I’m ambivalent about mountains. On the one hand I’m very acrophobic around bridges, high buildings, and mountain roads: as a child I baulked at going up the Monument in London, more recently I used to be nervous about driving across the Forth Road Bridge, and driving over the Viaduct de Millau is the stuff of nightmares. When I drove from Lyon to Geneva two decades ago, with a long stretch of elevated motorway, my hands had to be prised off the steering wheel when we arrived in Geneva. Visiting the Grand Canyon in 2016 made my toes curl.

Viaduc de Millau

On the other hand I like looking at mountains. ICS conferences at Beatenberg with recurrent views of the Jungfrau were a pleasure, once I had negotiated the rather scary busy ride up from Interlaken. Sitting in Grenoble a year ago, with snow-capped mountains at the end of every street and in every direction, was a delight. And, somewhat perversely, I enjoy books about mountains. Think Nan Shepherd and Robert Macfarlane. And books about mountaineering.

Grenoble 2024

Wade Davis: Into the Silence

This book has sat unread on my shelves upstairs for several years. Wade Davis is a Canadian anthropologist, a writer and photographer, with a string of books to his name. Into the Silence, subtitled The Great War, Mallory, and the Conquest of Everest, is an ambitious and prodigiously researched account of the three Everest expeditions of the 1920s. The unifying thread is the person of George Mallory “the scatter-brained Adonis and Bloomsbury favourite whose fate would enthral the nation” [John Keay in The Literary Review].

Davis gives us the historical background. Although Britain had ruled [and transformed] India, very little was known of the mountains to the north. Tibet was uncharted and unknown. Only three Europeans had visited Lhasa between 1750 and 1900. Britain had no territorial designs on Tibet. But Curzon authorised [what was in effect] an invasion of the country in 1903-04 in order to establish diplomatic relations and to resolve a border dispute between Tibet and Sikkim, a British protectorate. Younghusband’s mission was a complete military success and forbade Tibet to have any relations with other foreign powers. After opening up the road to Lhasa Younghusband authorised two great thrusts of exploration into the whole mountainous wilderness between Tibet and Nepal. From one of these expeditions came the first clear photographs of the snowy summits of Makalu, Chomo Lonzo, and Everest. “Towering up thousands of feet”, wrote Captain Cecil Rawlings of Everest, “a giant among pygmies, and remarkable not only on account of its height, but for its perfect form. No other peaks lie near or threaten is supremacy : : It is difficult to give an idea of its stupendous height, its dazzling whiteness and overpowering size, for there is nothing in the world to compare with it”.

As early as 1912 questions were being asked as to why the summit of Everest had yet to be conquered. In the previous century, it was noted, more than £25 million had been spent on the fruitless quest for the North Pole. Four hundred men had died, and two hundred ships had been lost. But there had been no serious attempt on Everest. No European had reached its base. The immediate surrounds of the mountain remained uncharted. Little was understood of its structure, the character of its snow and ice, its topography, or the nature of its rock formations that made up its imposing bulk and which narrowed into its imposing ridges.

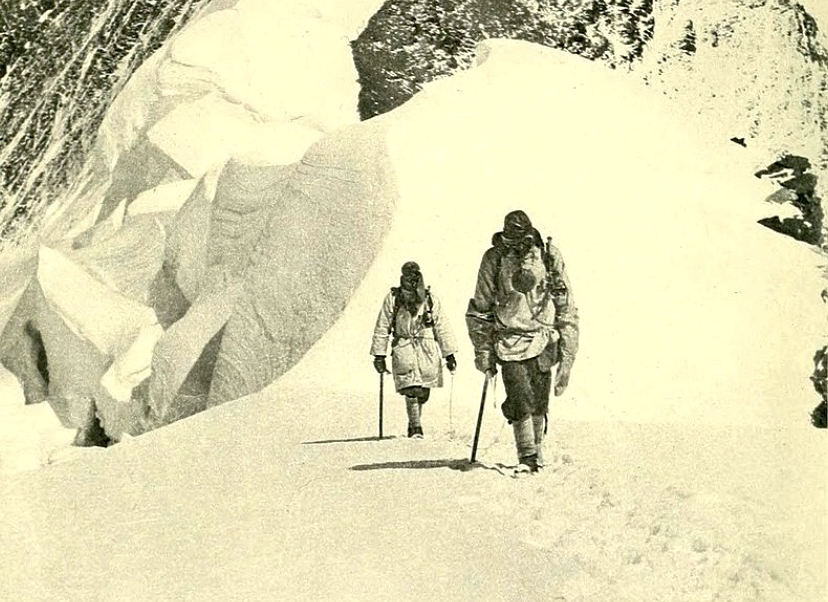

Descending, 1922

The Everest expeditions of the 1920s

Shortly after the end of the 1914-18 war, Sir Thomas Hungerford Holdich, President of the Royal Geographical Society was urging the government to consider the possibilities of launching an Everest expedition. In January 1921 the Mount Everest Committee came into being, sponsored by the Royal Geographical Society and the Alpine Club. The RGS was primarily interested in mapping the largely unknown surrounding area; the Alpine Club in the climb itself.

The committee was very much an imperial body, and the members of the expeditions that followed were primarily military men. As Wade Davis explores in considerable detail, many of the expedition’s personnel were scarred, psychologically if not physically, by their experience in the Great War. The leader of the 1921 Reconnaissance Expedition was Colonel Charles Howard-Bury, a wealthy Old Etonian aristocrat, a fighting soldier mentioned in dispatches seven times and the holder of every medal for valour short of the Victoria Cross. Howard-Bury had survived four years on the Western Front, at Ypres, on the Somme, and at Arras; and ended the war as a German prisoner-of-war in a camp at Clausthal in the Harz mountains. The expedition doctor and naturalist was Alexander Wollaston, who in 1914 had [aged 39] volunteered as surgeon on an armed merchant cruiser in the North Sea; and who subsequently fought in the bloody but little-known campaign in German East Africa. Another early recruit was Dr Alexander Kellas, an Aberdonian and a specialist in physiology with an impressive track record of Himalayan expeditions. Kellas should never have been considered, at 53 was simply too old for Everest, and would die in Tibet.

Colonel Charles Howard-Bury

When after the Reconnaissance Expedition Howard-Bury was unavailable, leadership of the 1922 and 1924 expeditions passed to General Charles Bruce, an Old Harrovian and career soldier, who had commanded a Gurkha battalion at Gallipoli where he was severely wounded. Bruce was good-humoured, said to be an excellent raconteur and fount of bawdy stories. He had experience in the Himalayas and was in 1923 President of the Alpine Club. But his age [he was 56 in 1922], his health record, and his high blood pressure raised questions about his appointment. Bruce’s leadership of the 1922 expedition was generally admired, and he was reappointed in 1924. But in the latter year he contracted malaria while tiger shooting before the expedition and had to be stretchered out of Tibet, the leadership passing to his deputy, Major Edward Felix [Teddy] Norton. Another career soldier, an Old Carthusian, who had survived four years on the Western Front, fighting on the Marne, at Ypres, Loos, the Somme, and Arras, and then surviving the great German Spring Offensive of 1918 when he was at Bapaume.

General Charles Bruce

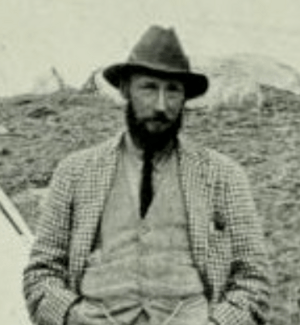

George Mallory

They weren’t all military men. George Mallory, the finest rock climber of his generation to survive the war, was an obvious candidate for Everest. Mallory was the eldest son of an Anglican vicar, who won a maths scholarship [aged 13] at Winchester in 1900. He loved everything about Winchester: “the games at which he excelled, the spirit of ardent patriotism, the value placed on honour, loyalty, sportsmanship, and duty, the prayers and hymns, and the rousing renditions of the national anthem that summoned the boys to higher imperial challenges”. At Cambridge Mallory entered a cloistered world, monastic in its ideals, in Arthur Benson’s words “a place of books, music and beautiful young men”. In the homo-erotic world of the Cambridge of that time the good-looking Mallory [“the heavily lashed, thoughtful eyes … reminiscent of a Botticelli Madonna” according to one obituary notice] attracted an enormous amount of attention. At Cambridge he was pursued by the fraternity of the Apostles, among others by Rupert Brooke and Geoffrey Keynes, James and Lytton Strachey, Duncan Grant, Eddie Marsh, and E.M. Forster. Arthur Benson, the son of an Archbishop of Canterbury, tormented scholar and prolific writer, who had been sacked from teaching at Eton under scandalous circumstances, became Mallory’s tutor at Magdalene. Mallory’s passion for climbing was strengthened at Cambridge by his involvement with the Cambridge University Mountaineering Club, a group that clustered around Geoffrey Young, the most prominent climber of the pre-War years. [Young like Benson had been sacked from Eton for indiscretions.]

George Mallory

From 1910 Mallory taught at Charterhouse, a job for which he was ill-suited. In late 1915, now married with a small daughter, Mallory was given leave to join up and was given a commission in the Royal Artillery. He survived the fighting on the Somme and was spared from Passchendaele by a broken foot from a motor-cycle accident. When he returned after the war Charterhouse had become intolerable. Geoffrey Young proposed Mallory to the Everest Committee, as a route out of school-mastering onto a bigger stage. And Mallory in spite of his wife Ruth and young children was irresistibly attracted to the cause of Everest. It seemed like a good career move.

George Finch

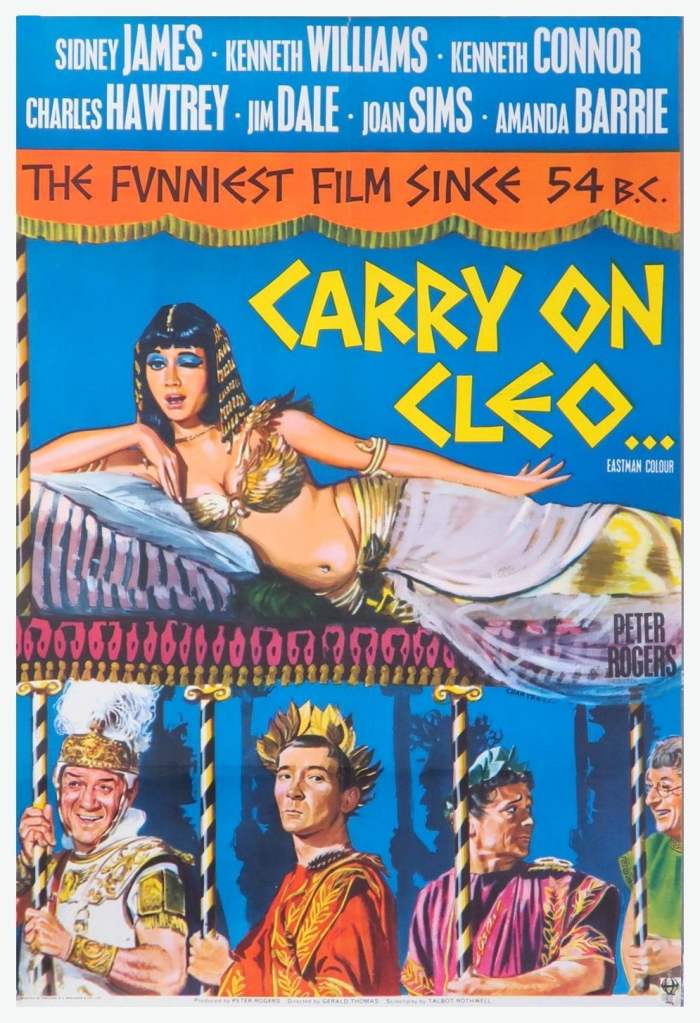

If Mallory was Britain’s finest rock climber in 1921, the finest climber on snow and ice was thought to be George Finch, an Australian from an unorthodox family background. Finch had studied in Paris and then in Switzerland, and had earned a strong reputation in the Alps in the years before the war. During the war Finch had served in France and in Egypt with the Royal Artillery, and then in Salonica with the Royal Army Ordnance Corps. For his work in Macedonia Finch was awarded the MBE. Where British climbers still wore Norfolk tweed jackets, Finch designed and produced a windproof anorak and then the first down coat. Finch and Mallory had met in Wales at Pen y Pass in 1912, and in 1920 they climbed together in the Alps. In marked contrast to most of his fellow climbers, Finch was an expert in and an enthusiast for supplementary oxygen, working with academics at Oxford University on the design of high-level Primus stoves and bottled oxygen cylinders. In 1921 Finch had a complicated personal life. In June 1915 he had contracted a highly unsuitable marriage to an aspiring actress in Portsmouth. In his absence overseas his wife had a baby boy, fathered by the landlady’s brother, to whom Finch gave his own name. [This was the subsequent Australian actor, Peter Finch.] In 1920 he married again, but this too was very short-lived. In December 1921 he was divorced a second time, and within two weeks married his third wife, Agnes Johnston, a woman who remained by his side for the rest of his life.

George Finch

For the 1921 expedition Finch was initially chosen, but then dropped at the last moment under controversial circumstances following a dubious Harley Street medical review process. Finch was returned to the team for 1922, performed well, and climbed the North Ridge and North Face to a height of 8,320 metres with Geoffrey Bruce, both using oxygen for the first time. But Finch was then dropped again in 1924, officially following a dispute over the reproduction rights of Everest photographs, but seemingly more for being a vulgar Australian and an outsider.

What the expeditions achieved

Nepal was closed to climbers, so these early expeditions all approached Everest from the north through Tibet. None of the expeditions succeeded in reaching the summit. For the 1921 Reconnaissance Expedition Mallory and Guy Bullock and Edward Wheeler all reached the North Col, at about 7,020 metres, before being forced back by strong winds. Mallory thought that the North East ridge looked feasible for a fresher party. The following year Mallory and Lieutenant Colonel Edward Strutt climbed to above 8,000 metres on the North Ridge before being forced back. And the following day George Finch and Geoffrey Bruce, both using oxygen, climbed to 8,320 metres before turning back. These four were the first to climb above 8,000 metres.

The 1922 expedition

In 1924 Norton and Somervell, climbing without oxygen, reached a height of 8,573 metres before being forced back. Four days later Mallory and Andrew Irvine left their high level camp for a further summit bid, using the oxygen apparatus that Irvine had modified. They were last seen by another climber, Noel Odell, apparently approaching the summit pyramid and attempting to climb the very difficult Second Step. They were never seen again.

The 1924 expedition

The disappearance of Mallory and Irvine has spawned a sizeable library of books. Some people think they might have reached the summit, others are sure that they did not. [For both climbers, and especially for the novice climber Irvine, the Second Step would have been a major challenge. Mallory’s body was uncovered decades later, but the evidence as to what had happened is unclear.] Wade Davis is not really interested in whether they reached the summit. He is more concerned to ask what it was that kept the climbers moving onwards and upwards to an almost certain death. He suggests that Mallory had become obsessed by the mountain, and makes a comparison with Captain Ahab and the great white whale. And he argues that for Mallory, and for the majority of members of those early expeditions, their experience of the Great War had given them a familiar [and somewhat casual] attitude towards death. Norton wrote later, “From the first we accepted the loss of our comrades in that rational spirit which we all our generation had learnt in the Great War … the tragedy was very near. As so constantly in the war … Death had taken its toll from the best.”

Envoi

It is a big book [560 pages] and a big read. ‘Majestic’, said Michael Palin. The winner of the Samuel Johnson prize for Non-Fiction in 2012. Though Jim Perrin suggests somewhere that the book is most admired by those who know least about mountaineering. Which includes me.

The photos of the climbers, totally inadequately clothed and equipped by modern standards, are wonderfully evocative. The expedition members look “like a Connemara picnic caught in a snow storm”, said George Bernard Shaw. I find it impossible not to admire the sheer pig-headed courage of these men in the days long before risk assessment and Health and Safety. But at the same time a phrase of Bertrand Russell’s comes to mind, I think from his book on Education and the Social Order; to the effect that the English public schools produced men whose bravery was only matched by their stupidity. Of never wanting to lose face in front of your peers.

Arthur’s Seat from Prestonfield House

The nearest I’ll get to mountains in the near future is looking at Arthur’s Seat from the back garden.

April 2025