A day out in Amiens

Amiens is the biggest city in France that I have never visited. At least not until today. And the cathedral is [said to be] the biggest in France. So, although I had promised myself a trip to the coast, possibly to Dieppe or up to Ostend, I had a more modest day outing to Amiens. Which involved setting my alarm on a very frosty [-5º overnight] morning. And a walk down to the station in glorious sunshine across the race-course.

French railways are currently hit by strikes over Macron’s new pension plans. But trains seemed to running normally. It is just over an hour to Amiens on the train from Chantilly.I like the two storey carriages in France, even on a humble TER. The upper compartment was nearly full, with a significant number of black Africans, who may or may not have been refugees, who mostly got out at Creil. One African opposite me was sound asleep; when the ticket collector woke him up it transpired out that he had missed his stop. And also that he had no ticket.

The cathedral

Amiens has a long pedestrian street leading from the railway station towards the centre of town. It is architecturally undistinguished with a predictable collection of shops, Hema, Jeff de Bruges etc. Nothing prepares you for a first glimpse of the Notre Dame cathedral. It is enormous, 145 metres long, and said to be the biggest church in France. It is essentially a 13th century church, built between 1220 and 1269 in the [high] Gothic style. The interior of the church includes two 13th century recumbent statues of former bishops; a 13th century labyrinth, engraved with the names of the architects; and some very elaborate 16th century choir stalls and choir screens. But the main impression of the interior is the height of the roof and the height-width ratio of the central aisle;

The use of such features as external supporting systems, cross vaults and arches, and external buttresses allowed Gothic buildings to reach huge heights. During the great cathedral building era, builders competed to achieve the highest vaults: at Laon they are 24 metres above the ground, in Paris they are 33.5 metres, at Reims they reach 38 metres, and here in Amiens they reach 41.2 metres. The only higher cathedral vault is St Peter’s at Beauvais, just up the road from here, at 48 metres, which was never completed.

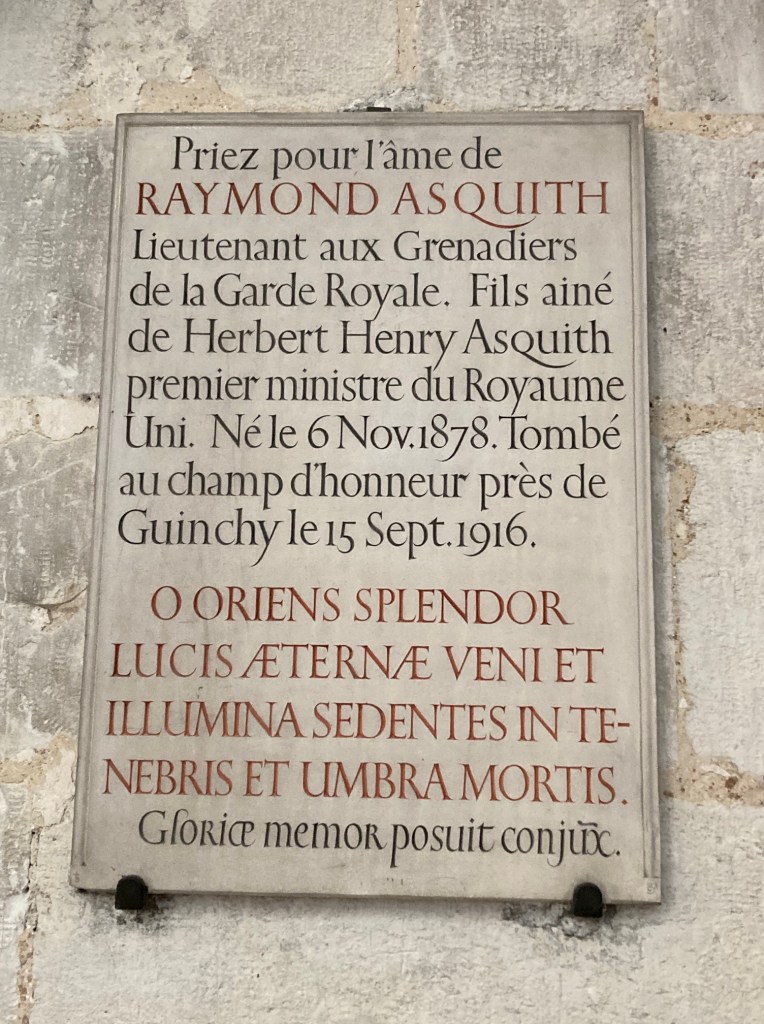

In the cathedral at Amiens I was surprised to come across a wall tablet commemorating Raymond Asquith, who was killed at nearby Guinchy in September 1916. He was the eldest son of the Prime Minister, H.H. Asquith, a distinguished scholar at Winchester and Balliol, a barrister, and the leader of an Edwardian group of socialites and intellectuals known as La Coterie. Raymond Asquith was an officer in the Grenadier Guards, who was shot in the chest at Guinchy and buried at Guillemont. Winston Churchill later wrote in an obituary of him:

“It seemed quite easy for Raymond Asquith, when the time came, to face death and to die. When I saw him at the Front he seemed to move through the cold, squalor and peril of the winter trenches as if he were above and immune from the common ills of the flesh, a being clad in polished armour, entirely undisturbed, presumably invulnerable. The War which found the measure of so many, never got to the bottom of him, and when the Grenadiers strode into the crash and thunder of the Somme, he went to his fate cool, poised, resolute, matter of fact, debonair. And well we know that his father, then bearing the supreme burden of the State, would proudly have marched at his side”

Raymond Asquith was a very superior person. But, I suspect, more admired than liked.

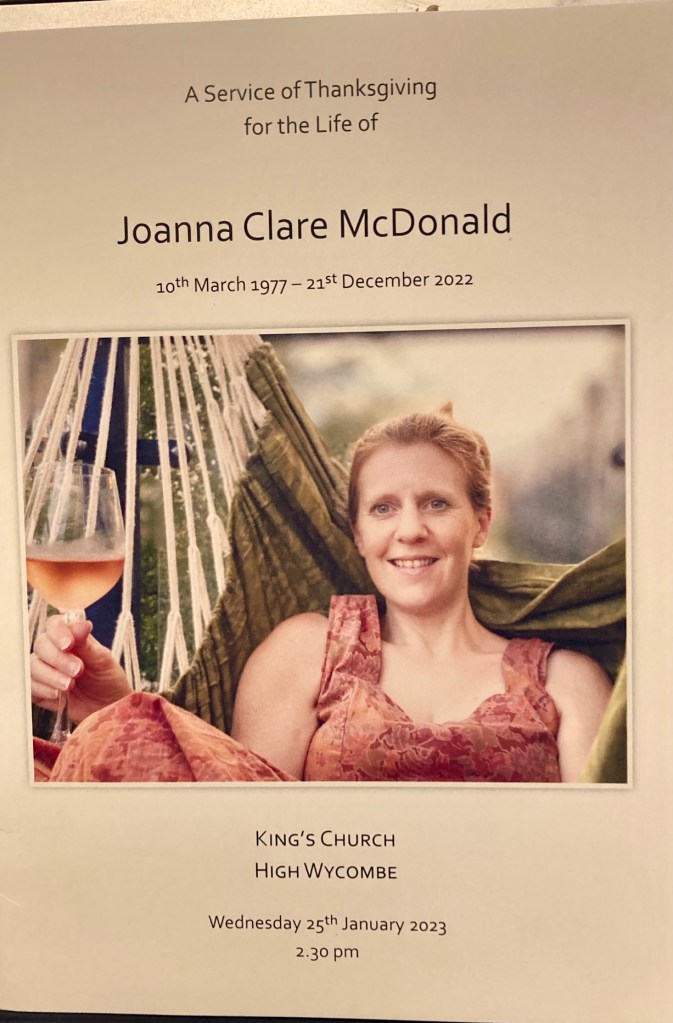

Before I left the cathedral I lit a candle for Joanna. It’s not something that I can remember doing before. But I know that other people have been lighting candles for her. And it seemed like the right thing to do.

Les Hortillonages

The tourist office is close to the west front of the cathedral. Three helpful young people behind a desk, but no other tourists. One of the three gave me a city plan, highlighting the areas I should try to see, while his colleague sold me a couple of postcards.

One of the distinctive features of Amiens is Les Hortillonages, an extensive area of water gardens and market gardens. There are said to be 300 hectares of these gardens and more than 60 kilometres of rieux, or water channels. [Amiens like other places, including Birmingham and Bruges, was once known as ‘the Venice of the north’.] Once upon a time this was where the townspeople grew vegetables, which formed the basis of the reputed Hortillonages soup. And apparently there is still a Saturday morning vegetable market in the Saint Leu district.

My tourist office plan was a bit lacking in detail. But I walked for a mile or so along the Chemin de Halage beside the river Somme. There are a random collection of houses and cottages set back from the river bank, each approached via its own gated bridge over a subsidiary bit of the river. No two bridges are the same. Car access is for riverains only. There are occasional house boats moored, and some impressive willow trees. Apart from occasionally joggers the road was very quiet. It was a bit like walking alongside the Thames from Binsey towards The Trout.

Returning by the same route there are good views of Amiens across the river, with the cathedral and the [hideously ugly] Tour Perret, France’s first skyscraper, dominating the skyline. This tower, built in early modernist style, was the first 100-plus metre tower in France. It was designed by Auguste Perret as part of a post-war reconstruction project. And sits close to the railway station.

Envoi

I had a decent lunch in a restaurant on the Quai Bélu with a view of both the river and the cathedral. In the strong winter sunshine. Up until now I have always imagined Amiens as a rather grey, dour, mist-shrouded city. An image that I may have gleaned from Sebastian Faulks’ Birdsong. In truth the sun may not shine there very often. But it was an excellent day out. If and when I go again, I hope to see something of the Jules Verne quarter and possibly venture into the Musée de Picardie.

February 2023