he was heartily disliked by many resisters in France; seen by some as the agent of a potential Gaullist military dictatorship, by others as a crypto-communist .On June 9th General Delestraint, named as military commander of the Secret Army, was arrested in Paris. On June 21st, Moulin now code-named ‘Max’ was arrested with six other Resistance leaders at the house of Dr Dugoujon in Caluire. One of the seven René Hardy of Combat escaped from custody. [After the war Hardy was twice tried on suspicion of betraying Jean Moulin, and was twice acquitted.] All those who were arrested were interrogated and beaten up in custody. Nobody knows when and where, and how, Jean Moulin died. He was last seen alive in France in June. But his dead body was formally identified in Germany, in Frankfurt, two weeks later. It is widely believed that, having refused to talk to his captors, he was beaten into a coma on the orders of the senior Gestapo officer in Lyon, Klaus Barbie. [Subsequently protected by none other than François Mitterand.] And that he died a hero.

The resurrection of Jean Moulin

In December 1964 the ashes of Jean Moulin were transferred to the Panthéon, the resting place of heroes of the Republic. [And a symbol of republican anti-clericalism.] The move was proposed by the socialist parliamentary opposition, who wanted to underline on the twentieth anniversary of Moulin’s death, under the presidency of Charles de Gaulle, that the left had played an important part in the Resistance. But de Gaulle himself adroitly postponed the ceremony until the twentieth anniversary of the liberation; and, taking his place centre-stage in military uniform. demonstrated his own role as the living embodiment of wartime victory. While enjoying left-wing support.

Tribute to Moulin was paid by the writer and politician André Malraux. “Crouched over the microphone with wild eyes and a beaky nose”, writes Marnham, “he resembled an elderly vulture”. In a powerful address, Malraux evoked the spirit of what the Resistance [wanted to believe it] had been. “Think of his poor battered face, of those lips which never spoke. That day, his last day, it was the face of France.” It didn’t seem to matter that the coffin was virtually empty. And that Moulin’s body had never been found. Jean Moulin was resurrected from wartime obscurity and became, through Malraux’s oratory, the personification of the Resistance, and the Resistance became the emblem of the whole of France.

It’s a good story. And a good book.

Envoi

We are two weeks back from Ankara. We enjoyed being there, and were warmly greeted by the small but welcoming congregation. On our final Sunday in Lyon, Susie and I were pleased to attend the Coronation Garden Party at the British Embassy. And I had the privilege of being one of the judges of the Scone Baking competition. Something for which theological college never prepared me.

Since we have been home we have attended three church fund-raising events: first, St Peter’s [Lutton Place] summer fete last weekend; followed by a garden opening in Murrayfield in support of St Salvador’s, Stenhouse, with music from No Strings Attached, Susie’s band; and then a coffee morning for Christian Aid at Priestfield yesterday. On Tuesday we go south to High Wycombe and Watlington. From next weekend we shall be in Normandy for a week, at Barneville-Carteret, with the children and grand-children. It will be strange being there without Joanna. But she will be much in our thoughts and in our conversations.

May 2023